5 Inference for categorical data

Statistical inference is primarily concerned with understanding and quantifying the uncertainty of parameter estimates—that is, how variable is a sample statistic from sample to sample? While the equations and details change depending on the setting, the foundations for inference are the same throughout all of statistics. We will begin this chapter with a discussion of the foundations of inference, and introduce the two primary vehicles of inference: the hypothesis test and confidence interval.

The rest of this chapter focuses on statistical inference for categorical data. The two data structures we detail are:

- one binary variable, summarized using a single proportion, and

- two binary variables, summarized using a difference (or ratio) of two proportions.

We will also introduce a new important mathematical model, the normal distribution (as the foundation for the \(z\)-test).

Throughout the book so far, you have worked with data in a variety of contexts. You have learned how to summarize and visualize the data as well as how to visualize multiple variables at the same time. Sometimes the data set at hand represents the entire research question. But more often than not, the data have been collected to answer a research question about a larger group of which the data are a (hopefully) representative subset.

You may agree that there is almost always variability in data (one data set will not be identical to a second data set even if they are both collected from the same population using the same methods). However, quantifying the variability in the data is neither obvious nor easy to do (how different is one data set from another?).

Suppose your professor splits the students in class into two groups: students on the left and students on the right. If \(\hat{p}_{_L}\) and \(\hat{p}_{_R}\) represent the proportion of students who own an Apple product on the left and right, respectively, would you be surprised if \(\hat{p}_{_L}\) did not exactly equal \(\hat{p}_{_R}\)?

While the proportions would probably be close to each other, it would be unusual for them to be exactly the same. We would probably observe a small difference due to chance.

If we don’t think the side of the room a person sits on in class is related to whether the person owns an Apple product, what assumption are we making about the relationship between these two variables? (Reminder: for these Guided Practice questions, you can check your answer in the footnote.)73

Studying randomness of this form is a key focus of statistics. Throughout this chapter, and those that follow, we provide two different approaches for quantifying the variability inherent in data: simulation-based methods and theory-based methods (mathematical models). Using the methods provided in this and future chapters, we will be able to draw conclusions beyond the data set at hand to research questions about larger populations.

5.1 Foundations of inference

Given results seen in a sample, the process of determining what we can infer to the population based on sample results is called statistical inference. Statistical inferential methods enable us to understand and quantify the uncertainty of our sample results. Statistical inference helps us answer two questions about the population:

- How strong is the evidence of an effect?

- How large is the effect?

The first question is answered through a hypothesis test, while the second is addressed with a confidence interval.

Statistical inference is the practice of making decisions and conclusions from data in the context of uncertainty. Errors do occur, just like rare events, and the data set at hand might lead us to the wrong conclusion. While a given data set may not always lead us to a correct conclusion, statistical inference gives us tools to control and evaluate how often these errors occur.

5.1.1 Motivating example: Martian alphabet

How well can humans distinguish one “Martian” letter from another? The Figure 5.1 displays two Martian letters—one is Kiki and the another is Bumba. Which do you think is Kiki and which do you think is Bumba?74

![Two Martian letters: Bumba and Kiki. Do you think the letter Bumba is on the left or the right?^[Bumba is the Martian letter on the left!]](05/images/bumBa-KiKi.png)

Figure 5.1: Two Martian letters: Bumba and Kiki. Do you think the letter Bumba is on the left or the right?75

This same image and question were presented to an introductory statistics class of 38 students. In that class, 34 students correctly identified Bumba as the Martian letter on the left. Assuming we can’t read Martian, is this result surprising?

One of two possibilities occurred:

- We can’t read Martian, and these results just occurred by chance.

- We can read Martian, and these results reflect this ability.

To decide between these two possibilities, we could calculate the probability of observing such results in a randomly selected sample of 38 students, under the assumption that students were just guessing. If this probability is very low, we’d have reason to reject the first possibility in favor of the second. We can calculate this probability using one of two methods:

- Simulation-based method: simulate lots of samples (Classes) of 38 students under the assumption that students are just guessing, then calculate the proportion of these simulated samples where we saw 34 or more students guessing correctly, or

- Theory-based method: develop a mathematical model for the sample proportion in this scenario and use the model to calculate the probability.

How could you use a coin or cards to simulate the guesses of one sample of 38 students who cannot read Martian?76

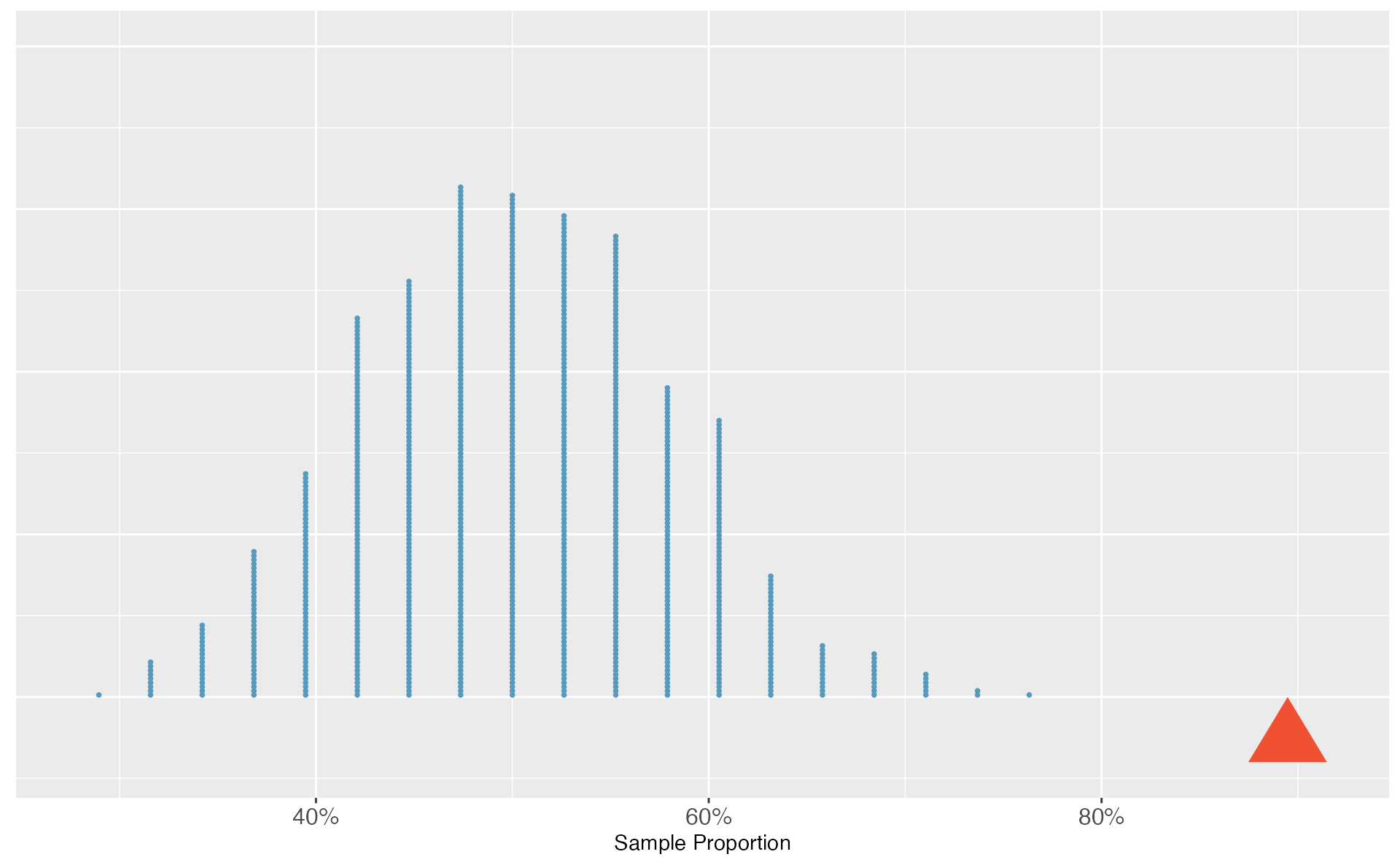

For this situation—since “just guessing” means you have a 50% chance of guessing correctly—we could simulate a sample of 38 students’ guesses by flipping a coin 38 times and counting the number of times it lands on heads. Using a computer to repeat this process 1,000 times, we create the dot plot in Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2: A dot plot of 1,000 sample proportions; each calculated by flipping a coin 38 times and calculating the proportion of times the coin landed on heads. None of the 1,000 simulations had sample proportion of at least 89%, which was the proportion observed in the study.

None of our simulated samples produce 34 of 38 correct guesses! That is, if students were just guessing, it is nearly impossible to observe 34 or more correct guesses in a sample of 38 students. Given this low probability, the more plausible possibility is 2. We can read Martian, and these results reflect this ability. We’ve just completed our first hypothesis test!

Now, obviously no one can read Martian, so a more realistic possibility is that humans tend to choose Bumba on the left more often than the right—there is a greater than 50% chance of choosing Bumba as the letter on the left. Even though we may think we’re guessing just by chance, we have a preference for Bumba on the left. It turns out that the explanation for this preference is called synesthesia, a tendency for humans to correlate sharp sounding noises (e.g., Kiki) with sharp looking images.77

But wait—we’re not done! We have evidence that humans tend to prefer Bumba on the left, but by how much? To answer this, we need a confidence interval—an interval of plausible values for the true probability humans will select Bumba as the left letter. The width of this interval is determined by how variable sample proportions are from sample to sample. It turns out, there is a mathematical model for this variability that we will explore later in this chapter. For now, let’s take the standard deviation from our simulated sample proportions as an estimate for this variability: 0.08. Since the simulated distribution of proportions is bell-shaped, we know about 95% of sample proportions should fall within two standard deviations of the true proportion, so we can add and subtract this margin of error to our sample proportion to calculate an approximate 95% confidence interval78: \[ \frac{34}{38} \pm 2\times 0.08 = 0.89 \pm 0.16 = (0.73, 1) \] Thus, based on this data, we are 95% confident that the probability a human guesses Bumba on the left is somewhere between 73% and 100%.

5.1.2 Variability in a statistic

There are two approaches to modeling how a statistic, such as a sample proportion, may vary from sample to sample. In the Martian alphabet example, we used a simulation-based approach to model this variability, using the standard deviation of the simulated distribution of sample proportions as a quantitative measure of this sampling variability. Simulation-based methods include the randomization tests and bootstrapping methods we will use in this textbook. We can also use a theory-based approach—one which makes use of mathematical modeling—and involves the normal and \(t\) probability distributions.

All of the theory-based methods discussed in this book work (under certain conditions) because of a very important theorem in Statistics called the Central Limit Theorem.

Central Limit Theorem.

For large sample sizes, the sampling distribution of a sample proportion (or sample mean) will appear to follow a bell-shaped curve called the normal distribution.

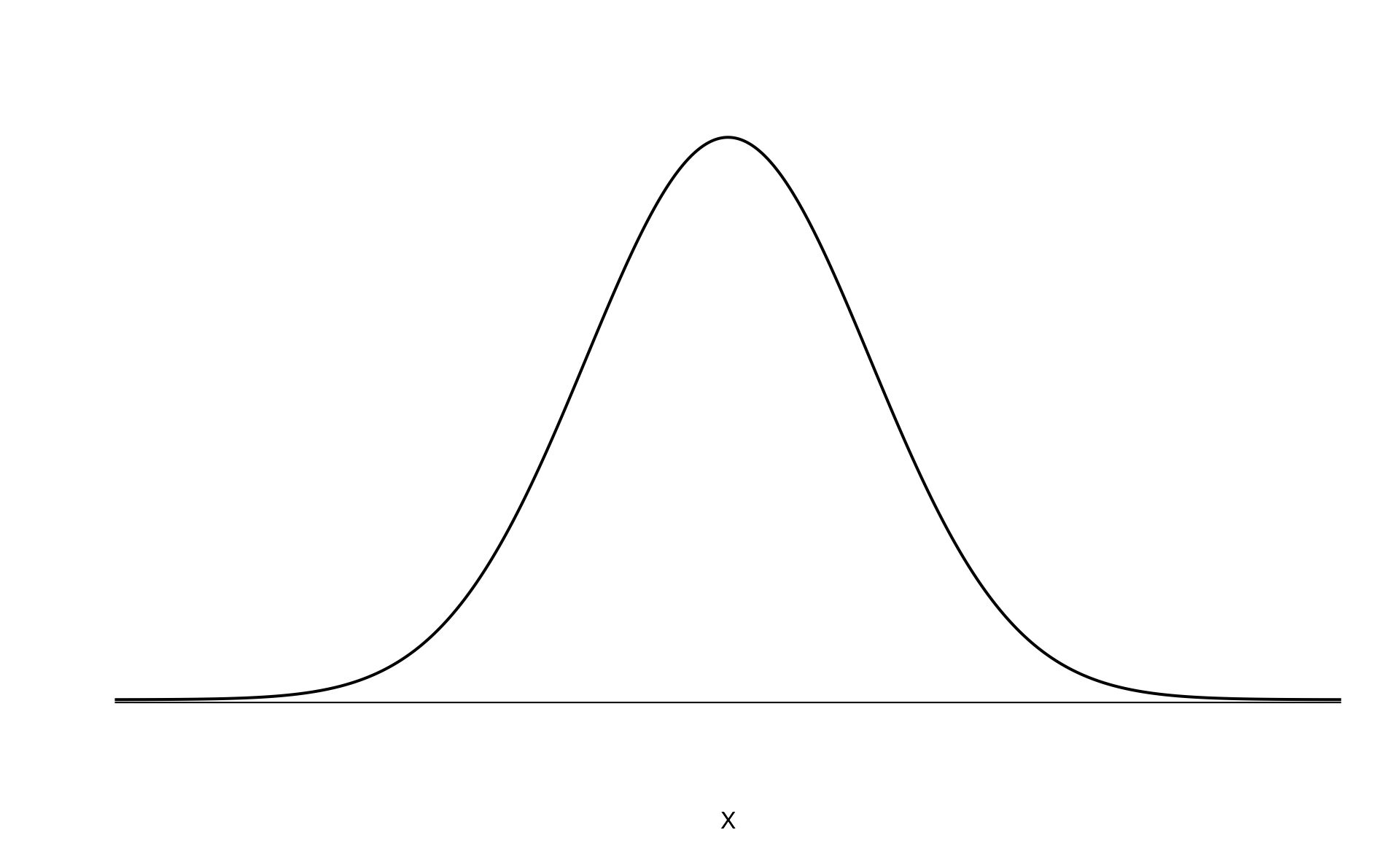

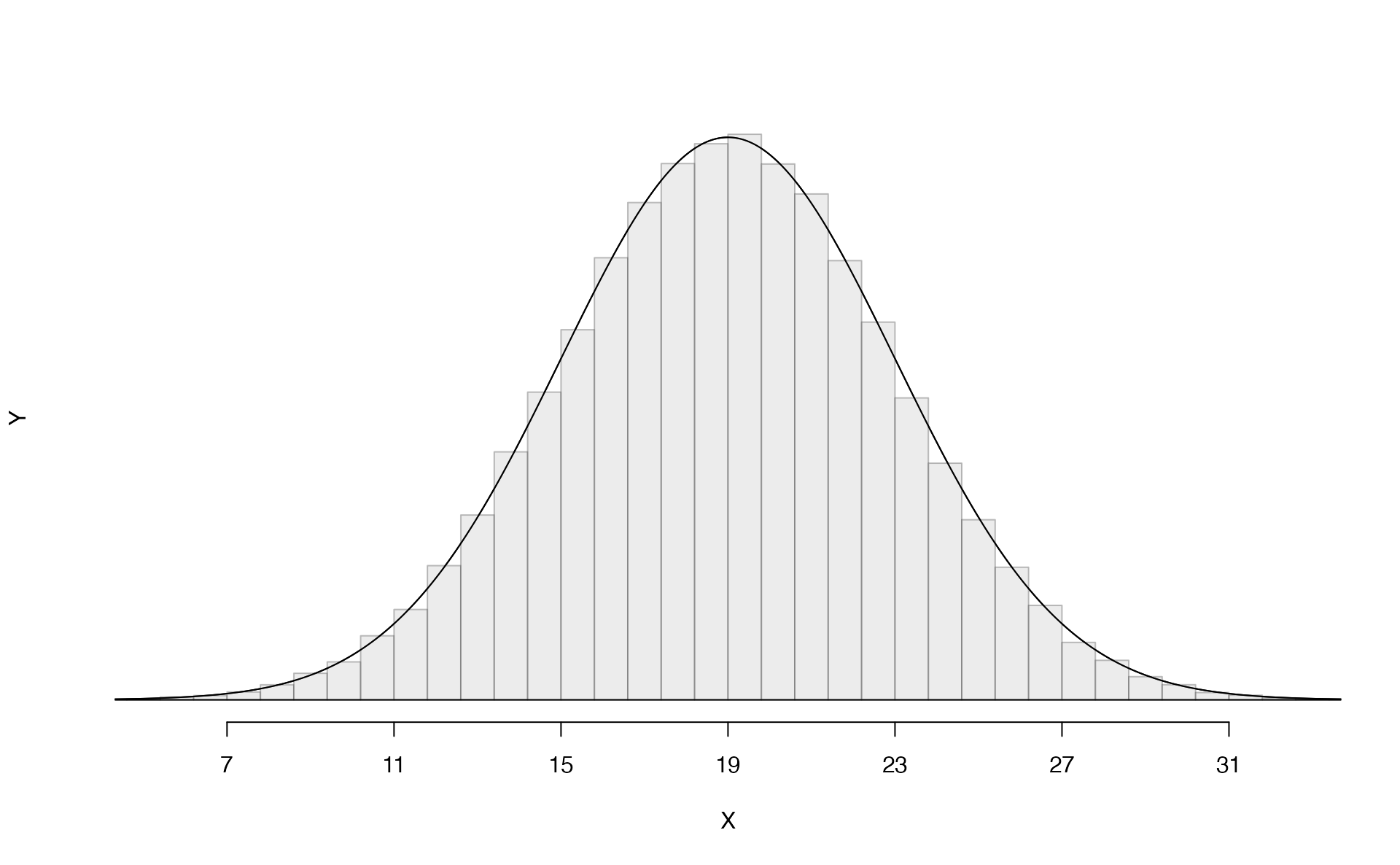

An example of a perfect normal distribution is shown in Figure 5.3. While the mean (center) and standard deviation (variability) may change for different scenarios, the general shape remains roughly intact.

Figure 5.3: A normal curve.

Recall from Chapter 2 that a distribution of a variable is a description of the possible values it takes and how frequently each value occurs. In a sampling distribution, our “variable” is a sample statistic, and the sampling distribution is a description of the possible values a sample statistic takes and how frequently each value occurs when looking across many many possible samples. It is quite amazing that something like a sample proportion, summarizing a categorical variable, will have a bell-shaped sampling distribution if we sample large enough samples!

Theory-based methods also give us mathematical expressions for the standard deviation of a sampling distribution. For instance, if the true population proportion is \(\pi\), then the standard deviation of the sampling distribution of sample proportions—how far away we would expect a sample proportion to be away from the population proportion—is79 \[ SD(\hat{p}) = \sqrt{\frac{\pi(1-\pi)}{n}}. \] Typically, values of parameters such as \(\pi\) are unknown, so we are unable to calculate these standard deviations. In this case, we substitute our “best guess” for \(\pi\) in the formulas, either from a hypothesis or from a point estimate.

Standard error.

The standard deviation of a sampling distribution for a statistic, denoted by \(SD\)(statistic), represents how far away we would expect the statistic to land from the parameter.

Since the formulas for these standard deviations depend on unknown parameters, we substitute our “best guess” for \(\pi\) in the formulas, either from a hypothesis or from a point estimate. The resulting estimated standard deviation is called the standard error of the statistic, denoted by \(SE\)(statistic).

5.1.3 Hypothesis tests

In the Martian alphabet example, we utilized a hypothesis test, which is a formal technique for evaluating two competing possibilities. Each hypothesis test involves a null hypothesis, which represents either a skeptical perspective or a perspective of no difference or no effect, and an alternative hypothesis, which represents a new perspective such as the possibility that there has been a change or that there is a treatment effect in an experiment. The alternative hypothesis is usually the reason the scientists set out to do the research in the first place.

Null and alternative hypotheses.

When we observe an effect in a sample, we would like to determine if this observed effect represents an actual effect in the population, or whether it was simply due to chance. We label these two competing claims, \(H_0\) and \(H_A\), which are spoken as “H-naught” and “H_A”.

The null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) often represents either a skeptical perspective or a claim to be tested. The alternative hypothesis (\(H_A\)) represents an alternative claim under consideration and is often represented by a range of possible values for the parameter of interest.

In the Martian alphabet example, which of the two competing possibilities was the null hypothesis? the alternative hypothesis?80

The hypothesis testing framework is a very general tool, and we often use it without a second thought. If a person makes a somewhat unbelievable claim, we are initially skeptical. However, if there is sufficient evidence that supports the claim, we set aside our skepticism. The hallmarks of hypothesis testing are also found in the US court system.

The US court system

A US court considers two possible claims about a defendant: they are either innocent or guilty. If we set these claims up in a hypothesis framework, which would be the null hypothesis and which the alternative?

The jury considers whether the evidence is so convincing (strong) that there is no reasonable doubt regarding the person’s guilt. That is, the skeptical perspective (null hypothesis) is that the person is innocent until evidence is presented that convinces the jury that the person is guilty (alternative hypothesis). Analogously, in a hypothesis test, we assume the null hypothesis until evidence is presented that convinces us the alternative hypothesis is true.

Jurors examine the evidence to see whether it convincingly shows a defendant is guilty. Notice that if a jury finds a defendant not guilty, this does not necessarily mean the jury is confident in the person’s innocence. They are simply not convinced of the alternative that the person is guilty.

This is also the case with hypothesis testing: even if we fail to reject the null hypothesis, we typically do not accept the null hypothesis as truth. Failing to find strong evidence for the alternative hypothesis is not equivalent to providing evidence that the null hypothesis is true.

p-value

In the Martian alphabet example, we performed a simulation-based hypothesis test of the hypotheses:

\(H_0\): The chance a human chooses Bumba on the left is 50%.

\(H_A\): Humans have a preference for choosing Bumba on the left.

The research question—can humans read Martian?—was framed in the context of these hypotheses.

The null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) was a perspective of no effect (no ability to read Martian). The student data provided a point estimate of 89.5% (\(34/38 \times 100\)%) for the true probability of choosing Bumba on the left. We determined that observing such a sample proportion from chance alone (assuming \(H_0\)) would be rare—it would only happen in less than 1 out of 1000 samples. When results like these are inconsistent with \(H_0\), we reject \(H_0\) in favor of \(H_A\). Here, we concluded that humans have a preference for choosing Bumba on the left.

The less than 1-in-1000 chance is what we call a p-value, which is a probability quantifying the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis and in favor of the alternative.

p-value.

The p-value is the probability of observing data at least as favorable to the alternative hypothesis as our current data set, if the null hypothesis were true. We typically use a summary statistic of the data, such as a proportion or difference in proportions, to help compute the p-value and evaluate the hypotheses. This summary value that is used to compute the p-value is often called the test statistic.

When interpreting a p-value, remember that the definition of a p-value has three components. It is a (1) probability. What it is the probability of? It is the probability of (2) our observed sample statistic or one more extreme. Assuming what? It is the probability of our observed sample statistic or one more extreme, (3) assuming the null hypothesis is true:

- probability

- data81

- null hypothesis

What was the test statistic in the Martian alphabet example?

The test statistic in the the Martian alphabet example was the sample proportion, \(\frac{34}{38} = 0.895\) (or 89.5%). This is also the point estimate of the true probability that humans would choose Bumba on the left.

Since the p-value is a probability, its value will always be between 0 and 1. The closer the p-value is to 0, the stronger the evidence we have against the null hypothesis. Why? A small p-value means that our data are unlikely to occur, if the null hypothesis is true. We take that to mean that the null hypothesis isn’t a plausible assumption, and we reject it. This process mimics the scientific method—it is easier to disprove a theory than prove it. If scientists want to find evidence that a new drug reduces the risk of stroke, then they assume it doesn’t reduce the risk of stroke and then show that the observed data are so unlikely to occur that the more plausible explanation is that the drug works.

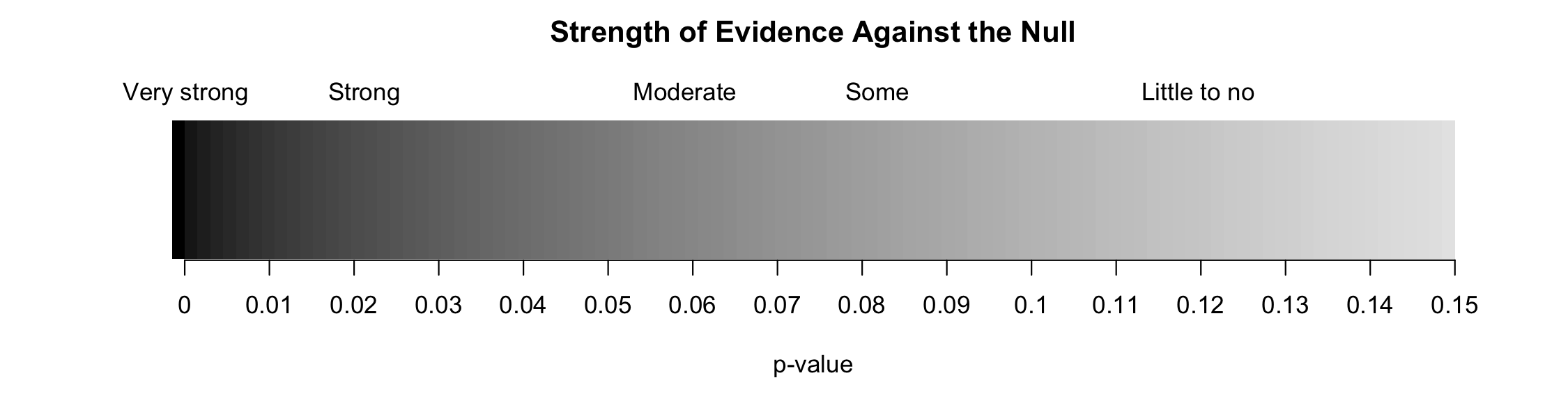

Think of p-values as a continuum of strength of evidence against the null, from 0 (extremely strong evidence) to 1 (no evidence). Beyond around 10%, the data provide no evidence against the null hypothesis. Be careful not to equate this with evidence for the null hypothesis, which is incorrect.

The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Figure 5.4: Strength of evidence against the null for a continuum of p-values. Once the p-value is beyond around 0.10, the data provide no evidence against the null hypothesis.

Regardless of the data structure or analysis method, the hypothesis testing framework always follows the same steps—only the details for how we model randomness in the data change.

General steps of a hypothesis test. Every hypothesis test follows these same general steps:

- Frame the research question in terms of hypotheses.

- Collect and summarize data using a test statistic.

- Assume the null hypothesis is true, and simulate or mathematically model a null distribution for the test statistic.

- Compare the observed test statistic to the null distribution to calculate a p-value.

- Make a conclusion based on the p-value, and write a conclusion in context, in plain language, and in terms of the alternative hypothesis.

Decisions and statistical significance

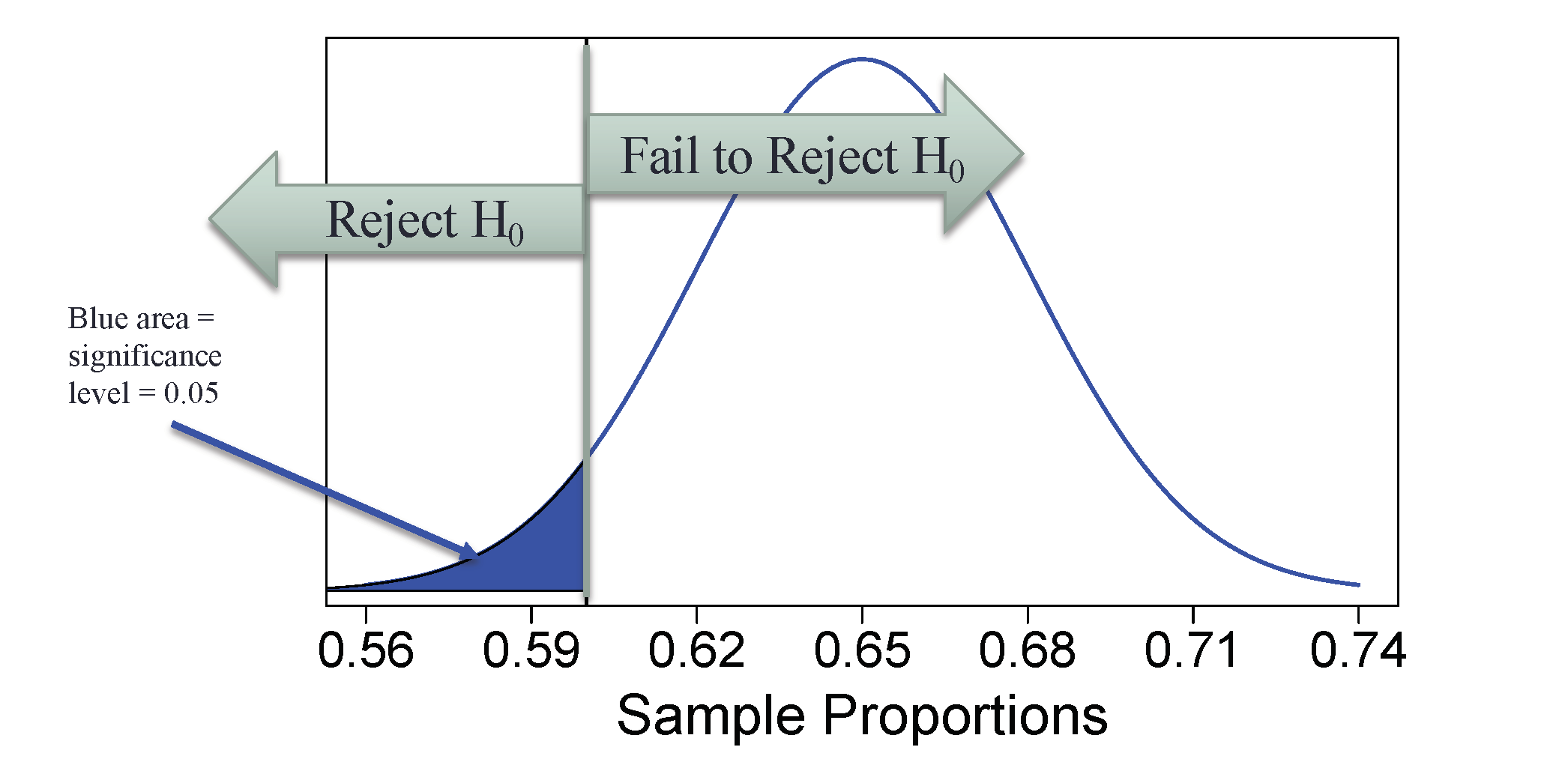

In some cases, a decision to the hypothesis test is needed, with the two possible decisions as follows:

- Reject the null hypothesis

- Fail to reject the null hypothesis

For which values of the p-value should you “reject” a null hypothesis? “fail to reject” a null hypothesis?82

In order to decide between these two options, we need a previously set threshold for our p-value: when the p-value is less than a previously set threshold, we reject \(H_0\); otherwise, we fail to reject \(H_0\). This threshold is called the significance level, and when the p-value is less than the significance level, we say the results are statistically significant. This means the data provide such strong evidence against \(H_0\) that we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. The significance level, often represented by \(\alpha\) (the Greek letter alpha), is typically set to \(\alpha = 0.05\), but can vary depending on the field or the application and the real-life consequences of an incorrect decision. Using a significance level of \(\alpha = 0.05\) in the Martian alphabet study, we can say that the data provided statistically significant evidence against the null hypothesis.

Statistical significance.

We say that the data provide statistically significant evidence against the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than some reference value called the significance level, denoted by \(\alpha\).

What’s so special about 0.05?

We often use a threshold of 0.05 to determine whether a result is statistically significant. But why 0.05? Maybe we should use a bigger number, or maybe a smaller number. If you’re a little puzzled, that probably means you’re reading with a critical eye—good job! The OpenIntro authors have a video to help clarify why 0.05:

Sometimes it’s also a good idea to deviate from the standard. We’ll discuss when to choose a threshold different than 0.05 in Section 5.5.1.

Statistical significance has been a hot topic in the news, related to the “reproducibility crisis” in some scientific fields. We encourage you to read more about the debate on the use of p-values and statistical significance. A good place to start would be the Nature article, “Scientists rise up against statistical significance,” from March 20, 2019.

5.1.4 Confidence intervals

A point estimate provides a single plausible value for a parameter. However, a point estimate is rarely perfect—usually there is some error in the estimate. In addition to supplying a point estimate of a parameter, a next logical step would be to provide a plausible range of values for the parameter.

A plausible range of values for the population parameter is called a confidence interval. Using only a single point estimate is like fishing in a murky lake with a spear, and using a confidence interval is like fishing with a net. We can throw a spear where we saw a fish, but we will probably miss. On the other hand, if we toss a net in that area, we have a good chance of catching the fish.

If we report a point estimate, we probably will not hit the exact population parameter. On the other hand, if we report a range of plausible values—a confidence interval—we have a good shot at capturing the parameter.

This reasoning also explains why we can never prove a null hypothesis. Sample statistics will vary from sample to sample. While we can quantify this uncertainty (e.g., we are 95% sure the statistic is within 0.15 of the parameter), we can never be certain that the parameter is an exact value. For example, suppose you want to test whether a coin is a fair coin, i.e., \(H_0: \pi = 0.50\) versus \(H_0: \pi \neq 0.50\), so you toss the coin 10 times to collect data. In those 10 tosses, 6 land on heads and 4 land on tails, resulting in a p-value of 0.75483. We don’t have enough evidence to show that the coin is biased, but surely we wouldn’t say we just proved the coin is fair!

There are only two possible decisions in a hypothesis test: (1) reject \(H_0\), or (2) fail to reject \(H_0\). Since one can never prove a null hypothesis—we can only disprove84 it—we never have the ability to “accept the null.” You may have seen this phrase in other textbooks or articles, but it is incorrect.

If we want to be very certain we capture the population parameter, should we use a wider interval or a smaller interval?85

We will explore both simulation-based methods (bootstrapping) and theory-based methods for creating confidence intervals in this text. Though the details change with different scenarios, theory-based confidence intervals will always take the form: \[ \mbox{statistic} \pm (\mbox{multiplier}) \times (\mbox{standard error of the statistic}) \] The statistic is our best guess for the value of the parameter, so it makes sense to build the confidence interval around that value. The standard error, which is a measure of the uncertainty associated with the statistic, provides a guide for how large we should make the confidence interval. The multiplier is determined by how confident we’d like to be, and tells us how many standard errors we need to add and subtract from the statistic. The amount we add and subtract from the statistic is called the margin of error.

General form of a confidence interval.

The general form of a theory-based confidence interval for an unknown parameter is \[ \mbox{statistic} \pm (\mbox{multiplier}) \times (\mbox{standard error of the statistic}) \] The amount we add and subtract to the statistic to calculate the confidence interval is called the margin of error. \[ \mbox{margin of error} = (\mbox{multiplier}) \times (\mbox{standard error of the statistic}) \]

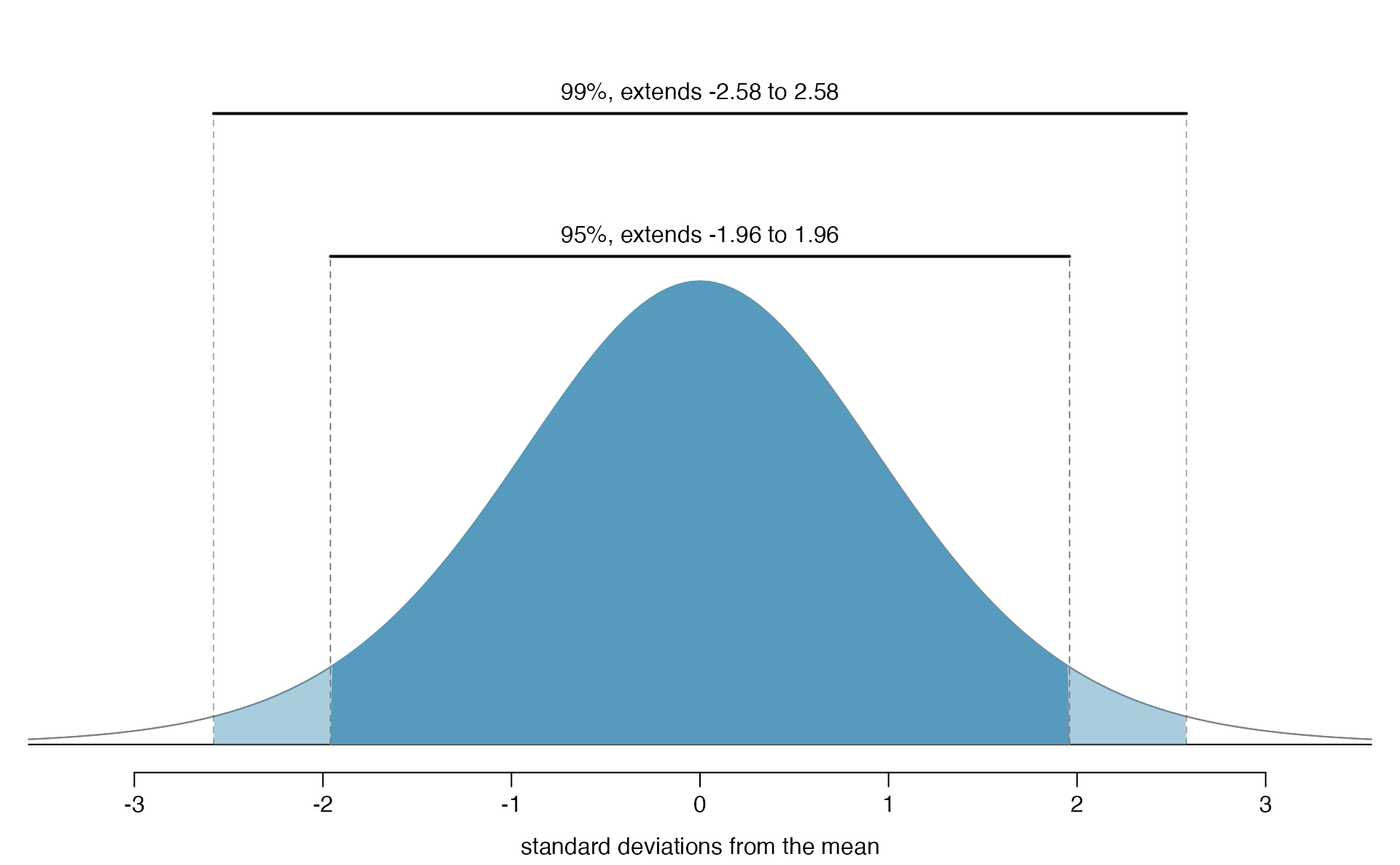

In Section 5.3.4 we will discuss different percentages for the confidence interval (e.g., 90% confidence interval or 99% confidence interval). Section 5.5.2 provides a longer discussion on what “95% confidence” actually means.

5.2 The normal distribution

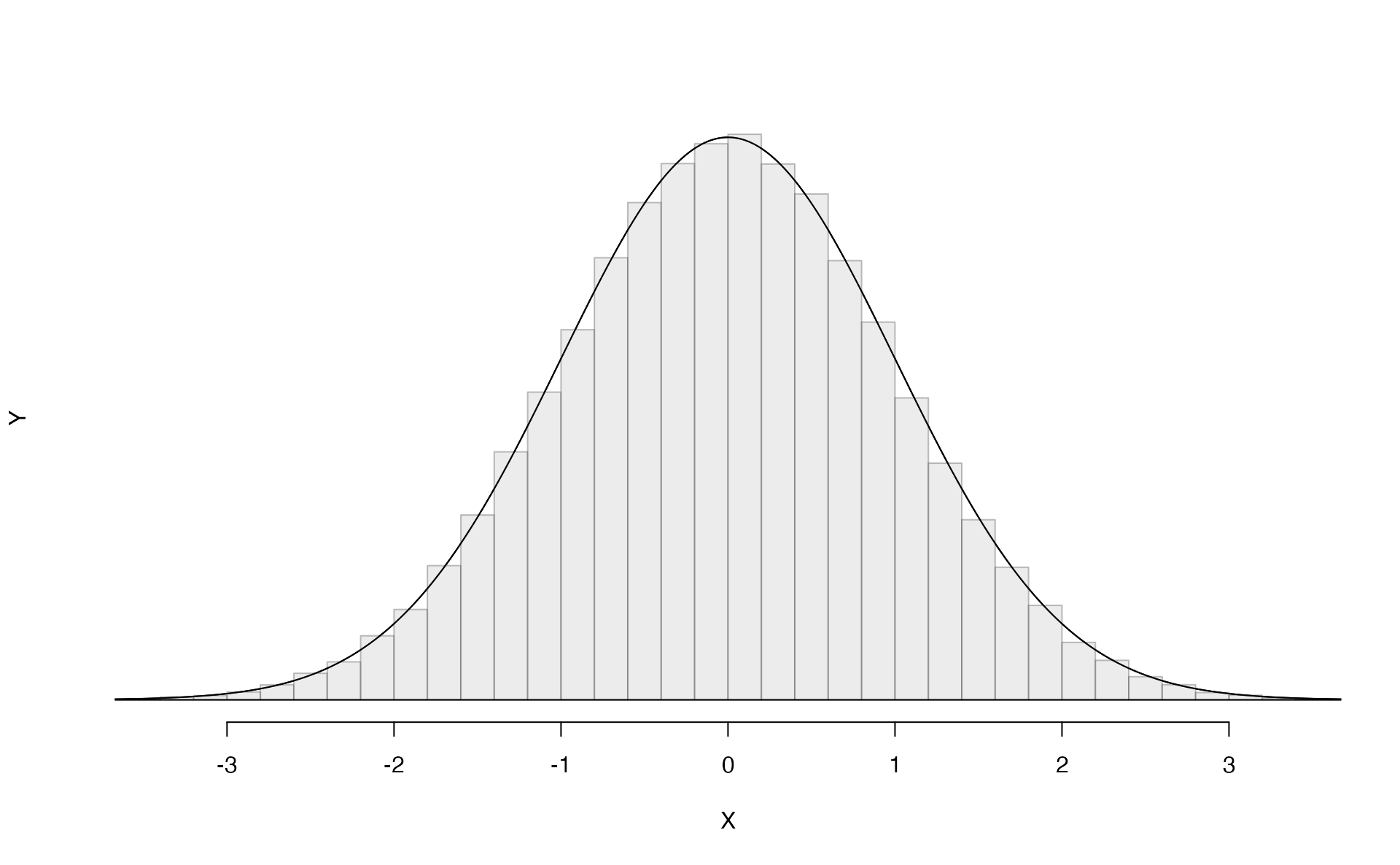

Among all the distributions we see in statistics, one is overwhelmingly the most common. The symmetric, unimodal, bell curve is ubiquitous throughout statistics. It is so common that people know it as a variety of names including the normal curve, normal model, or normal distribution.86 Under certain conditions, sample proportions, sample means, and sample differences can be modeled using the normal distribution—the basis for our theory-based inference methods. Additionally, some variables such as SAT scores and heights of US adult males closely follow the normal distribution.

Normal distribution facts.

Many summary statistics and variables are nearly normal, but none are exactly normal. Thus the normal distribution, while not perfect for any single problem, is very useful for a variety of problems. We will use it in data exploration and to solve important problems in statistics.

In this section, we will discuss the normal distribution in the context of data to become more familiar with normal distribution techniques.

5.2.1 Normal distribution model

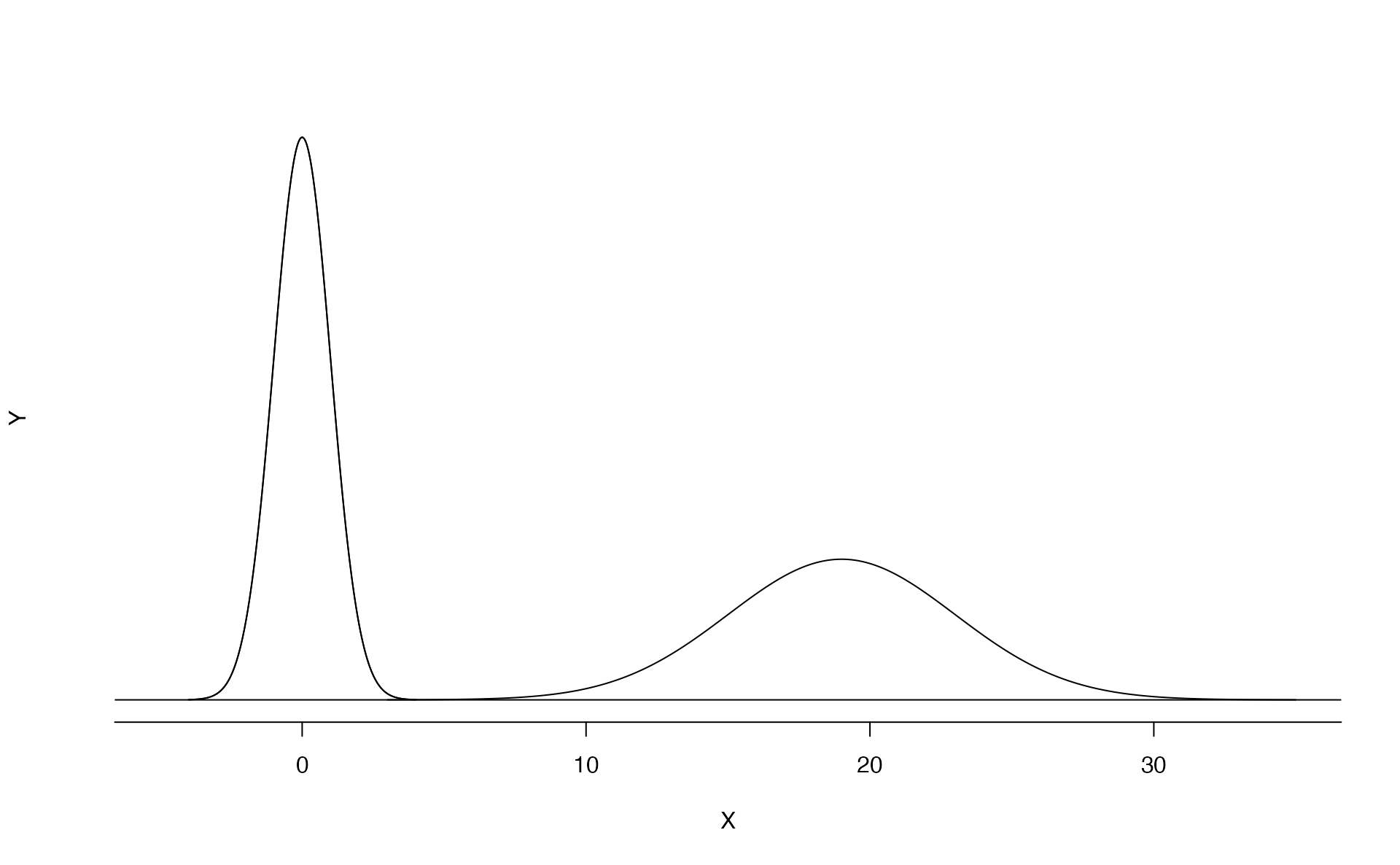

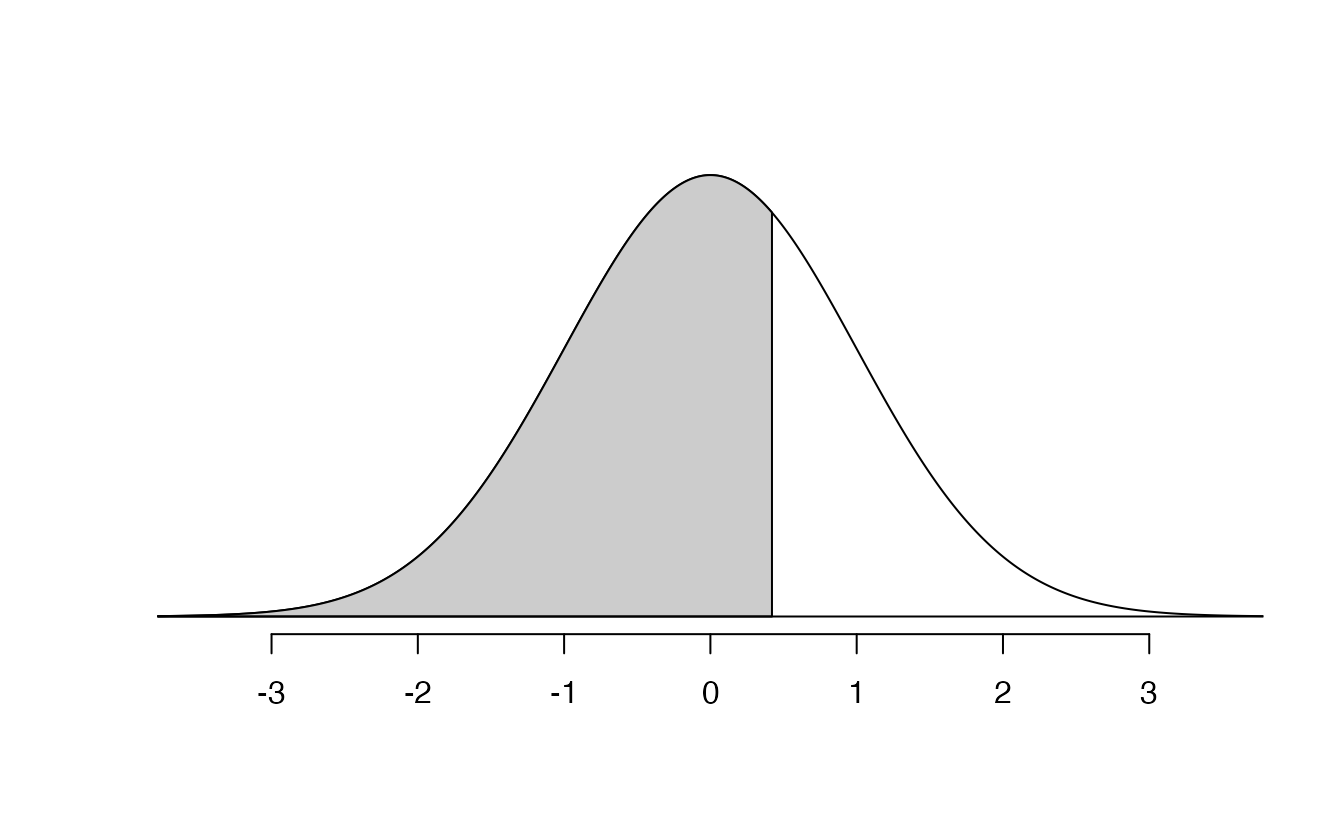

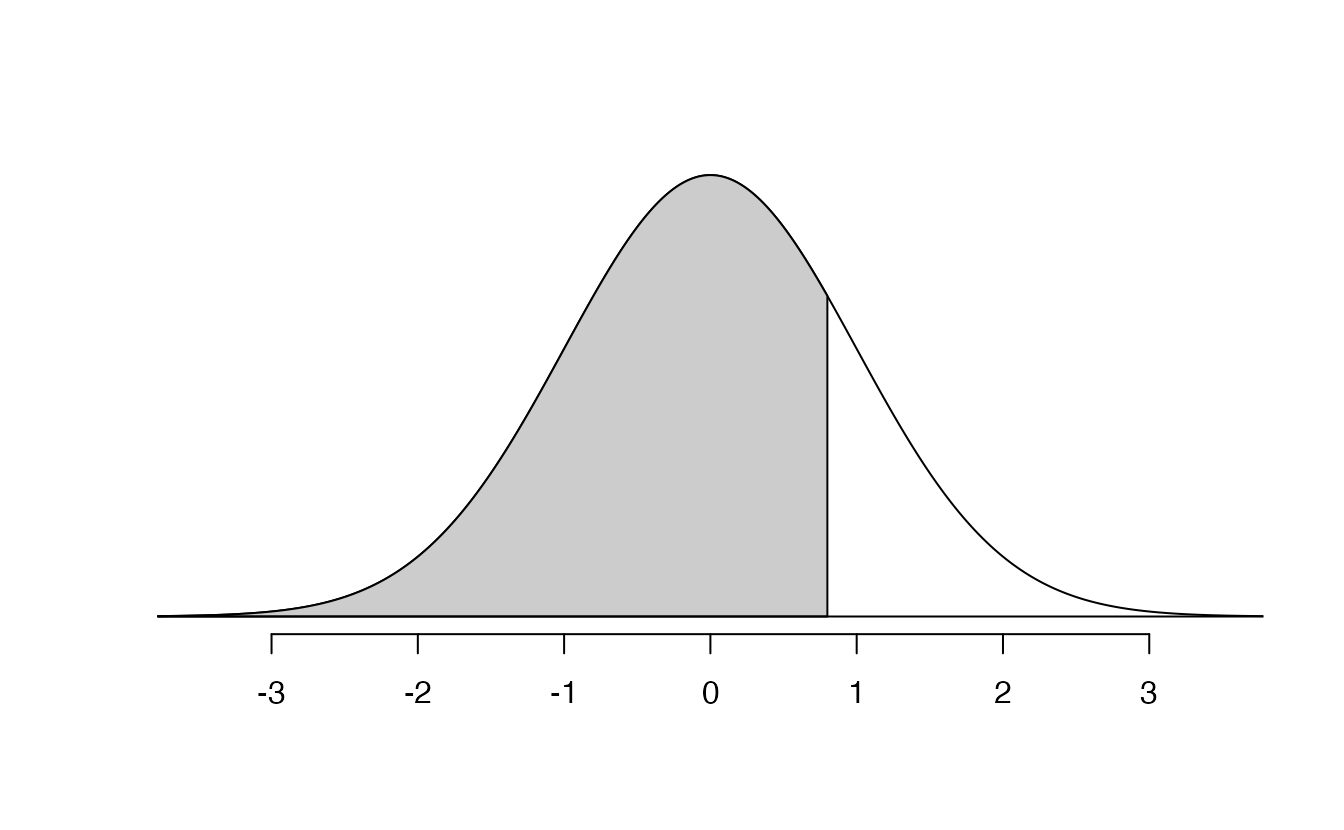

The normal distribution always describes a symmetric, unimodal, bell-shaped curve. However, normal curves can look different depending on the details of the model. Specifically, the normal model can be adjusted using two parameters: mean and standard deviation. As you can probably guess, changing the mean shifts the bell curve to the left or right, while changing the standard deviation stretches or constricts the curve. Figure 5.5 shows the normal distribution with mean \(0\) and standard deviation \(1\) (which is commonly referred to as the standard normal distribution) on top. A normal distribution with mean \(19\) and standard deviation \(4\) is shown on the bottom. Figure 5.6 shows the same two normal distributions on the same axis.

Figure 5.5: Both curves represent the normal distribution, however, they differ in their center and spread. The normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 1 is called the standard normal distribution.

Figure 5.6: The two normal models shown above and now plotted together on the same scale.

If a normal distribution has mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\), we may write the distribution as \(N(\mu, \sigma)\). The two distributions in Figure 5.6 can be written as \[\begin{align*} N(\mu=0,\sigma=1)\quad\text{and}\quad N(\mu=19,\sigma=4) \end{align*}\] Because the mean and standard deviation describe a normal distribution exactly, they are called the distribution’s parameters.

Write down the short-hand for a normal distribution with (a) mean 5 and standard deviation 3, (b) mean -100 and standard deviation 10, and (c) mean 2 and standard deviation 9.87

5.2.2 Standardizing with Z-scores

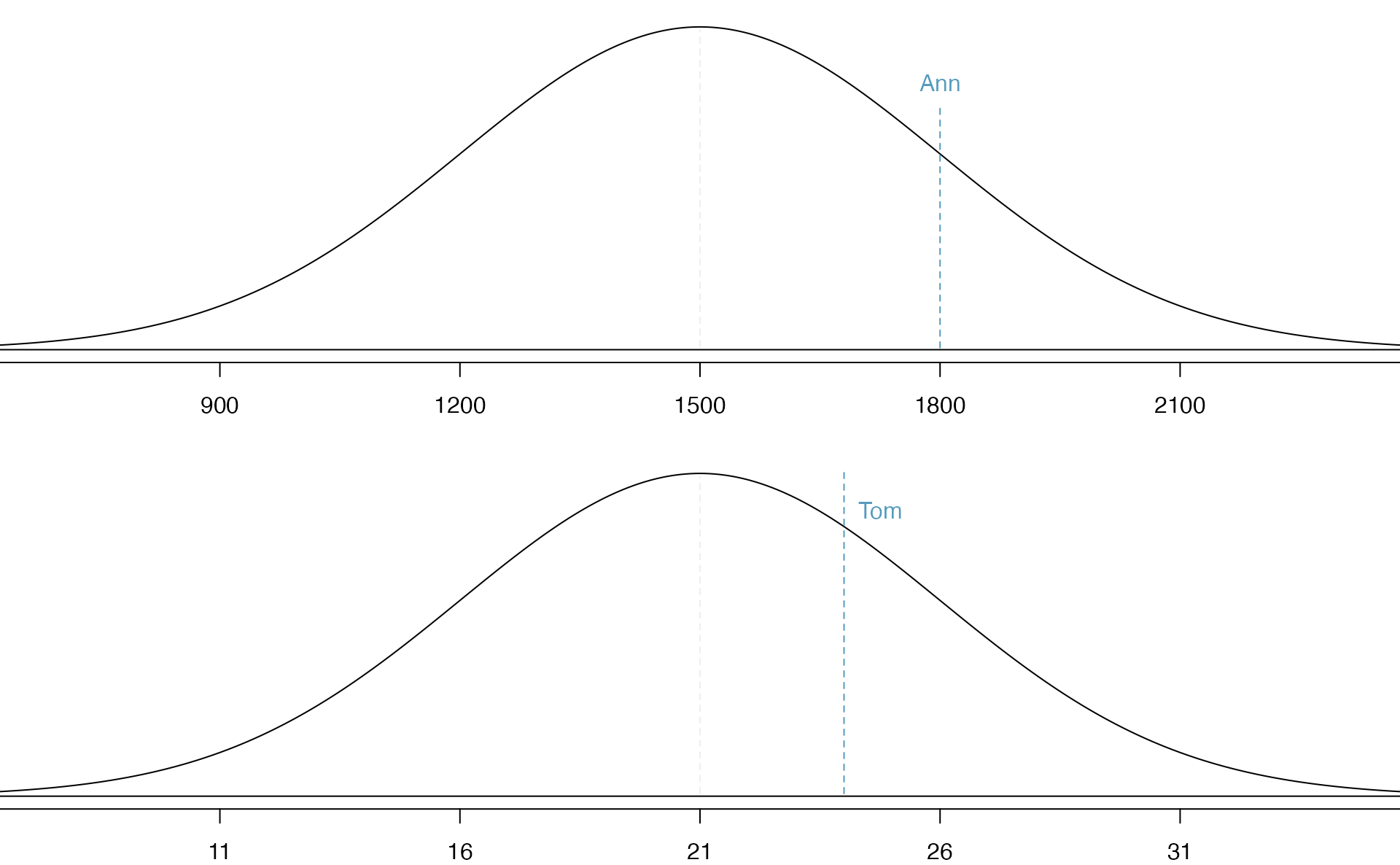

Table 5.1 shows the mean and standard deviation for total scores on the SAT and ACT. The distribution of SAT and ACT scores are both nearly normal. Suppose Ann scored 1800 on her SAT and Tom scored 24 on his ACT. Who performed better?88

| SAT | ACT | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1500 | 21 |

| SD | 300 | 5 |

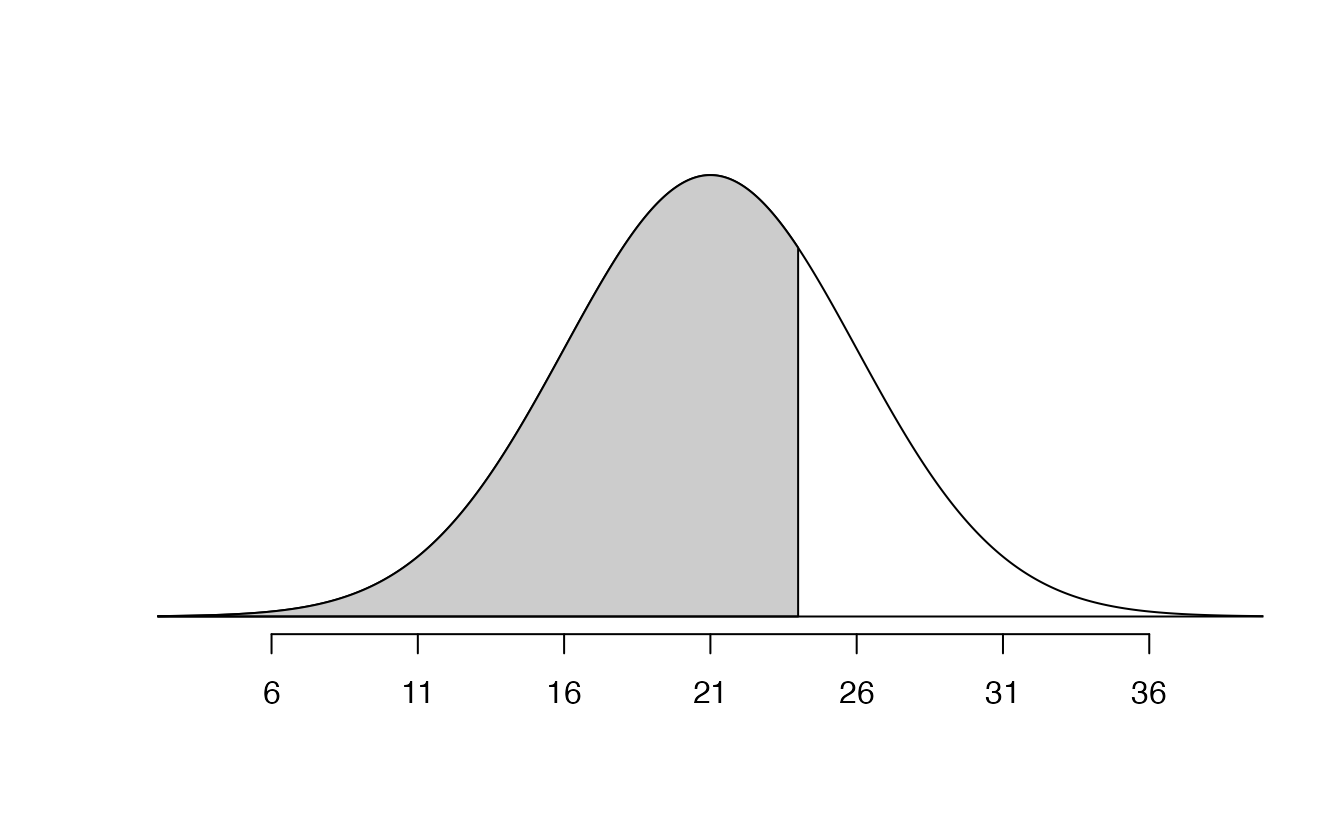

Figure 5.7: Ann’s and Tom’s scores shown with the distributions of SAT and ACT scores.

The solution to the previous example relies on a standardization technique called a Z-score, a method most commonly employed for nearly normal observations (but that may be used with any distribution). The Z-score of an observation is defined as the number of standard deviations it falls above or below the mean. If the observation is one standard deviation above the mean, its Z-score is 1. If it is 1.5 standard deviations below the mean, then its Z-score is -1.5. If \(x\) is an observation from a distribution \(N(\mu, \sigma)\), we define the Z-score mathematically as

\[\begin{eqnarray*} Z = \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} \end{eqnarray*}\] Using \(\mu_{SAT}=1500\), \(\sigma_{SAT}=300\), and \(x_{Ann}=1800\), we find Ann’s Z-score: \[\begin{eqnarray*} Z_{Ann} = \frac{x_{Ann} - \mu_{SAT}}{\sigma_{SAT}} = \frac{1800-1500}{300} = 1 \end{eqnarray*}\]

The Z-score.

The Z-score of an observation is the number of standard deviations it falls above or below the mean. We compute the Z-score for an observation \(x\) that follows a distribution with mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\) by first subtracting its mean, then dividing by its standard deviation: \[\begin{eqnarray*} Z = \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} \end{eqnarray*}\]

Use Tom’s ACT score, 24, along with the ACT mean and standard deviation to compute his Z-score.89

Observations above the mean always have positive Z-scores while those below the mean have negative Z-scores. If an observation is equal to the mean (e.g., SAT score of 1500), then the Z-score is \(0\).

Let \(X\) represent a random variable from \(N(\mu=3, \sigma=2)\), and suppose we observe \(x=5.19\). (a) Find the Z-score of \(x\). (b) Use the Z-score to determine how many standard deviations above or below the mean \(x\) falls.90

Head lengths of brushtail possums follow a nearly normal distribution with mean 92.6 mm and standard deviation 3.6 mm. Compute the Z-scores for possums with head lengths of 95.4 mm and 85.8 mm.91

We can use Z-scores to roughly identify which observations are more unusual than others. One observation \(x_1\) is said to be more unusual than another observation \(x_2\) if the absolute value of its Z-score is larger than the absolute value of the other observation’s Z-score: \(|Z_1| > |Z_2|\). This technique is especially insightful when a distribution is symmetric.

Which of the two brushtail possum observations in the previous guided practice is more unusual?92

5.2.3 Normal probability calculations in R

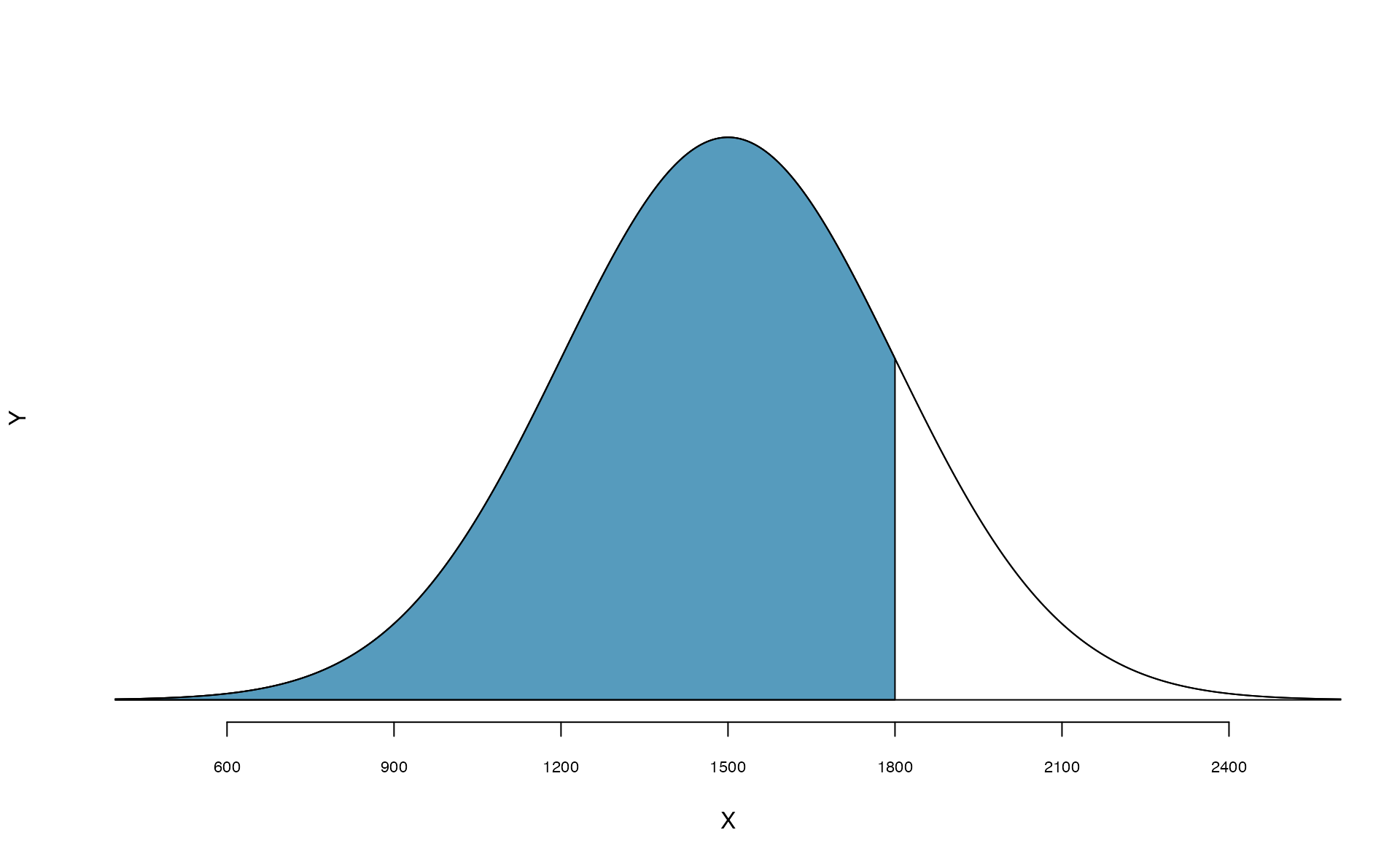

Ann from the SAT Guided Practice earned a score of 1800 on her SAT with a corresponding \(Z=1\). She would like to know what percentile she falls in among all SAT test-takers.

Ann’s percentile is the percentage of people who earned a lower SAT score than Ann. We shade the area representing those individuals in Figure 5.8. The total area under the normal curve is always equal to 1, and the proportion of people who scored below Ann on the SAT is equal to the area shaded in Figure 5.8: 0.8413. In other words, Ann is in the \(84^{th}\) percentile of SAT takers.

Figure 5.8: The normal model for SAT scores, shading the area of those individuals who scored below Ann.

We can use the normal model to find percentiles or probabilities. In R, the function to calculate normal probabilities is pnorm(). The normTail() function is available in the openintro R package and will draw the associated curve if it is helpful. In the code below, we find the percentile of \(Z=0.43\) is 0.6664, or the \(66.64^{th}\) percentile.

We can also find the Z-score associated with a percentile. For example, to identify Z for the \(80^{th}\) percentile, we use qnorm() which identifies the quantile for a given percentage. The quantile represents the cutoff value.93 We determine the Z-score for the \(80^{th}\) percentile using qnorm(): 0.84.

We can use these functions with other normal distributions than the standard normal distribution by specifying the mean as the argument for m and the standard deviation as the argument for s. Here we determine the proportion of ACT test takers who scored worse than Tom on the ACT: 0.73.

Determine the proportion of SAT test takers who scored better than Ann on the SAT.94

5.2.4 Normal probability examples

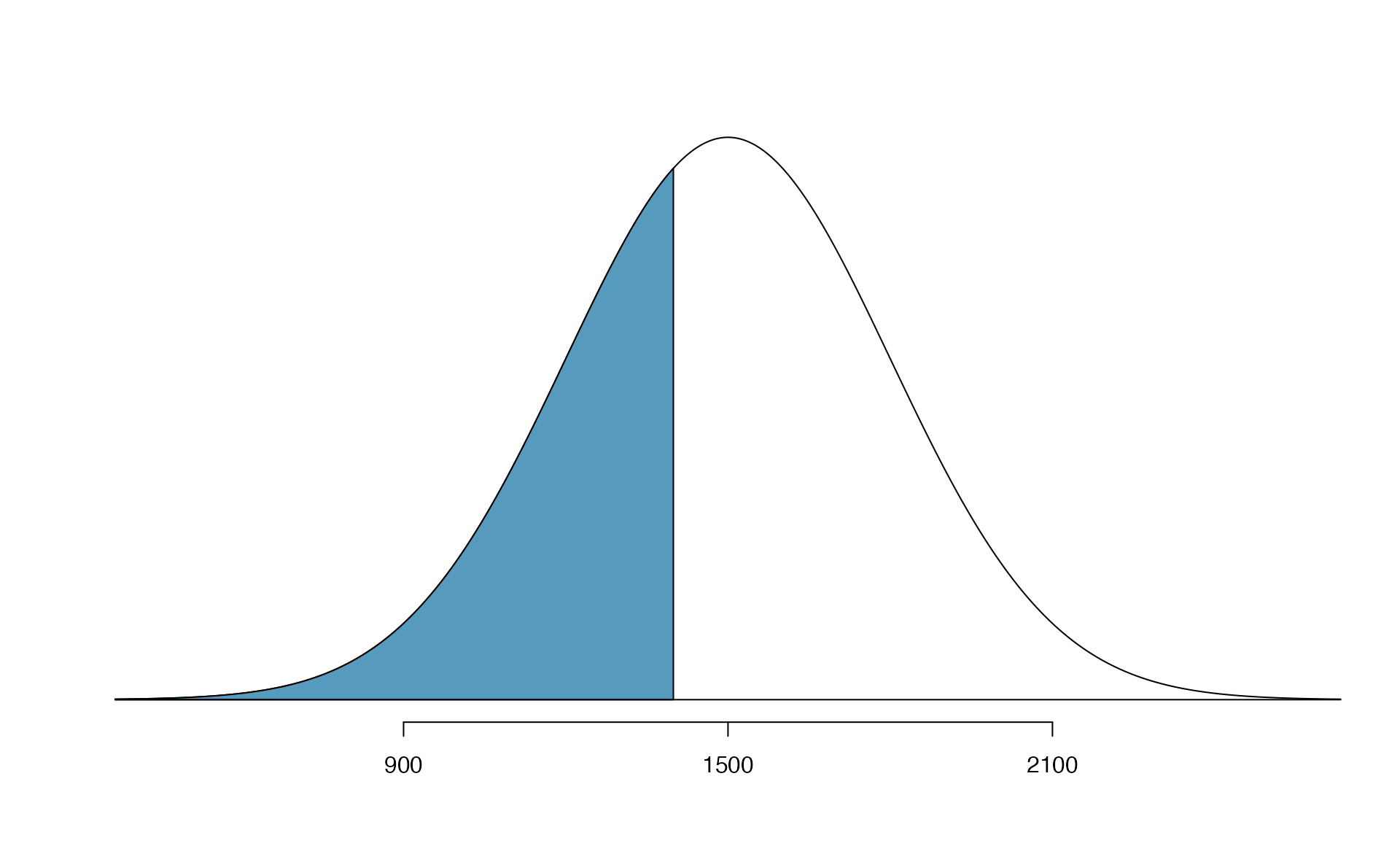

Cumulative SAT scores are approximated well by a normal model, \(N(\mu=1500, \sigma=300)\).

Shannon is a randomly selected SAT taker, and nothing is known about Shannon’s SAT aptitude. What is the probability that Shannon scores at least 1630 on her SATs?

First, always draw and label a picture of the normal distribution. (Drawings need not be exact to be useful.) We are interested in the chance she scores above 1630, so we shade the upper tail. See the normal curve below.

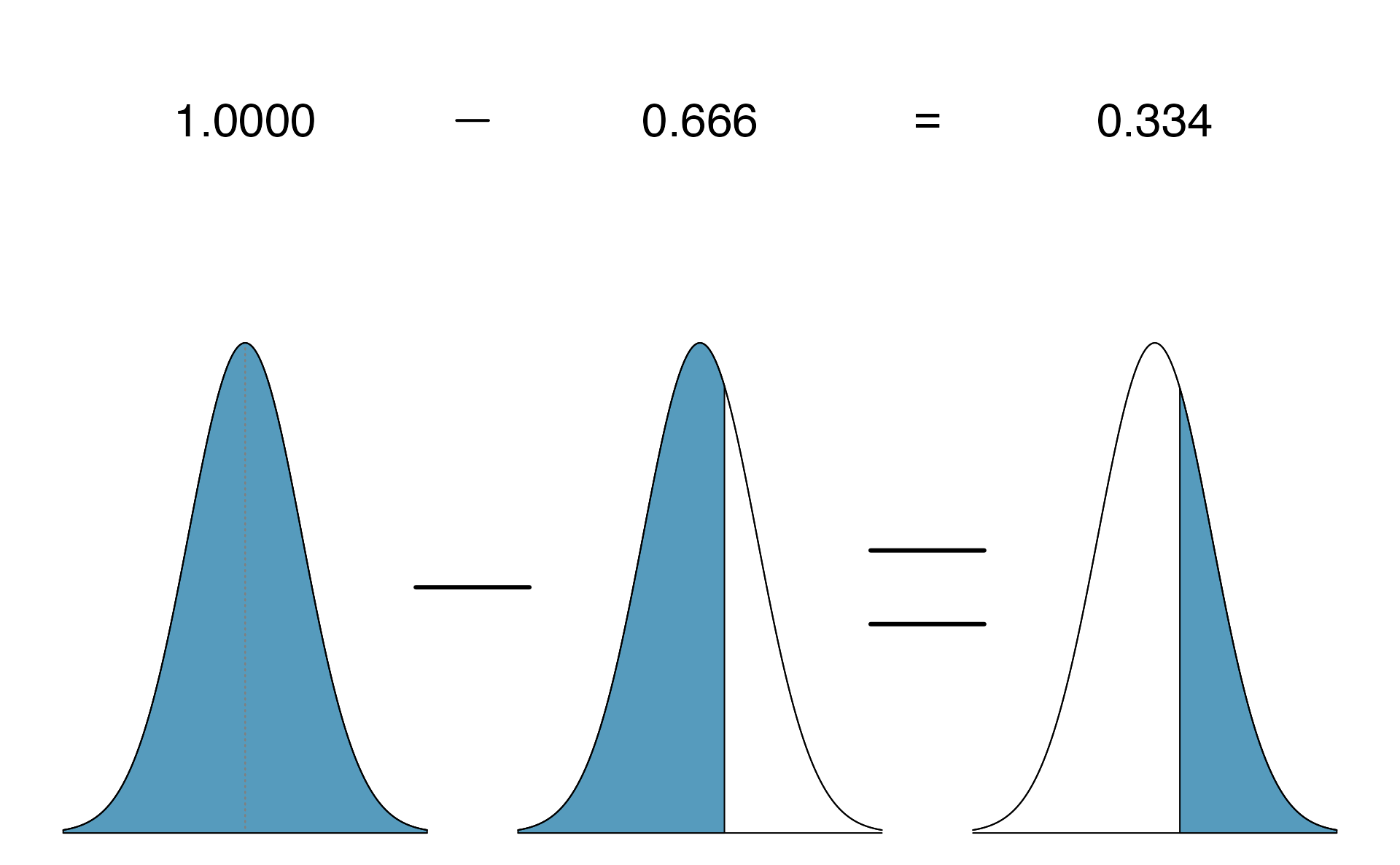

The picture shows the mean and the values at 2 standard deviations above and below the mean. The simplest way to find the shaded area under the curve makes use of the Z-score of the cutoff value. With \(\mu=1500\), \(\sigma=300\), and the cutoff value \(x=1630\), the Z-score is computed as \[\begin{eqnarray*} Z = \frac{x - \mu}{\sigma} = \frac{1630 - 1500}{300} = \frac{130}{300} = 0.43 \end{eqnarray*}\] We use software to find the percentile of \(Z=0.43\), which yields 0.6664. However, the percentile describes those who had a Z-score lower than 0.43. To find the area above \(Z=0.43\), we compute one minus the area of the lower tail, as seen below.

The probability Shannon scores at least 1630 on the SAT is 0.3336.

Always draw a picture first, and find the Z-score second.

For any normal probability situation, always always always draw and label the normal curve and shade the area of interest first. The picture will provide an estimate of the probability.

After drawing a figure to represent the situation, identify the Z-score for the observation of interest.

If the probability of Shannon scoring at least 1630 is 0.3336, then what is the probability she scores less than 1630? Draw the normal curve representing this exercise, shading the lower region instead of the upper one.95

Edward earned a 1400 on his SAT. What is his percentile?

First, a picture is needed. Edward’s percentile is the proportion of people who do not get as high as a 1400. These are the scores to the left of 1400.

Identifying the mean \(\mu=1500\), the standard deviation \(\sigma=300\), and the cutoff for the tail area \(x=1400\) makes it easy to compute the Z-score: \[\begin{eqnarray*}

Z = \frac{x - \mu}{\sigma} = \frac{1400 - 1500}{300} = -0.3333

\end{eqnarray*}\] Using the pnorm() function (either pnorm(-1/3) or pnorm(1400, m=1500, s=300) will give the desired result), the desired probability is \(0.3694\). Edward is at the \(37^{th}\) percentile.

Use the results of the previous example to compute the proportion of SAT takers who did better than Edward. Also draw a new picture.96

Areas to the right.

The pnorm() function (and the normal probability table in most books) gives the area to the left. If you would like the area to the right, first find the area to the left and then subtract this amount from one. In R, you can also do this by setting the lower.tail argument to FALSE.

Stuart earned an SAT score of 2100. Draw a picture for each part. (a) What is his percentile? (b) What percent of SAT takers did better than Stuart?97

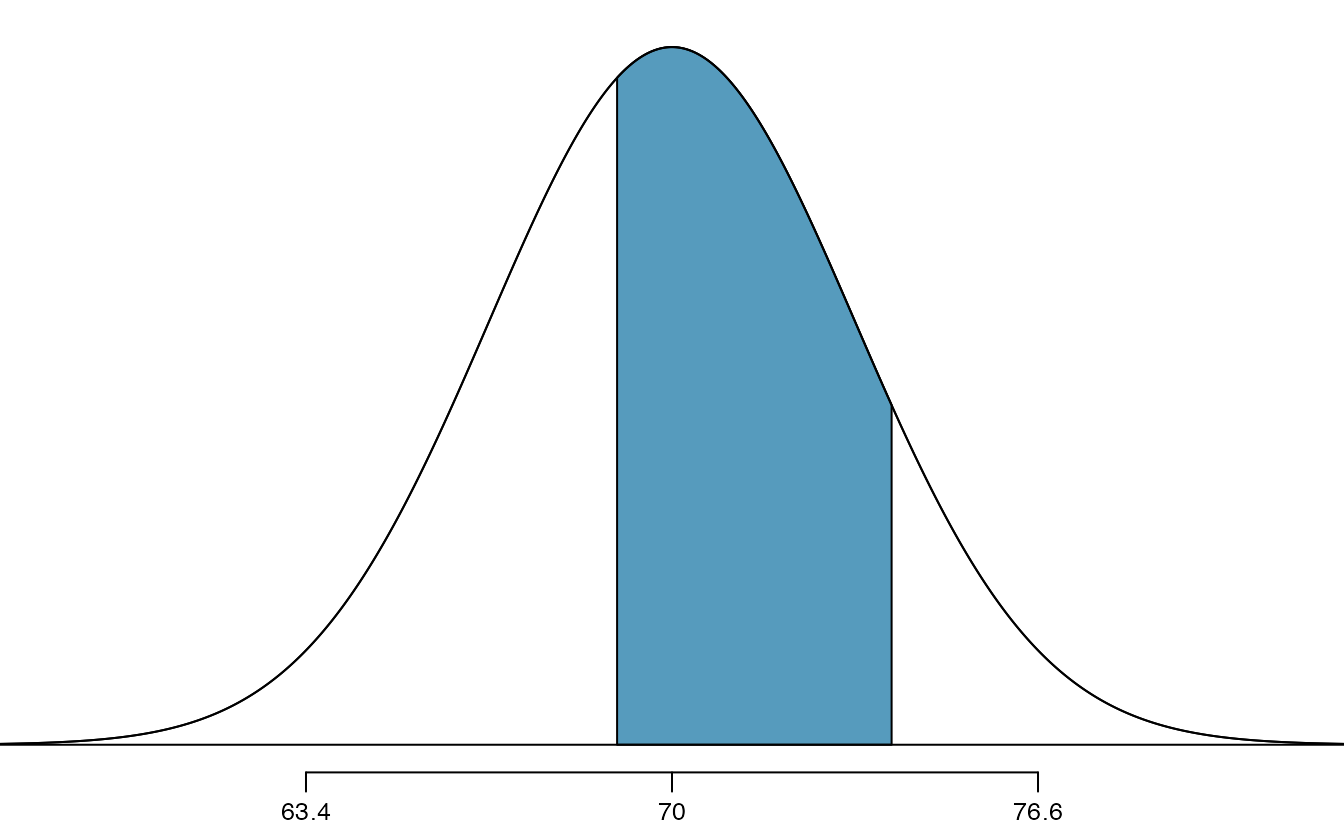

Based on a sample of 100 men,98 the heights of male adults between the ages 20 and 62 in the US is nearly normal with mean 70.0’’ and standard deviation 3.3’’.

Mike is 5’7’’ and Jim is 6’4’’. (a) What is Mike’s height percentile? (b) What is Jim’s height percentile? Also draw one picture for each part.99

The last several problems have focused on finding the probability or percentile for a particular observation. What if you would like to know the observation corresponding to a particular percentile?

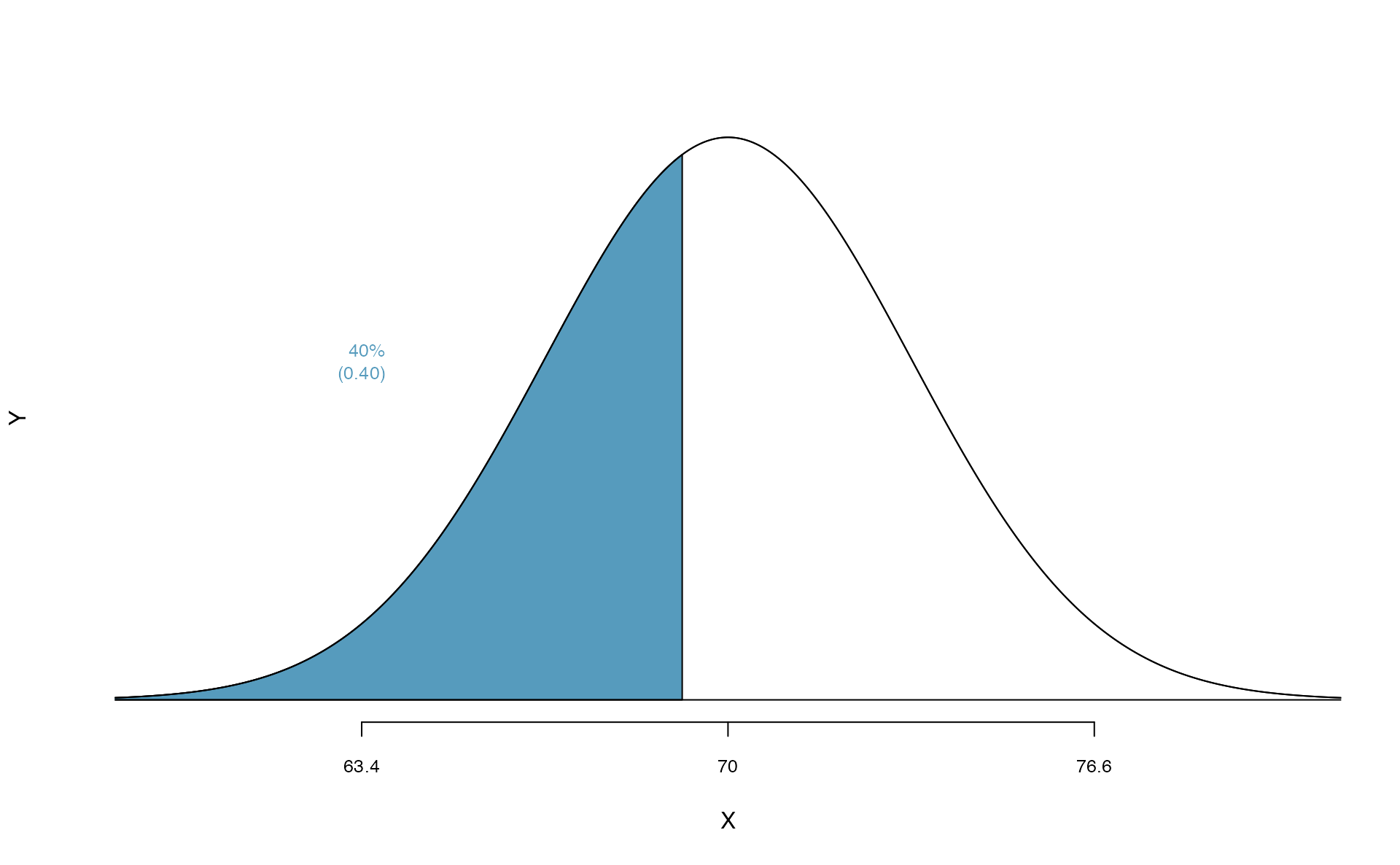

Erik’s height is at the \(40^{th}\) percentile. How tall is he?

As always, first draw the picture (see below).

In this case, the lower tail probability is known (0.40), which can be shaded on the diagram. We want to find the observation that corresponds to this value. As a first step in this direction, we determine the Z-score associated with the \(40^{th}\) percentile.

Because the percentile is below 50%, we know \(Z\) will be negative. Looking in the negative part of the normal probability table, we search for the probability inside the table closest to 0.4000. We find that 0.4000 falls in row \(-0.2\) and between columns \(0.05\) and \(0.06\). Since it falls closer to \(0.05\), we take this one: \(Z=-0.25\).

Knowing \(Z_{Erik}=-0.25\) and the population parameters \(\mu=70\) and \(\sigma=3.3\) inches, the Z-score formula can be set up to determine Erik’s unknown height, labeled \(x_{Erik}\): \[\begin{eqnarray*} -0.25 = Z_{Erik} = \frac{x_{Erik} - \mu}{\sigma} = \frac{x_{Erik} - 70}{3.3} \end{eqnarray*}\] Solving for \(x_{Erik}\) yields the height 69.18 inches. That is, Erik is about 5’9’’ (this is notation for 5-feet, 9-inches).

qnorm(0.4, m = 0, s = 1)

#> [1] -0.253

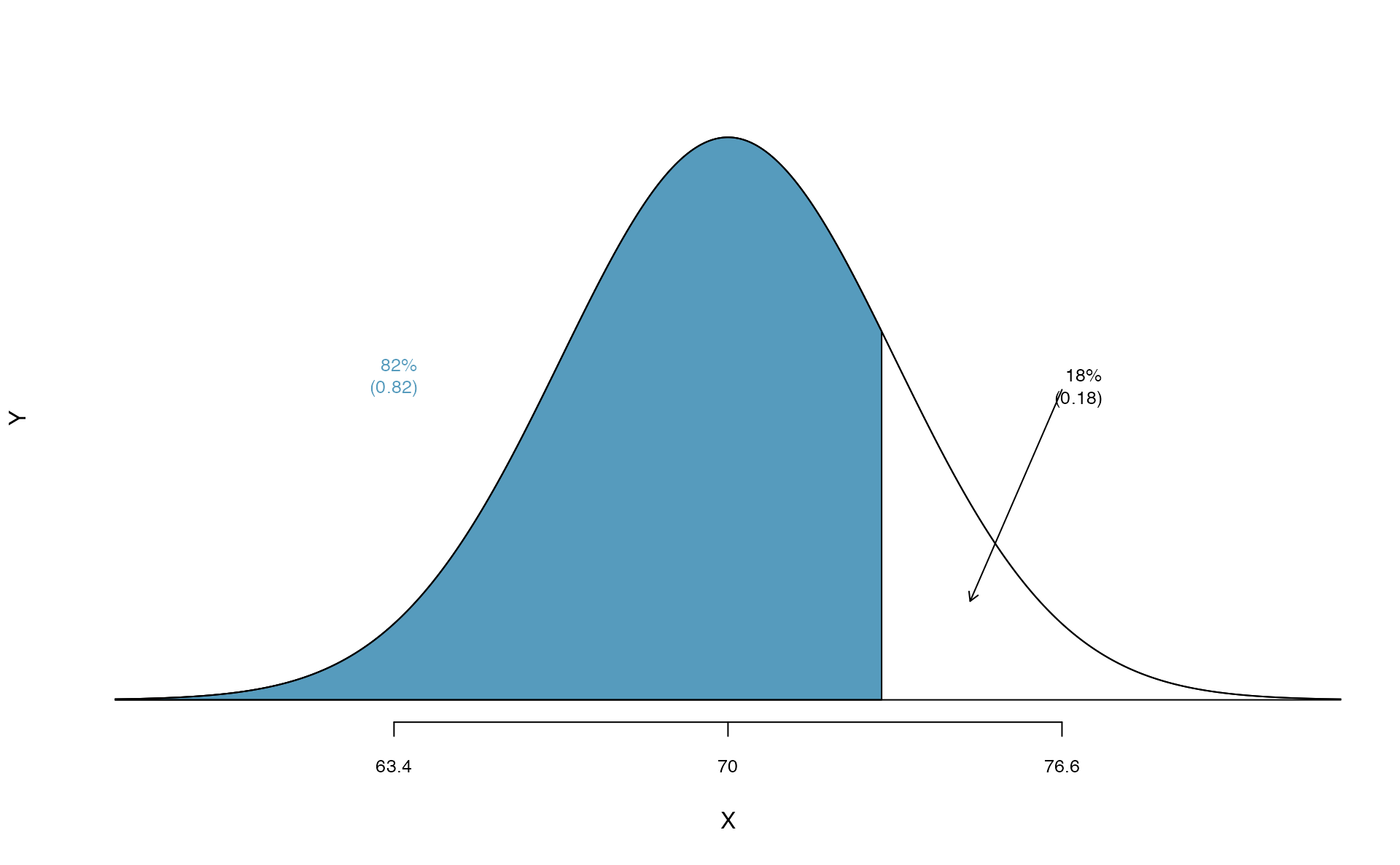

What is the adult male height at the \(82^{nd}\) percentile?

Again, we draw the figure first (see below).

Next, we want to find the Z-score at the \(82^{nd}\) percentile, which will be a positive value. Using qnorm(), the \(82^{nd}\) percentile corresponds to \(Z=0.92\). Finally, the height \(x\) is found using the Z-score formula with the known mean \(\mu\), standard deviation \(\sigma\), and Z-score \(Z=0.92\): \[\begin{eqnarray*}

0.92 = Z = \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} = \frac{x - 70}{3.3}

\end{eqnarray*}\] This yields 73.04 inches or about 6’1’’ as the height at the \(82^{nd}\) percentile.

qnorm(0.82, m = 0, s = 1)

#> [1] 0.915

- What is the \(95^{th}\) percentile for SAT scores?

- What is the \(97.5^{th}\) percentile of the male heights? As always with normal probability problems, first draw a picture.100

- What is the probability that a randomly selected male adult is at least 6’2’’ (74 inches)?

- What is the probability that a male adult is shorter than 5’9’’ (69 inches)?101

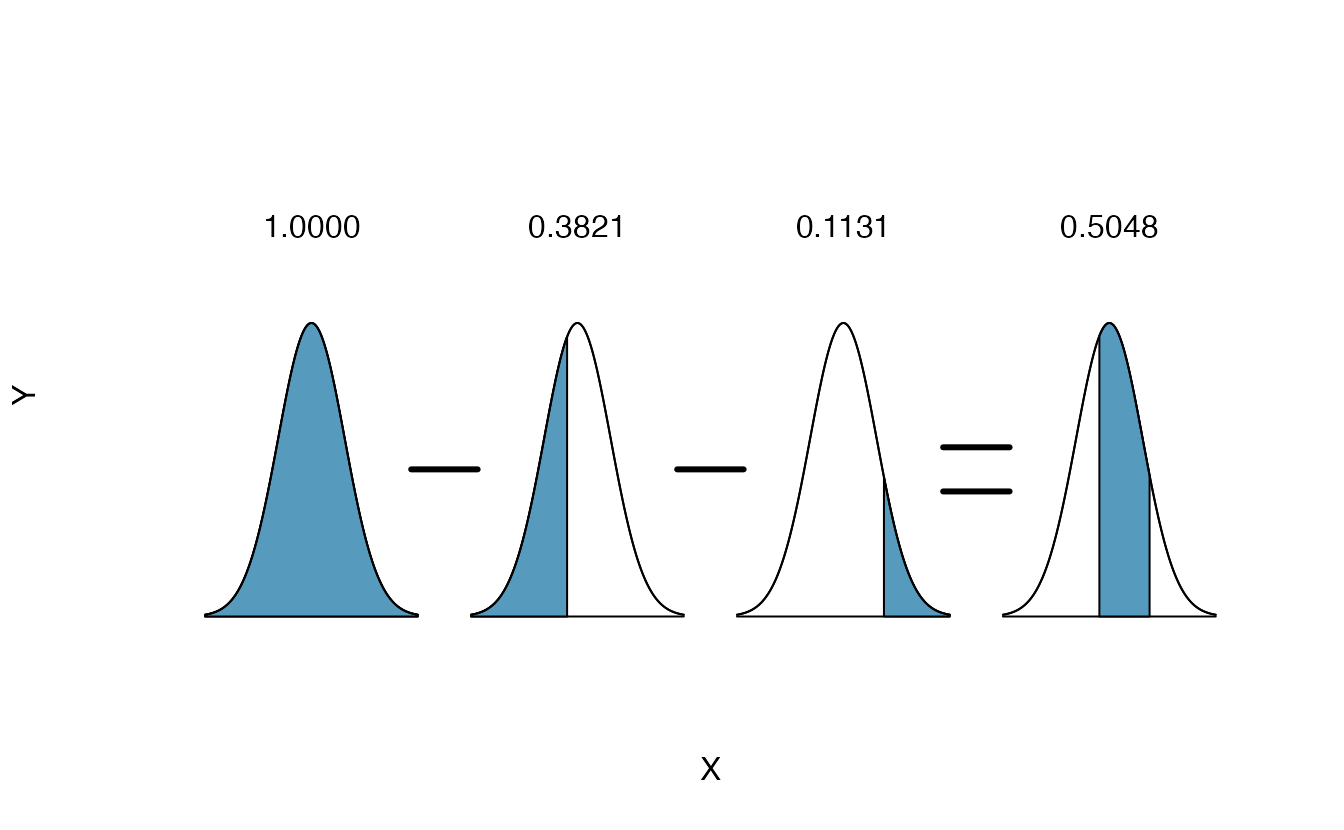

What is the probability that a random adult male is between 5’9’’ and 6’2’’?

These heights correspond to 69 inches and 74 inches. First, draw the figure. The area of interest is no longer an upper or lower tail.

The total area under the curve is 1. If we find the area of the two tails that are not shaded (from the previous Guided Practice, these areas are \(0.3821\) and \(0.1131\)), then we can find the middle area:

That is, the probability of being between 5’9’’ and 6’2’’ is 0.5048.

What percent of SAT takers get between 1500 and 2000?102

What percent of adult males are between 5’5’’ and 5’7’’?103

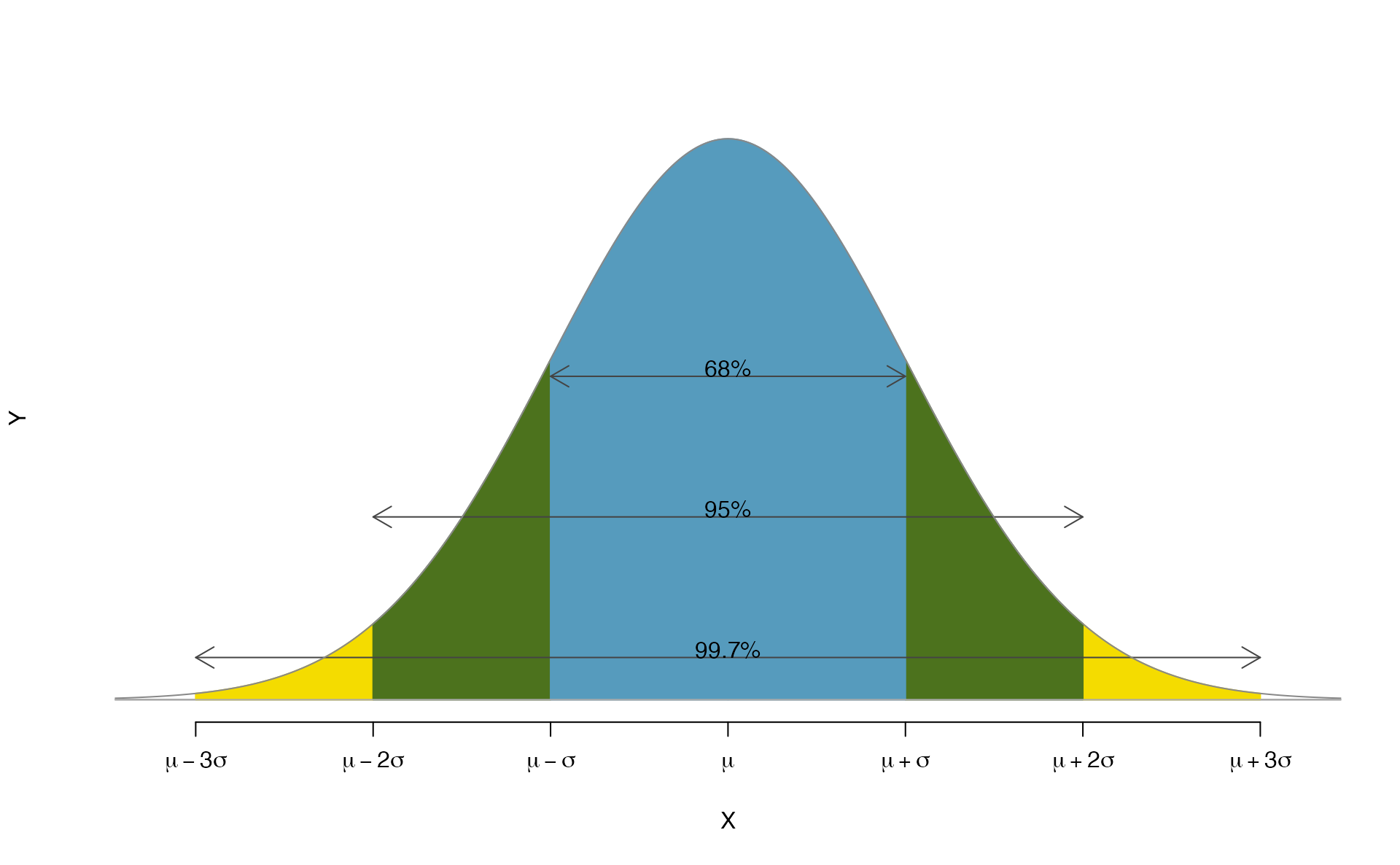

5.2.5 68-95-99.7 rule

Here, we present a useful general rule for the probability of falling within 1, 2, and 3 standard deviations of the mean in the normal distribution. The rule will be useful in a wide range of practical settings, especially when trying to make a quick estimate without a calculator or Z table.

Figure 5.9: Probabilities for falling within 1, 2, and 3 standard deviations of the mean in a normal distribution.

Use pnorm() to confirm that about 68%, 95%, and 99.7% of observations fall within 1, 2, and 3, standard deviations of the mean in the normal distribution, respectively. For instance, first find the area that falls between \(Z=-1\) and \(Z=1\), which should have an area of about 0.68. Similarly there should be an area of about 0.95 between \(Z=-2\) and \(Z=2\).104

It is possible for a normal random variable to fall 4, 5, or even more standard deviations from the mean. However, these occurrences are very rare if the data are nearly normal. The probability of being further than 4 standard deviations from the mean is about 1-in-30,000. For 5 and 6 standard deviations, it is about 1-in-3.5 million and 1-in-1 billion, respectively.

SAT scores closely follow the normal model with mean \(\mu = 1500\) and standard deviation \(\sigma = 300\).

(a) About what percent of test takers score 900 to 2100?

(b) What percent score between 1500 and 2100?105

5.3 One proportion

Notation.

- \(n\) = sample size (number of observational units in the data set)

- \(\hat{p}\) = sample proportion (number of “successes” divided by the sample size)

- \(\pi\) = population proportion106

A single proportion is used to summarize data when we measured a single categorical variable on each observational unit—the single variable is measured as either a success or failure (e.g., “surgical complication” vs. “no surgical complication”)107.

5.3.1 Simulation-based test for \(H_0: \pi = \pi_0\)

In Section 5.1.3, we introduced the general steps of a hypothesis test:

General steps of a hypothesis test. Every hypothesis test follows these same general steps:

- Frame the research question in terms of hypotheses.

- Collect and summarize data using a test statistic.

- Assume the null hypothesis is true, and simulate or mathematically model a null distribution for the test statistic.

- Compare the observed test statistic to the null distribution to calculate a p-value.

- Make a conclusion based on the p-value, and write a conclusion in context, in plain language, and in terms of the alternative hypothesis.

People providing an organ for donation sometimes seek the help of a special medical consultant. These consultants assist the patient in all aspects of the surgery, with the goal of reducing the possibility of complications during the medical procedure and recovery. Patients might choose a consultant based in part on the historical complication rate of the consultant’s clients.

One consultant tried to attract patients by noting the average complication rate for liver donor surgeries in the US is about 10%, but her clients have had only 3 complications in the 62 liver donor surgeries she has facilitated. She claims this is strong evidence that her work meaningfully contributes to reducing complications (and therefore she should be hired!).

Using these data, is it possible to assess the consultant’s claim that her work meaningfully contributes to reducing complications?

No. The claim is that there is a causal connection, but the data are observational, so we must be on the lookout for confounding variables. For example, maybe patients who can afford a medical consultant can afford better medical care, which can also lead to a lower complication rate.

While it is not possible to assess the causal claim, it is still possible to understand the consultant’s true rate of complications.

Steps 1 and 2: Hypotheses and test statistic

Regardless of if we use simulation-based methods or theory-based methods, the first two steps of a hypothesis test start out the same: setting up hypotheses and summarizing data with a test statistic. We will let \(\pi\) represent the true complication rate for liver donors working with this consultant. This “true” complication probability is called the parameter of interest108. The sample proportion for the complication rate is 3 complications divided by the 62 surgeries the consultant has worked on: \(\hat{p} = 3/62 = 0.048\). Since this value is estimated from sample data, it is called a statistic. The statistic \(\hat{p}\) is also our point estimate, or “best guess,” for \(\pi\), and we will use is as our test statistic.

Parameters and statistics.

A parameter is the “true” value of interest. We typically estimate the parameter using a statistic from a sample of data. When a statistic is used as an estimate of a parameter, it is called a point estimate.

For example, we estimate the probability \(\pi\) of a complication for a client of the medical consultant by examining the past complications rates of her clients:

\[\hat{p} = 3 / 62 = 0.048\qquad\text{is used to estimate}\qquad \pi\]

Summary measures that summarize a sample of data, such as \(\hat{p}\), are called statistics. Numbers that summarize an entire population, such as \(\pi\), are called parameters. You can remember this distinction by looking at the first letter of each term:

Statistics summarize Samples.

Parameters summarize Populations.

We typically use Roman letters to symbolize statistics (e.g., \(\bar{x}\), \(\hat{p}\)), and Greek letters to symbolize parameters (e.g., \(\mu\), \(\pi\)). Since we rarely can measure the entire population, and thus rarely know the actual parameter values, we like to say, “We don’t know Greek, and we don’t know parameters!”

Write out hypotheses in both plain and statistical language to test for the association between the consultant’s work and the true complication rate, \(\pi\), for the consultant’s clients.

In words:

\(H_0\): There is no association between the consultant’s contributions and the clients’ complication rate.

\(H_A\): Patients who work with the consultant tend to have a complication rate lower than 10%.

In statistical language:

\(H_0: \pi=0.10\)

\(H_A: \pi<0.10\)

Steps 3 and 4: Null distribution and p-value

To assess these hypotheses, we need to evaluate the possibility of getting a sample proportion as far below the null value, \(0.10\), as what was observed (\(0.048\)), if the null hypothesis were true.

Null value of a hypothesis test.

The null value is the reference value for the parameter in \(H_0\), and it is sometimes represented with the parameter’s label with a subscript 0 (or “null”), e.g., \(\pi_0\) (just like \(H_0\)).

The deviation of the sample statistic from the null hypothesized parameter is usually quantified with a p-value109. The p-value is computed based on the null distribution, which is the distribution of the test statistic if the null hypothesis is true. Supposing the null hypothesis is true, we can compute the p-value by identifying the chance of observing a test statistic that favors the alternative hypothesis at least as strongly as the observed test statistic.

Null distribution.

The null distribution of a test statistic is the sampling distribution of that statistic under the assumption of the null hypothesis. It describes how that statistic would vary from sample to sample, if the null hypothesis were true.

The null distribution can be estimated through simulation (simulation-based methods), as in this section, or can be modeled by a mathematical function (theory-based methods), as in Section 5.3.4.

We want to identify the sampling distribution of the test statistic (\(\hat{p}\)) if the null hypothesis was true. In other words, we want to see how the sample proportion changes due to chance alone. Then we plan to use this information to decide whether there is enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

Under the null hypothesis, 10% of liver donors have complications during or after surgery. Suppose this rate was really no different for the consultant’s clients (for all the consultant’s clients, not just the 62 previously measured). If this was the case, we could simulate 62 clients to get a sample proportion for the complication rate from the null distribution.

This is a similar scenario to the one we encountered in Section 5.1.1, with one important difference—the null value is 0.10, not 0.50. Thus, flipping a coin to simulate whether a client had complications would not be simulating under the correct null hypothesis.

What physical object could you use to simulate a random sample of 62 clients who had a 10% chance of complications? How would you use this object?110

Assuming the true complication rate for the consultant’s clients is 10%, each client can be simulated using a bag of marbles with 10% red marbles and 90% white marbles. Sampling a marble from the bag (with 10% red marbles) is one way of simulating whether a patient has a complication if the true complication rate is 10% for the data. If we select 62 marbles and then compute the proportion of patients with complications in the simulation, \(\hat{p}_{sim}\), then the resulting sample proportion is calculated exactly from a sample from the null distribution.

An undergraduate student was paid $2 to complete this simulation. There were 5 simulated cases with a complication and 57 simulated cases without a complication, i.e., \(\hat{p}_{sim} = 5/62 = 0.081\).

Is this one simulation enough to determine whether or not we should reject the null hypothesis?

No. To assess the hypotheses, we need to see a distribution of many \(\hat{p}_{sim}\), not just a single draw from this sampling distribution.

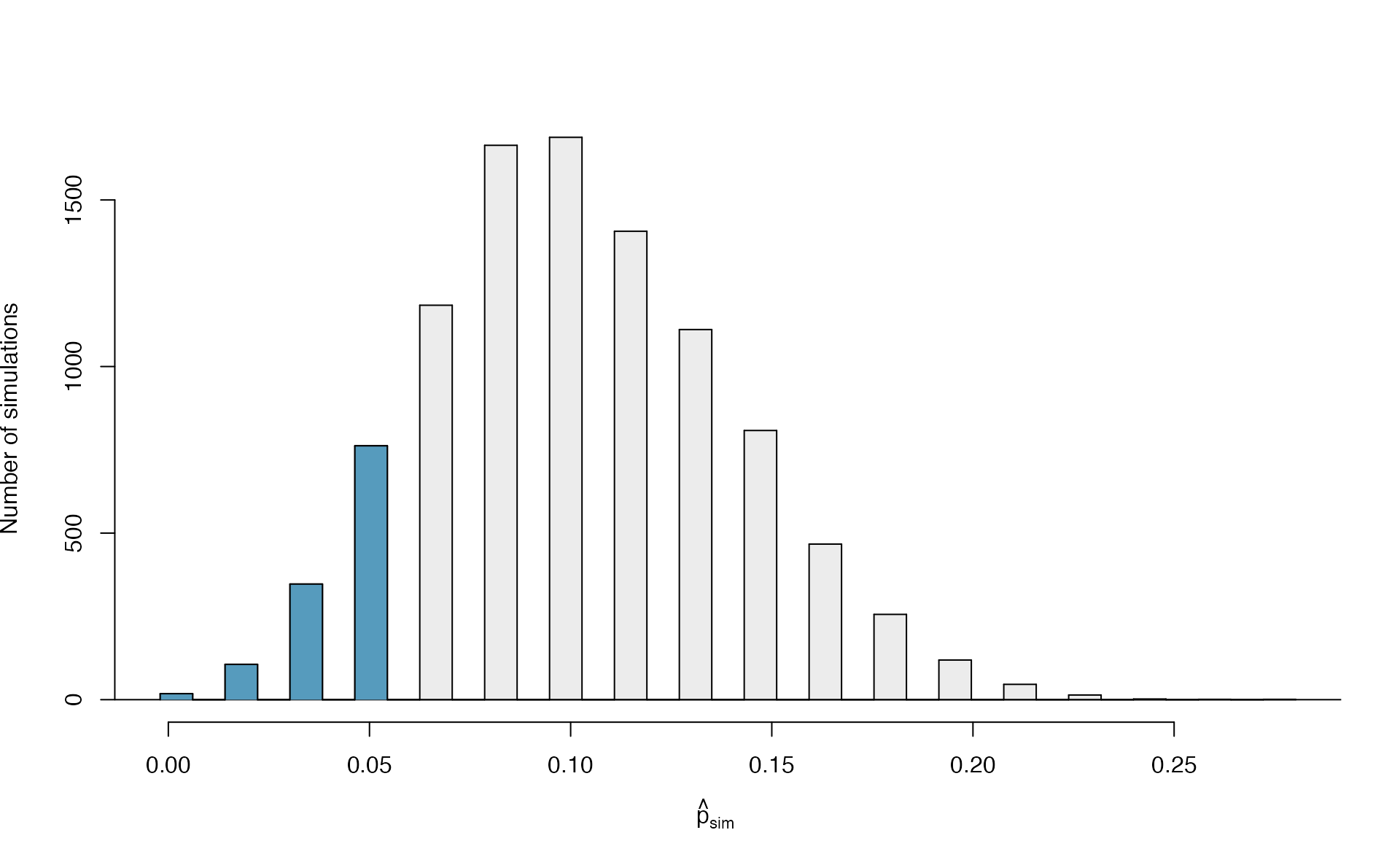

One simulation isn’t enough to get a sense of the null distribution; many simulation studies are needed. Roughly 10,000 seems sufficient. However, paying someone to simulate 10,000 studies by hand is a waste of time and money. Instead, simulations are typically programmed into a computer, which is much more efficient.

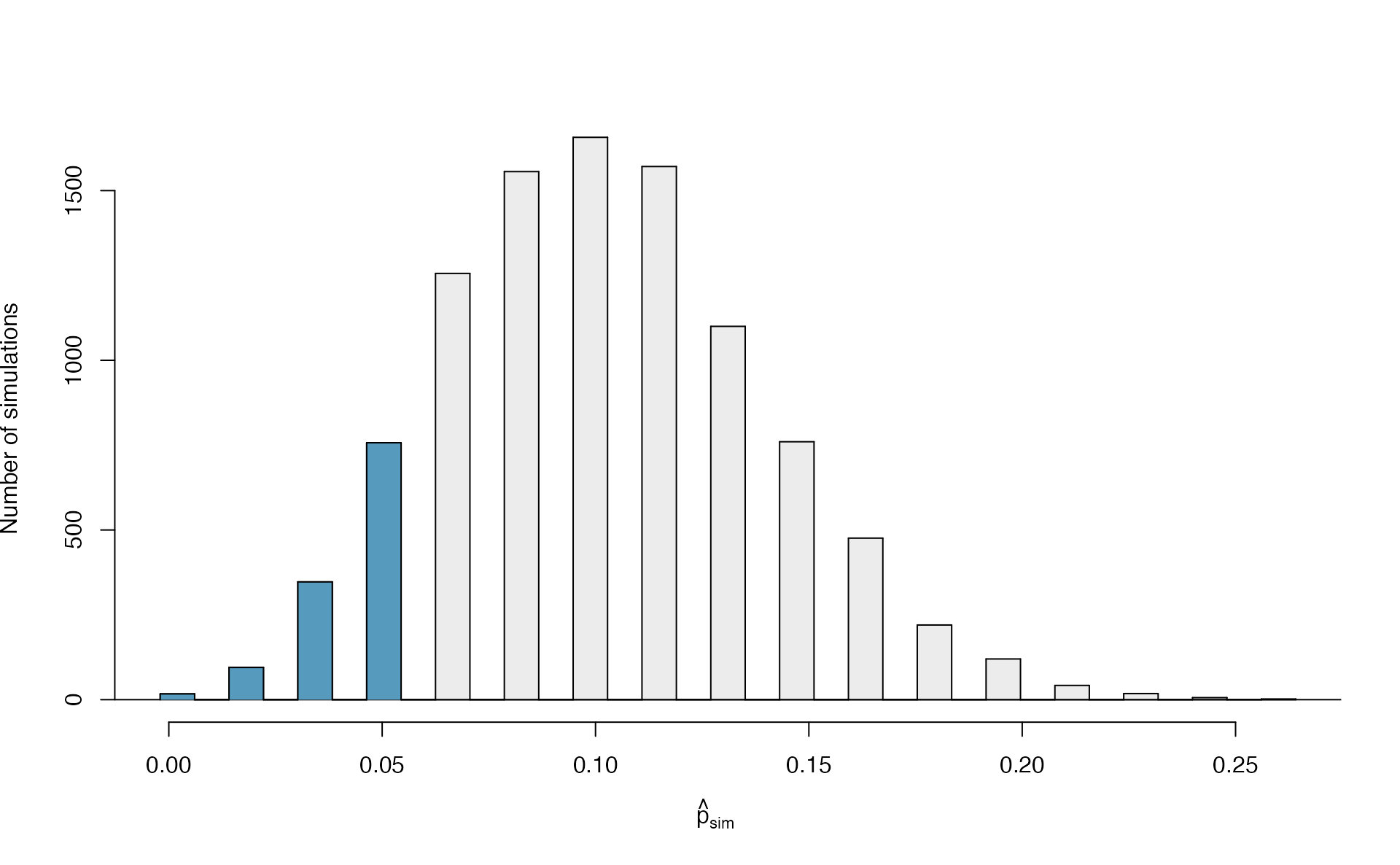

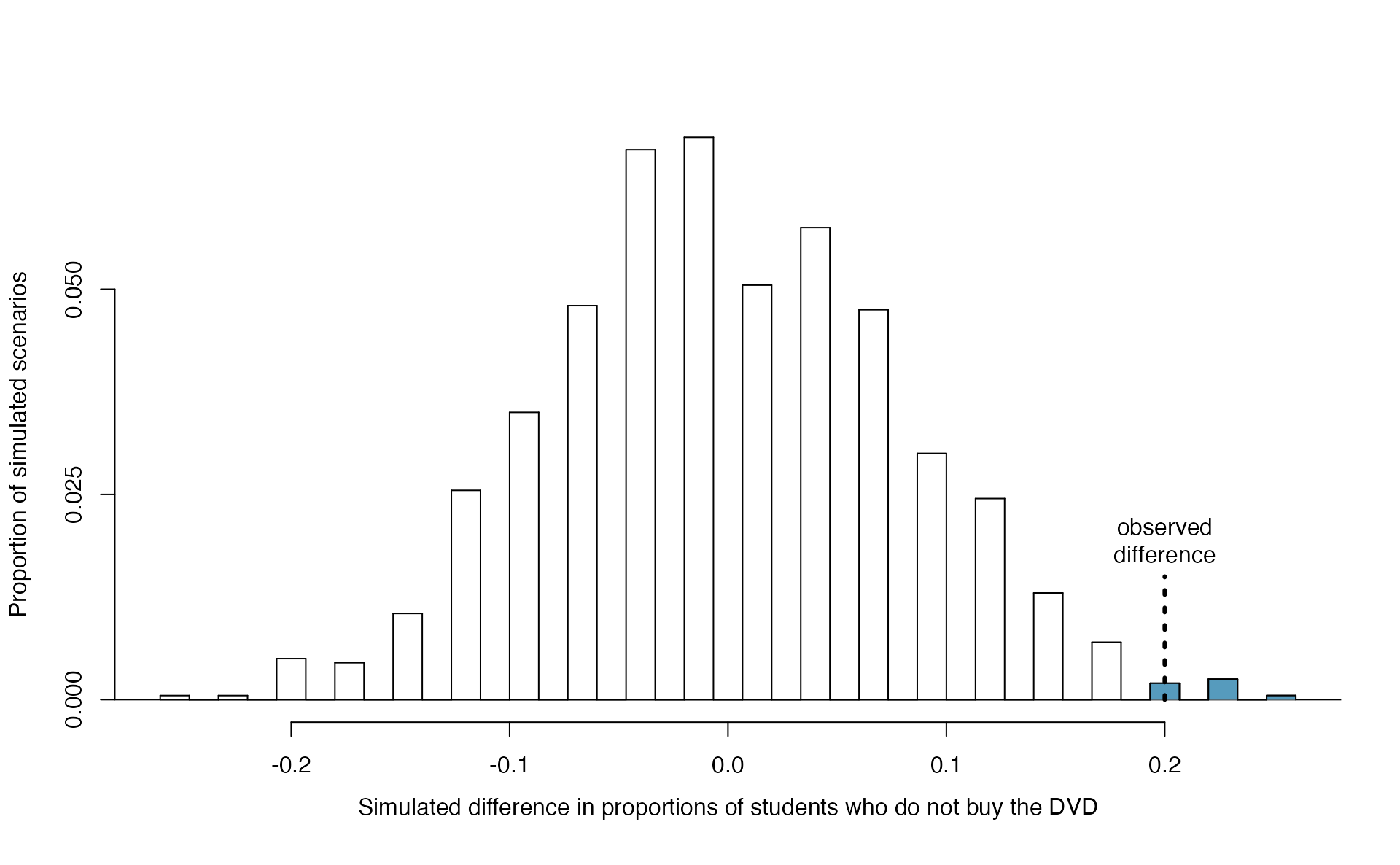

Figure 5.10 shows the results of 10,000 simulated studies. The proportions that are equal to or less than \(\hat{p}=0.048\) are shaded. The shaded areas represent sample proportions under the null distribution that provide at least as much evidence as \(\hat{p}\) favoring the alternative hypothesis. There were 1222 simulated sample proportions with \(\hat{p}_{sim} \leq 0.048\). We use these to construct the null distribution’s left-tail area and find the p-value: \[\begin{align} \text{left tail area }\label{estOfPValueBasedOnSimulatedNullForSingleProportion} &= \frac{\text{Number of observed simulations with }\hat{p}_{sim}\leq\text{ 0.048}}{10000} \end{align}\] Of the 10,000 simulated \(\hat{p}_{sim}\), 1222 were equal to or smaller than \(\hat{p}\). Since the hypothesis test is one-sided, the estimated p-value is equal to this tail area: 0.1222.

Figure 5.10: The null distribution for \(\hat{p}\), created from 10,000 simulated studies. The left tail, representing the p-value for the hypothesis test, contains 12.22% of the simulations.

Step 5: Conclusion

Because the estimated p-value is 0.1222, which is not small, we have little to no evidence against the null hypothesis. Explain what this means in plain language in the context of the problem.111

Does the conclusion in the previous Guided Practice imply there is no real association between the surgical consultant’s work and the risk of complications? Explain.112

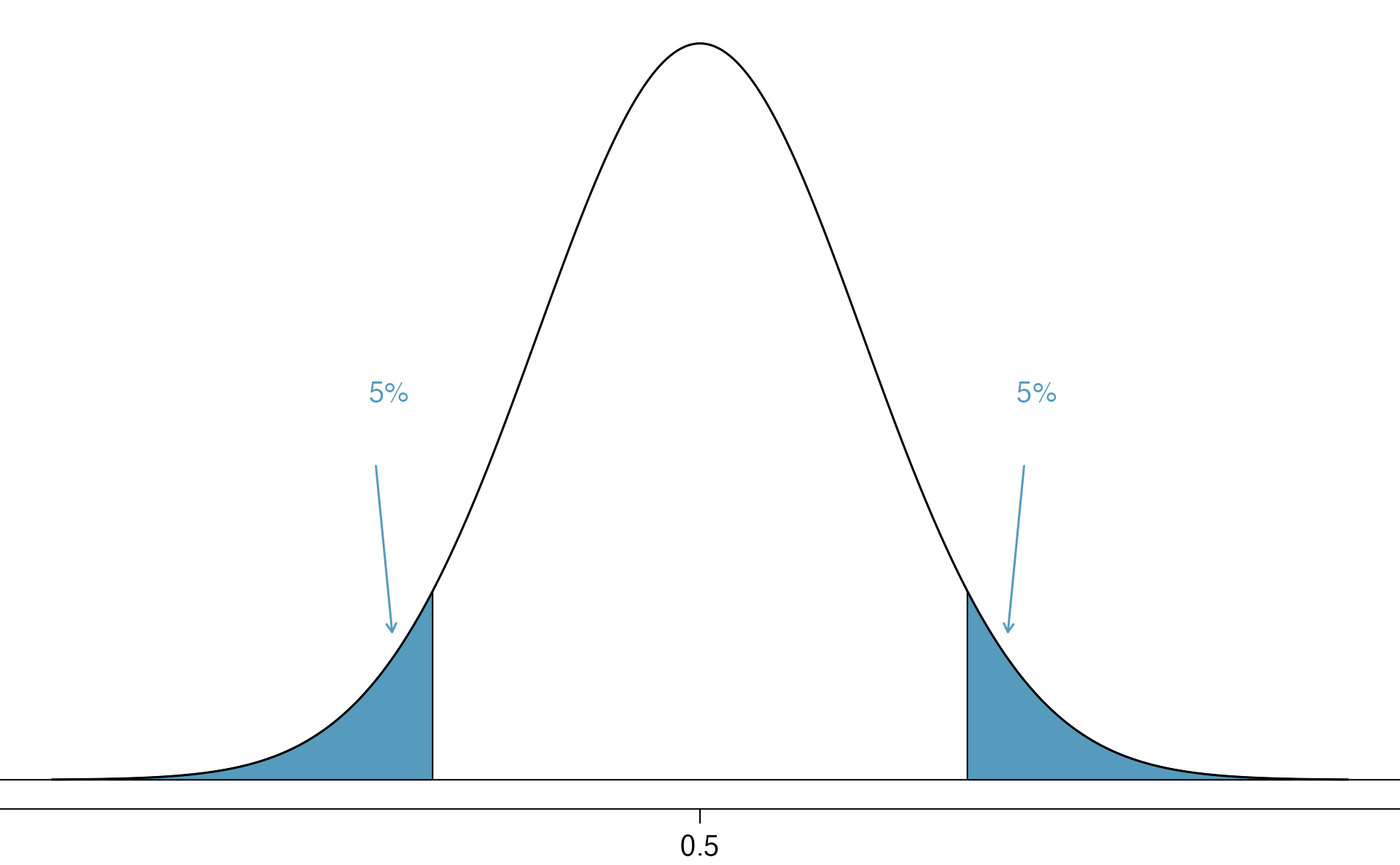

5.3.2 Two-sided hypotheses

Consider the situation of the medical consultant. The setting has been framed in the context of the consultant being helpful (which is what led us to consider whether the consultant’s patients had a complication rate below 10%). This original hypothesis is called a one-sided hypothesis test because it only explored one direction of possibilities.

But what if the consultant actually performed worse than the average? Would we care? More than ever! Since it turns out that we care about a finding in either direction, we should run a two-sided hypothesis test.

Form hypotheses for this study in plain and statistical language. Let \(\pi\) represent the true complication rate of organ donors who work with this medical consultant.

We want to understand whether the medical consultant is helpful or harmful. We’ll consider both of these possibilities using a two-sided hypothesis test.

\(H_0\): There is no association between the consultant’s contributions and the clients’ complication rate, i.e., \(\pi = 0.10\)

\(H_A\): There is an association, either positive or negative, between the consultant’s contributions and the clients’ complication rate, i.e., \(\pi \neq 0.10\).

Compare this to the one-sided hypothesis test, when the hypotheses were:

\(H_0\): There is no association between the consultant’s contributions and the clients’ complication rate, i.e., \(\pi = 0.10\).

\(H_A\): Patients who work with the consultant tend to have a complication rate lower than 10%, i.e., \(\pi < 0.10\).

There were 62 patients who worked with this medical consultant, 3 of which developed complications from their organ donation, for a point estimate of \(\hat{p} = \frac{3}{62} = 0.048\).

According to the point estimate, the complication rate for clients of this medical consultant is 5.2% below the expected complication rate of 10%. However, we wonder if this difference could be easily explainable by chance.

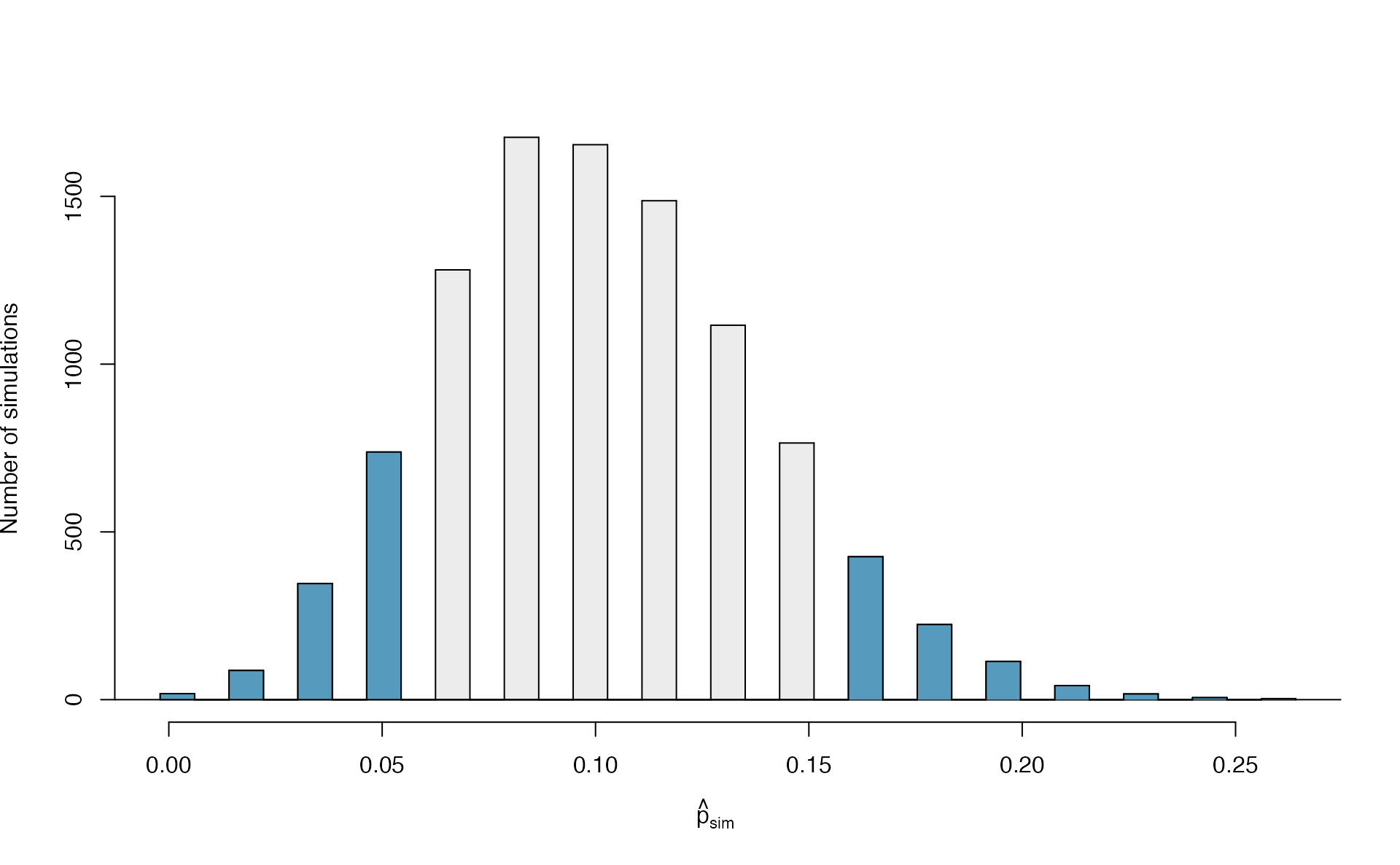

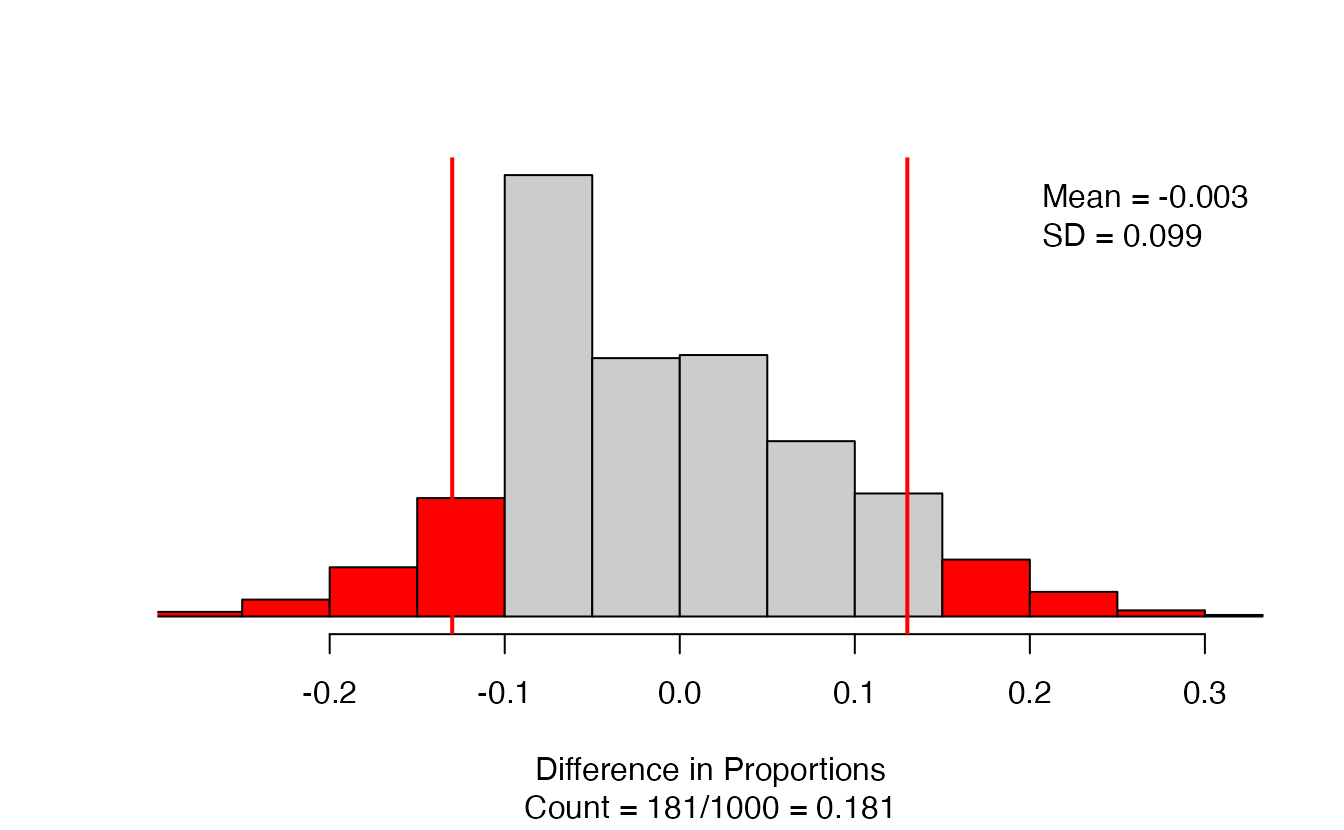

Recall previously in this chapter, we simulated what proportions we might see from chance alone under the null hypothesis. By using marbles, cards, or a spinner to reflect the null hypothesis, we can simulate what would happen to 62 ‘patients’ if the true complication rate is 10%. After repeating this simulation 10,000 times, we can build a null distribution of the sample proportions shown in Figure 5.11.

Figure 5.11: The null distribution for \(\hat{p}\), created from 10,000 simulated studies.

The original hypothesis, investigating if the medical consultant was helpful, was a one-sided hypothesis test (\(H_A: \pi < 0.10\)) so we only counted the simulations below our observed proportion of 0.048 in order to calculate the p-value of 0.1222 or 12.22%. However, the p-value of this two-sided hypothesis test investigating if the medical consultant is helpful or harmful is not 0.1222!

The p-value is defined as the chance we observe a result at least as favorable to the alternative hypothesis as the result (i.e., the proportion) we observe. For a two-sided hypothesis test, that means finding the proportion of simulations further in either tail than the observed result, or beyond a point that is equi-distant from the null hypothesis as the observed result.

In this case, the observed proportion of 0.048 is 0.052 below the null hypothesized value of 0.10. So while we will continue to count the 0.1222 simulations at or below 0.048, we must add to that the proportion of simulations that are at or above \(0.10 + 0.052 = 0.152\) in order to obtain the p-value.

In Figure 5.12 we’ve also shaded these differences in the right tail of the distribution. These two shaded tails provide a visual representation of the p-value for a two-sided test.

Figure 5.12: The null distribution for \(\hat{p}\), created from 10,000 simulated studies. All simulations that are at least as far from the null value of 0.10 as the observed proportion (i.e., those below 0.048 and those above 0.152) are shaded.

From our previous simulation, we know that 12.22% of the simulations lie at or below the observed proportion of 0.048. Figure 5.12 shows that an additional 0.0811 or 8.11% of simulations fall at or above 0.152. This indicates the p-value for this two-sided test is \(0.1222 + 0.0811 = 0.2033\). With this large p-value, we do not find statistically significant evidence that the medical consultant’s patients had a complication rate different from 10%.

In Section 5.3.4, you will learn that the null distribution will be symmetric under certain conditions. When the null distribution is symmetric, we can find a two-sided p-value by merely taking the single tail (in this case, 0.1222) and double it to get the two-sided p-value: 0.2444. Note that the example here does not satisfy the conditions and the null distribution in Figure 5.12 is not symmetric. This results in the ‘doubled’ p-value of 0.2444 not being a good estimate of the calculated two-sided p-value of 0.2033.

Default to a two-sided test.

We want to be rigorous and keep an open mind when we analyze data and evidence. Use a one-sided hypothesis test only if you truly have interest in only one direction.

Computing a p-value for a two-sided test.

If your null distribution is symmetric, first compute the p-value for one tail of the distribution, then double that value to get the two-sided p-value. That’s it!113

Generally, to find a two-sided p-value we double the single tail area, which remains a reasonable approach even when the sampling distribution is asymmetric. However, the approach can result in p-values larger than 1 when the point estimate is very near the mean in the null distribution; in such cases, we write that the p-value is 1. Also, very large p-values computed in this way (e.g. 0.85), may also be slightly inflated. Typically, we do not worry too much about the precision of very large p-values because they lead to the same analysis conclusion, even if the value is slightly off.

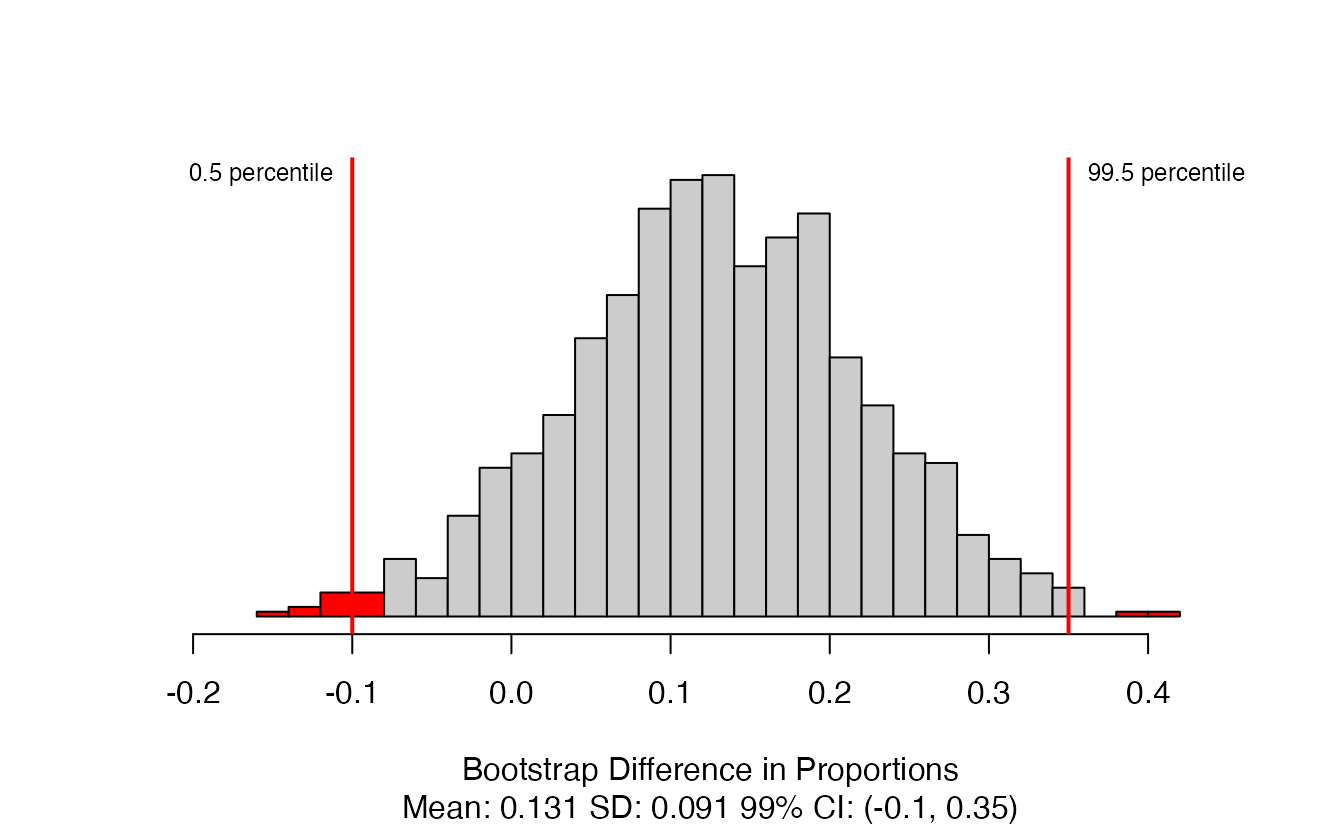

5.3.3 Bootstrap confidence interval for \(\pi\)

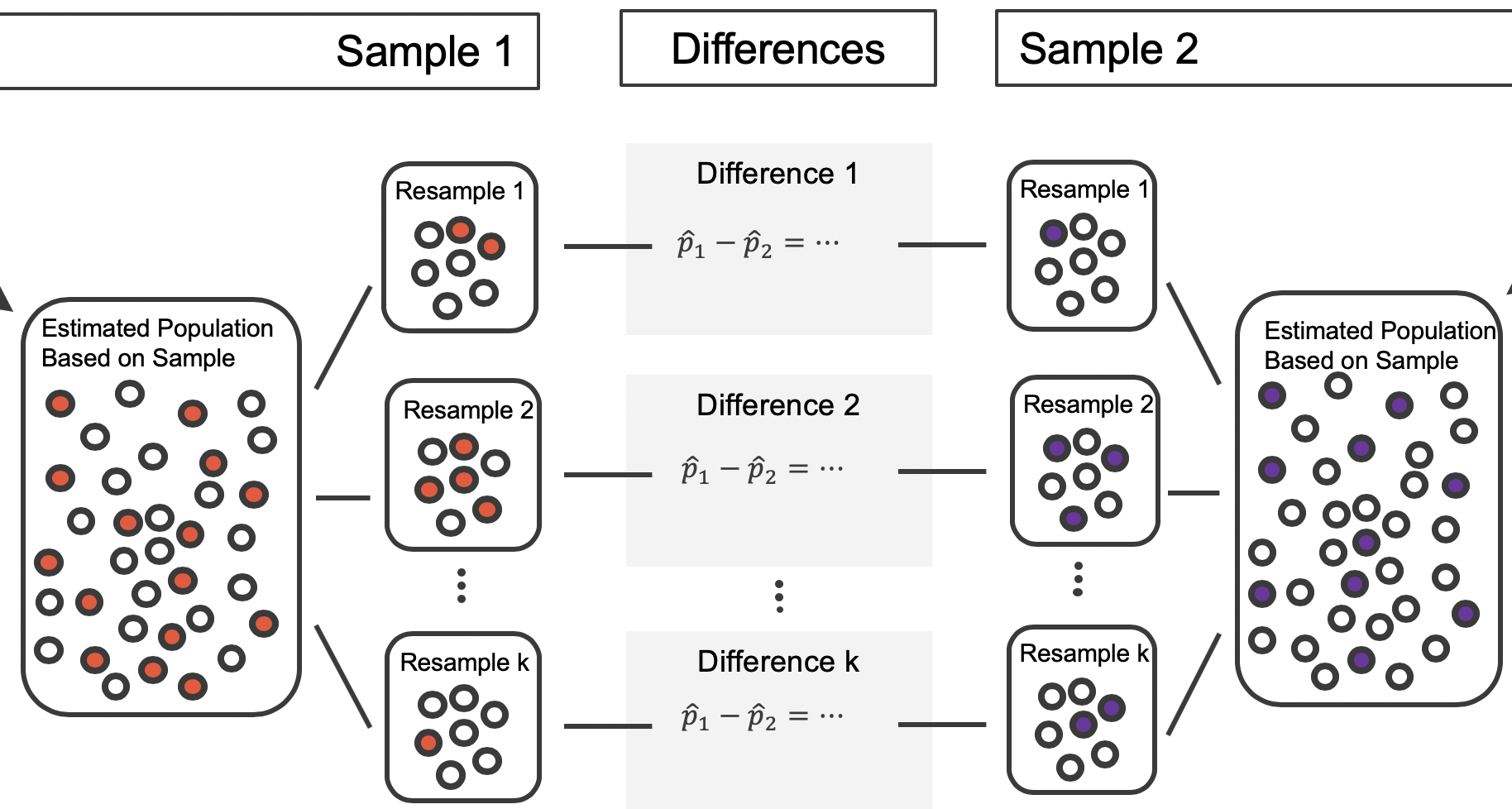

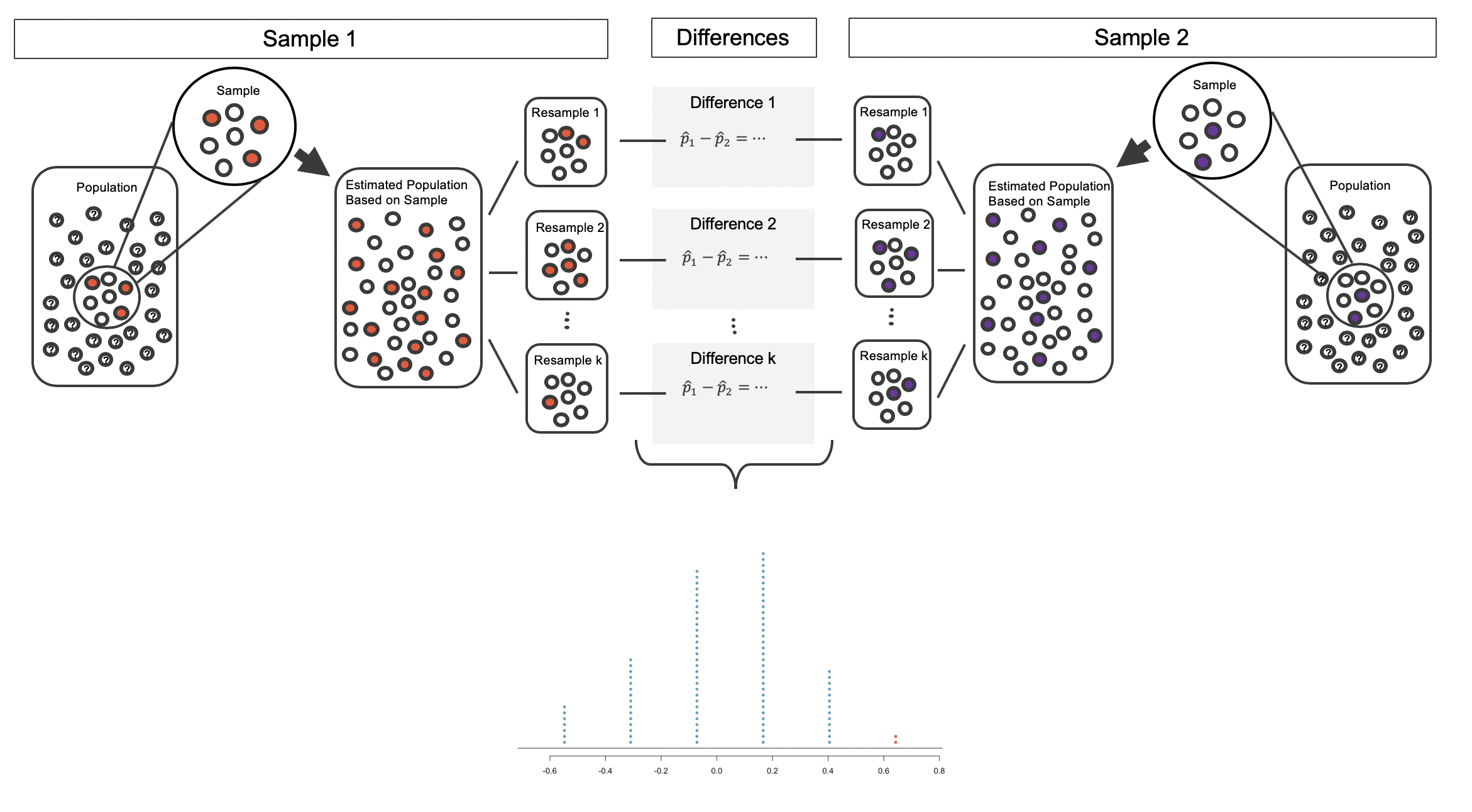

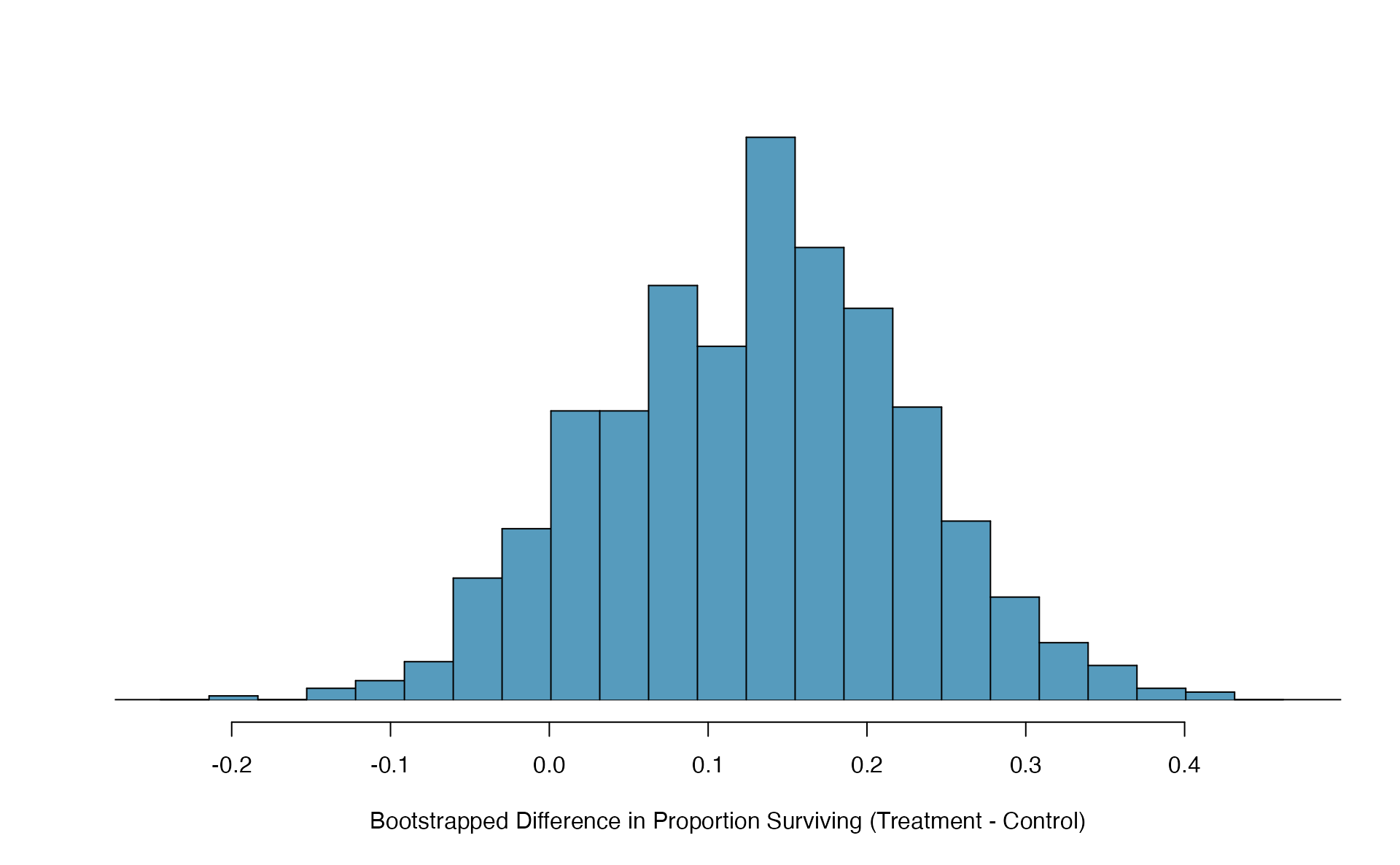

A confidence interval provides a range of plausible values for the parameter \(\pi\). If the goal is to produce a range of possible values for a population value, then in an ideal world, we would sample data from the population again and recompute the sample proportion. Then we could do it again. And again. And so on until we have a good sense of the variability of our original estimate. The ideal world where sampling data is free or extremely cheap is almost never the case, and taking repeated samples from a population is usually impossible. So, instead of using a “resample from the population” approach, bootstrapping uses a “resample from the sample” approach.

Let’s revisit our medical consultant example from Section 5.3.1. This consultant tried to attract patients by noting the average complication rate for liver donor surgeries in the US is about 10%, but her clients have had only 3 complications in the 62 liver donor surgeries she has facilitated. This data, however, did not provide sufficient evidence that the consultant’s complication rate was less than 10%, since the p-value was approximately 0.122. Does this mean we can conclude that the consultant’s complication rate was equal to 10%?

No! Though our decision was to fail to reject the null hypothesis, this does not mean we have evidence for the null hypothesis—we cannot “accept” the null. The sample proportion was \(\hat{p} = 3/62 = 0.048\), which is our point estimate—or “best guess”—of \(\pi\). It wouldn’t make sense that a sample complication rate of 4.8% gives us evidence that the true complication rate was exactly 10%. It’s plausible that the true complication rate is 10%, but there are a range of plausible values for \(\pi\). In this section, we will use a simulation-based method called bootstrapping to generate this range of plausible values for \(\pi\) using the observed data.

In the medical consultant case study, the parameter is \(\pi\), the true probability of a complication for a client of the medical consultant. There is no reason to believe that \(\pi\) is exactly \(\hat{p} = 3/62\), but there is also no reason to believe that \(\pi\) is particularly far from \(\hat{p} = 3/62\). By sampling with replacement from the data set (a process called bootstrapping),114 the variability of the possible \(\hat{p}\) values can be approximated, which will allow us to generate a range of plausible values for \(\pi\), i.e., a confidence interval.

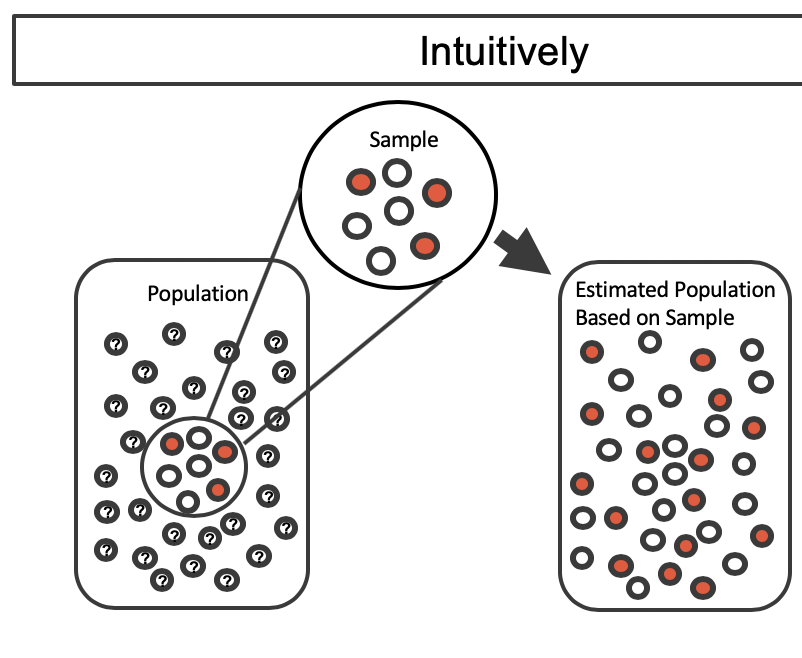

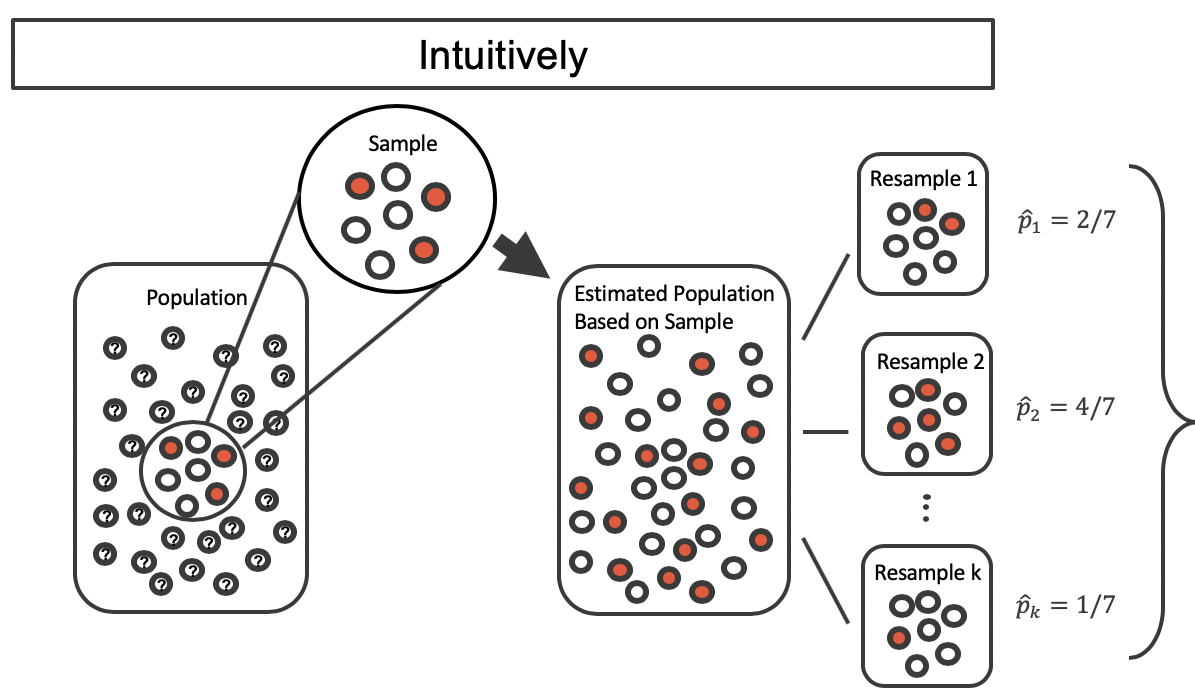

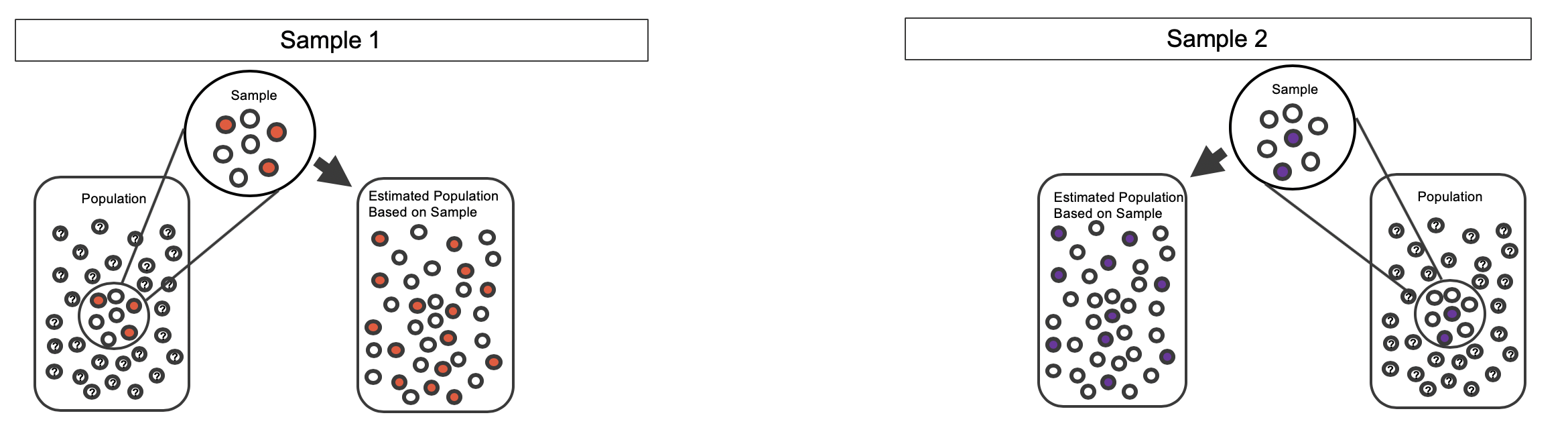

Most of the inferential procedures covered in this text are grounded in quantifying how one data set would differ from another when they are both taken from the same population. It doesn’t make sense to take repeated samples from the same population because if you have the means to take more samples, a larger sample size will benefit you more than the exact same sample twice. Instead, we measure how the samples behave under an estimate of the population. Figure 5.13 shows how an unknown original population of red and white marbles can be estimated by using multiple copies of a sample of seven marbles.

Figure 5.13: An unknown population of red and white marbles. The estimated population on the right is many copies of the observed sample.

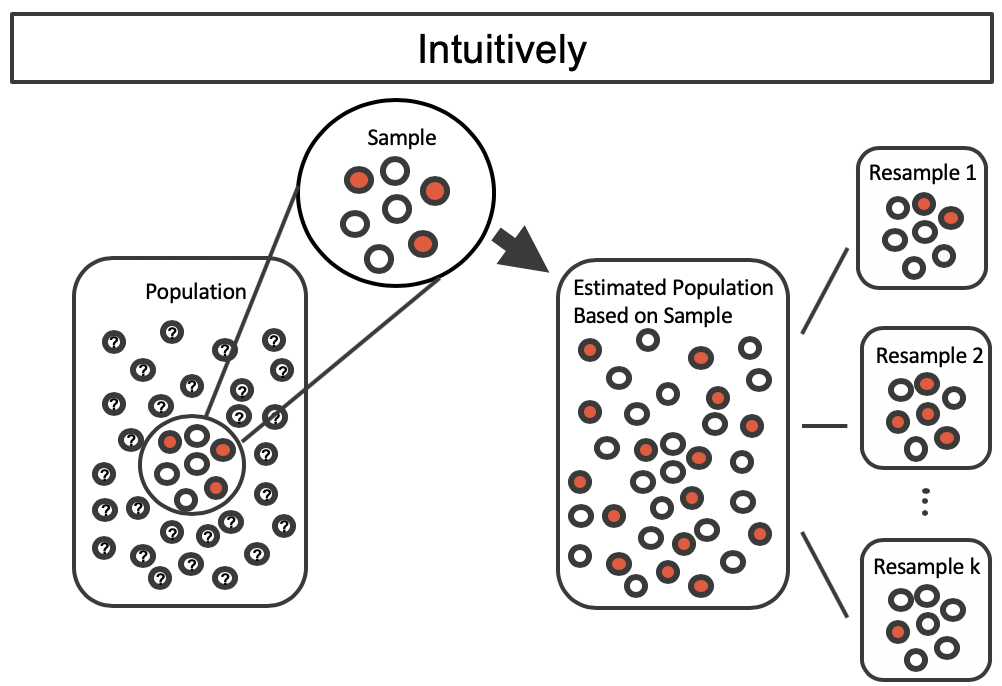

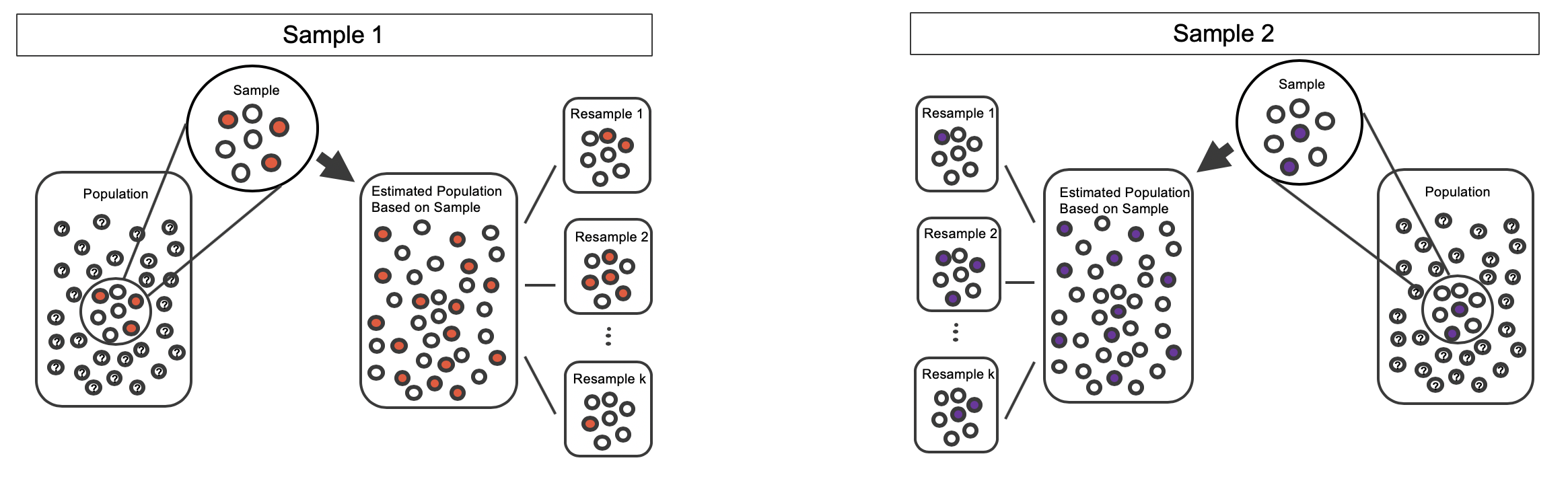

By taking repeated samples from the estimated population, the variability from sample to sample can be observed. In Figure 5.14 the repeated bootstrap samples are obviously different both from each other, from the original sample, and from the original population. Recall that the bootstrap samples were taken from the same (estimated) population, and so the differences are due entirely to natural variability in the sampling procedure.

Figure 5.14: Selecting \(k\) random samples from the estimated population created from copies of the observed sample.

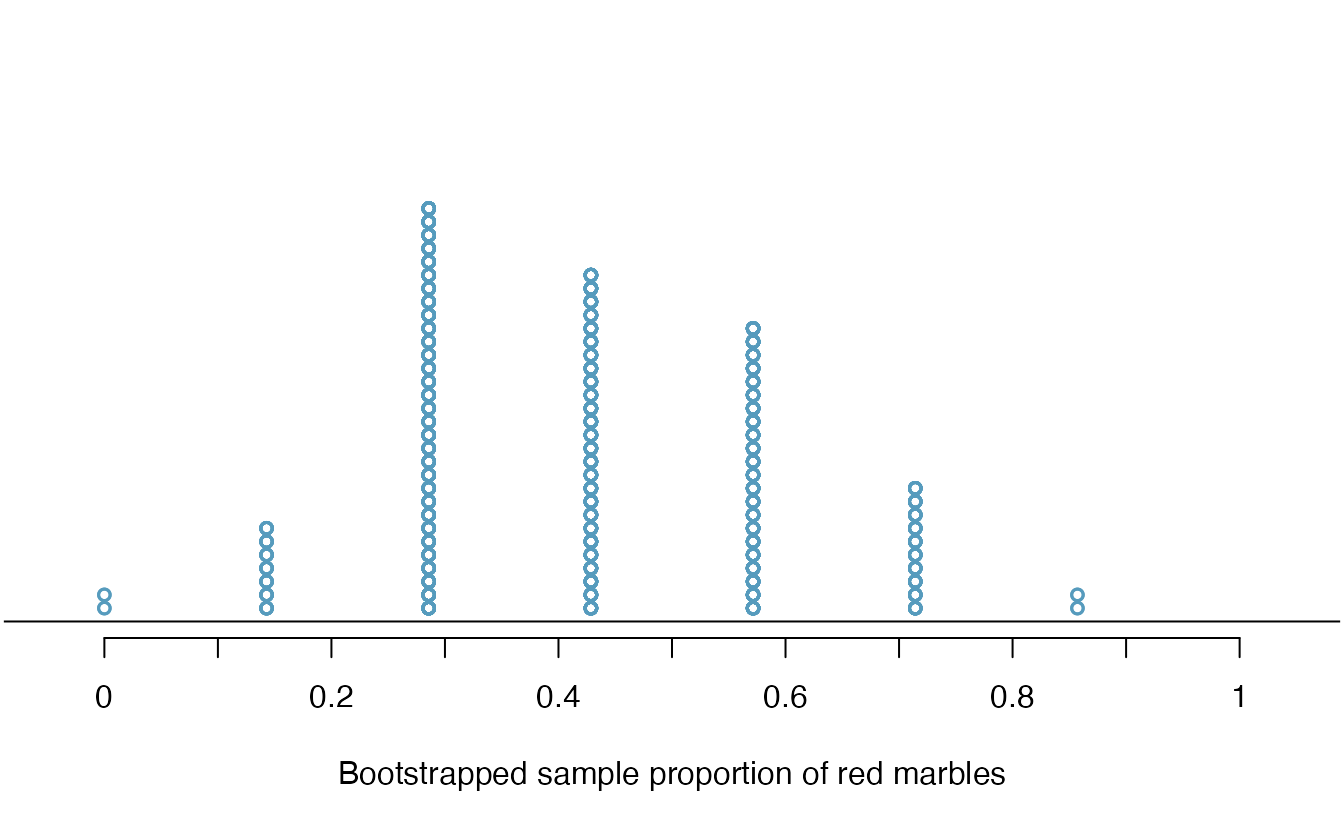

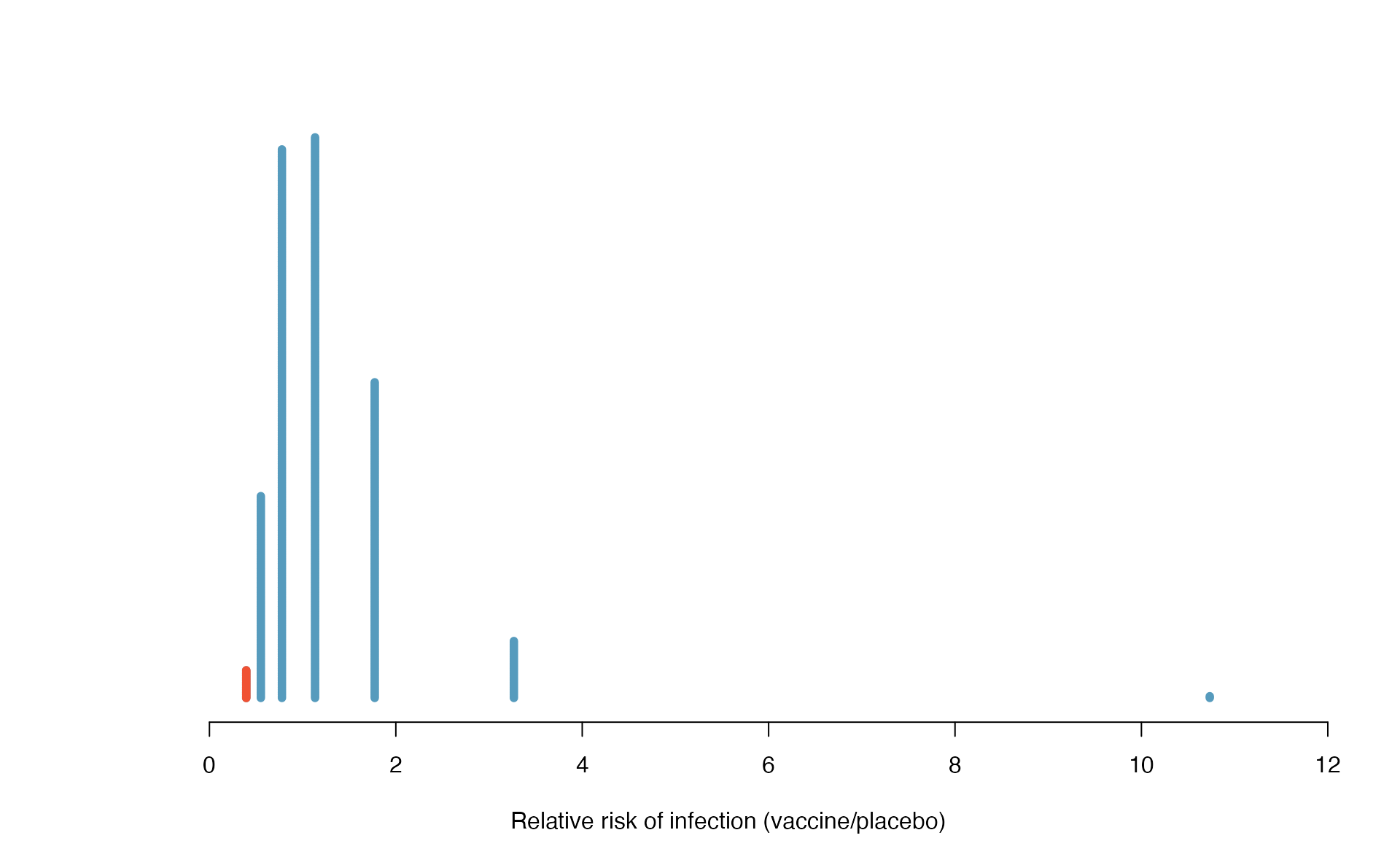

By summarizing each of the bootstrap samples (here, using the sample proportion), we see, directly, the variability of the sample proportion of red marbles, \(\hat{p}\), from sample to sample. The distribution of bootstrapped \(\hat{p}\)’s for the example scenario is shown in Figure 5.15, and the bootstrap distribution for the medical consultant data is shown in Figure 5.16.

Figure 5.15: Calculate the sample proportion of red marbles in each bootstrap resample, then plot these simulated sample proportions in a dot plot. The dot plot of sample proportion provides us a sense of how sample proportions would vary from sample to sample if we could take many samples from our original population.

It turns out that in practice, it is very difficult for computers to work with an infinite population (with the same proportional breakdown as in the sample). However, there is a physical and computational model which produces an equivalent bootstrap distribution of the sample proportion in a computationally efficient manner. Consider the observed data to be a bag of marbles 3 of which are red and 4 of which are white. By drawing the marbles out of the bag with replacement, we depict the same sampling process as was done with the infinitely large estimated population. Note that when sampling the original observations with replacement, a particular marble may end up in the new sample one time, multiple times, or not at all.

Bootstrapping from one sample.

- Take a random sample of size \(n\) from the original sample, with replacement. This is called a bootstrapped resample.

- Record the sample proportion (or statistic of interest) from the bootstrapped resample. This is called a bootstrapped statistic.

- Repeat steps (1) and (2) 1000s of times to create a distribution of bootstrapped statistics.

If we apply the bootstrap sampling process to the medical consultant example, we consider each client to be one of the marbles in the bag. There will be 59 white marbles (no complication) and 3 red marbles (complication). If we choose 62 marbles out of the bag (one at a time), replacing each chosen marble after its color is recorded, and compute the proportion of simulated patients with complications, \(\hat{p}_{bs}\), then this “bootstrap” proportion represents a single simulated proportion from the “resample from the sample” approach.

In a simulation of 62 patients conducted by sampling with replacement from the original sample, about how many would we expect to have had a complication?115

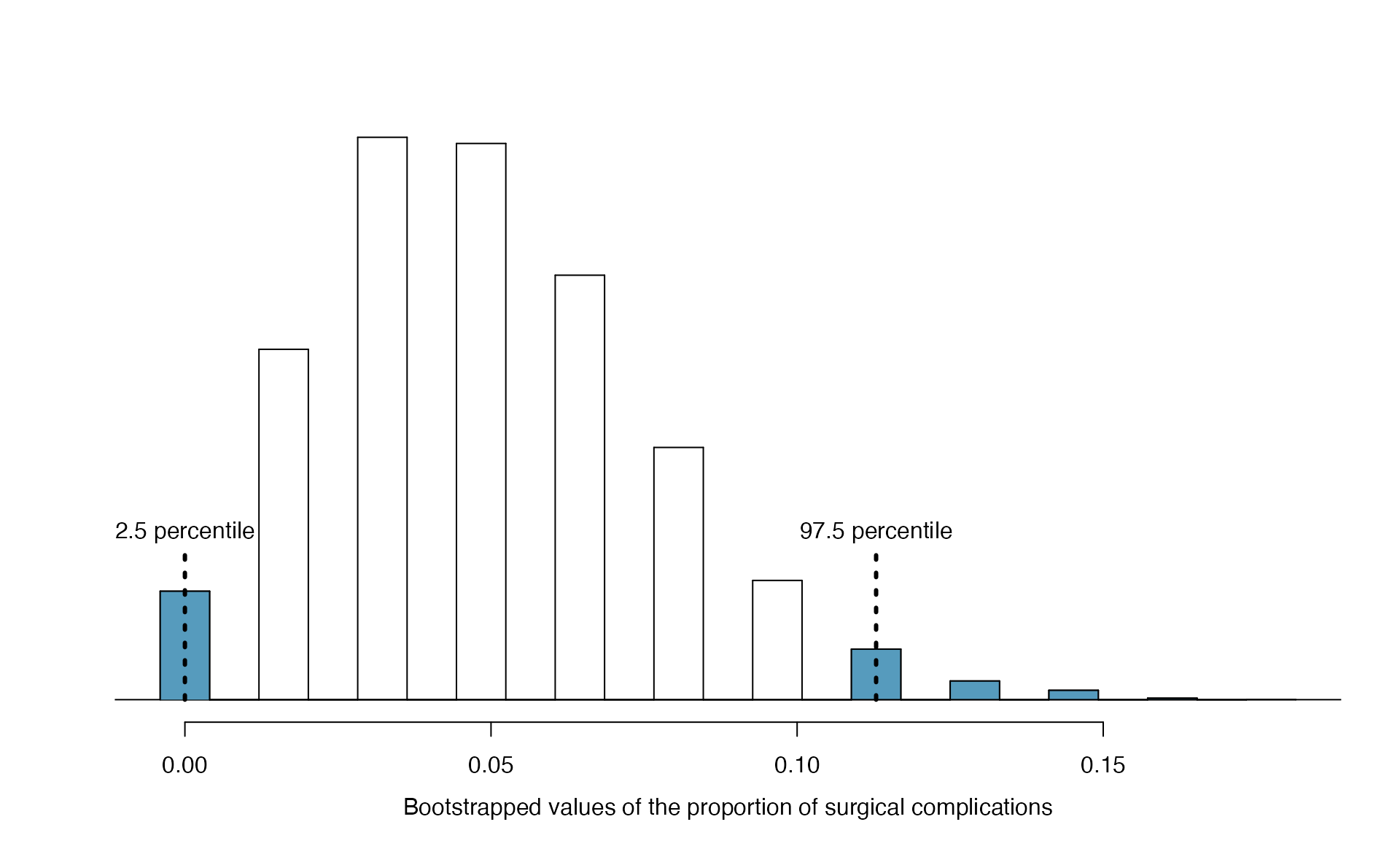

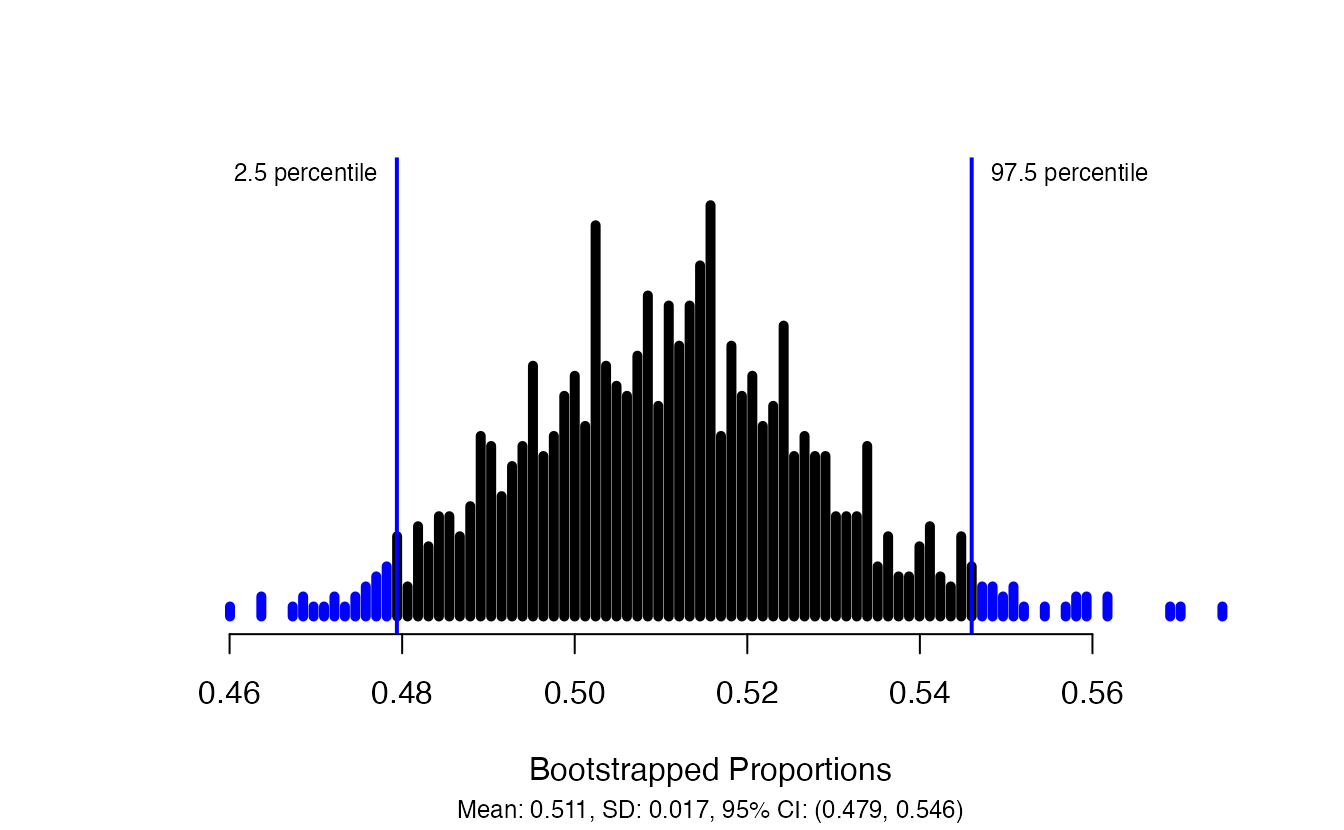

One simulated bootstrap resample isn’t enough to get a sense of the variability from one bootstrap proportion to another bootstrap proportion, so we repeated the simulation 10,000 times using a computer. Figure 5.16 shows the distribution from the 10,000 bootstrap simulations. The bootstrapped proportions vary from about zero to 0.15. By taking the range of the middle 95% of this distribution, we can construct a 95% bootstrapped confidence interval for \(\pi\). The 2.5th percentile is 0, and the 97.5th percentile is 0.113, so the middle 95% of the distribution is the range (0, 0.113). The variability in the bootstrapped proportions leads us to believe that the true risk of complication (the parameter, \(\pi\)) is somewhere between 0 and 11.3%.

Figure 5.16: The original medical consultant data is bootstrapped 10,000 times. Each simulation creates a sample from the original data where the probability of a complication is \(\hat{p} = 3/62\). The bootstrap 2.5 percentile proportion is 0 and the 97.5 percentile is 0.113. The result is: we are confident that, in the population, the true probability of a complication is between 0% and 11.3%.

95% Bootstrap confidence interval for a population proportion \(\pi\).

The 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the parameter \(\pi\) can be obtained directly using the ordered values \(\hat{p}_{boot}\) values — the bootstrapped sample proportions. Consider the sorted \(\hat{p}_{boot}\) values, and let \(\hat{p}_{boot, 0.025}\) be the 2.5th percentile value and \(\hat{p}_{boot, 0.975}\) be the 97.5th percentile. The 95% confidence interval is given by:

You can find confidence intervals of difference confidence levels by changing the percent of the distribution you take, e.g., locate the middle 90% of the bootstrapped statistics for a 90% confidence interval.

To find the middle 90% of a distribution, which two percentiles would form its boundaries?116

The original claim was that the consultant’s true rate of complication was under the national rate of 10%. Does the interval estimate of 0 to 11.3% for the true probability of complication indicate that the surgical consultant has a lower rate of complications than the national average? Explain.

No. Because the interval overlaps 10%, it might be that the consultant’s work is associated with a lower risk of complciations, or it might be that the consulant’s work is associated with a higher risk (i.e., greater than 10%) of complications! Additionally, as previously mentioned, because this is an observational study, even if an association can be measured, there is no evidence that the consultant’s work is the cause of the complication rate (being higher or lower).

5.3.4 Theory-based inferential methods for \(\pi\)

In Section 5.1.2, we introduced the normal distribution and showed how it can be used as a mathematical model to describe the variability of a sample mean or sample proportion as a result of the Central Limit Theorem. We explored the normal distribution further in Section 5.2. Theory-based hypothesis tests and confidence intervals for proportions use the normal distribution to calculate the p-value and to determine the width of the confidence interval.

Central Limit Theorem for the sample proportion.

When we collect a sufficiently large sample of \(n\) independent observations of a categorical variable from a population with \(\pi\) proportion of successes, the sampling distribution of \(\hat{p}\) will be nearly normal with \[\begin{align*} &\text{Mean}=\pi &&\text{Standard Deviation }(SD) = \sqrt{\frac{\pi(1-\pi)}{n}} \end{align*}\]

Evaluating the two conditions required for modeling \(\hat{p}\) using theory-based methods

There are two conditions required to apply the Central Limit Theorem for a sample proportion \(\hat{p}\). When the sample observations are independent and the sample size is sufficiently large, the normal model will describe the variability in sample proportions quite well; when the observations violate the conditions, the normal model can be inaccurate.

Conditions for the sampling distribution of \(\hat{p}\) to be approximately normal.

The sampling distribution for \(\hat{p}\) based on a sample of size \(n\) from a population with a true proportion \(\pi\) can be modeled using a normal distribution when:

Independence. The sample observations are independent, i.e., the outcome of one observation does not influence the outcome of another. This condition is met if data come from a simple random sample of the target population.

Success-failure condition. We expected to see at least 10 successes and 10 failures in the sample, i.e., \(n\pi\geq10\) and \(n(1-\pi)\geq10\). This condition is met if we have at least 10 successes and 10 failures in the observed data.

When these conditions are satisfied, then the sampling distribution of \(\hat{p}\) is approximately normal with mean \(\pi\) and standard deviation \(\sqrt{\frac{\ \pi(1-\pi)\ }{n}}\).

The success-failure condition listed above is only necessary for the sampling distribution of \(\hat{p}\) to be approximately normal. The mean of the sampling distribution of \(\hat{p}\) is \(\pi\), and the standard deviation is \(\sqrt{\frac{\ \pi(1-\pi)\ }{n}}\), regardless of the sample size.

Typically we don’t know the true proportion \(\pi\), so we substitute some value to check the success-failure condition and to estimate the standard deviation of the sampling distribution of \(\hat{p}\). The independence condition is a more nuanced requirement. When it isn’t met, it is important to understand how and why it isn’t met. For example, there exist no statistical methods available to truly correct the inherent biases of data from a convenience sample. On the other hand, if we took a cluster random sample (see Section 1.3.4), the observations wouldn’t be independent, but suitable statistical methods are available for analyzing the data (but they are beyond the scope of even most second or third courses in statistics)117.

In the examples based on large sample theory, we modeled \(\hat{p}\) using the normal distribution. Why is this not appropriate for the study on the medical consultant?

The independence assumption may be reasonable if each of the surgeries is from a different surgical team. However, the success-failure condition is not satisfied. Under the null hypothesis, we would anticipate seeing \(62\times 0.10=6.2\) complications, not the 10 required for the normal approximation.

Since theory-based methods cannot be used on the medical consultant example, we’ll turn to another example to demonstrate these methods, where conditions for approximating the distribution of \(\hat{p}\) by a normal distribution are met.

5.3.4.1 Hypothesis test for \(H_0: \pi = \pi_0\)

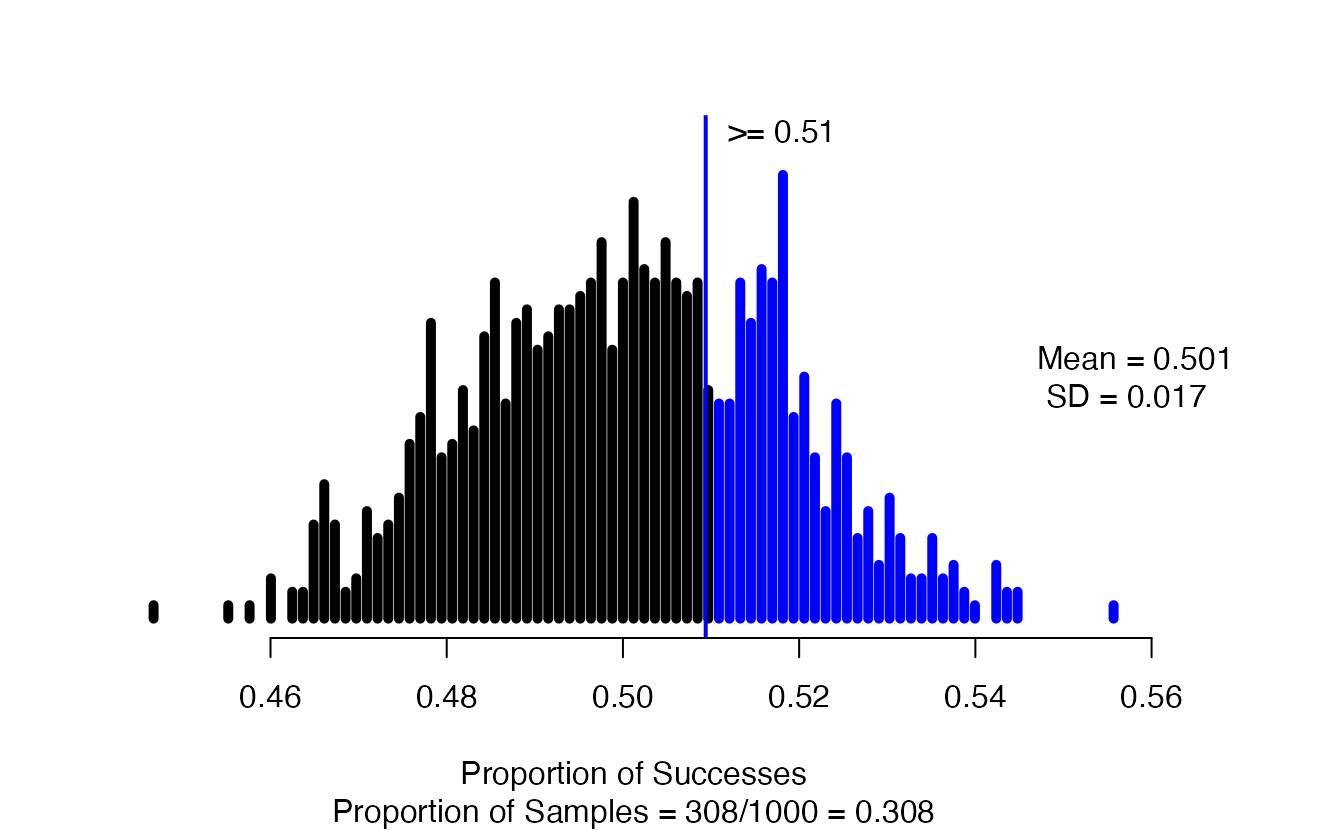

One possible regulation for payday lenders is that they would be required to do a credit check and evaluate debt payments against the borrower’s finances. We would like to know: would borrowers support this form of regulation?

Set up hypotheses to evaluate whether borrowers have a majority support for this type of regulation. We take “majority” to mean greater than 50% of the population.

In words,

- \(H_0\): there is not majority support for the regulation

- \(H_A\): the majority of borrowers support the regulation

In statistical notation,

- \(H_0\): \(\pi = 0.50\)

- \(H_A\): \(\pi > 0.50\),

where \(\pi\) represents the proportion of all payday loan borrowers that would support the regulation.

Note that the null hypothesis above was stated as \(H_0: \pi = 0.50\), even though saying there is “not majority support” would imply \(\pi \leq 0.50\). Indeed, some textbooks would write \(H_0: \pi \leq 0.50\) in this case, and it is not an incorrect statement. However, when calculating the p-value, we need to assume a particular value for \(\pi\) under the null hypothesis, so in this textbook, our null hypothesis will always be of the form:

\[ H_0: \mbox{ parameter } = \mbox{ null value} \]

To apply the normal distribution to model the null distribution, the independence and success-failure conditions must be satisfied. In a hypothesis test, the success-failure condition is checked using the null proportion: we verify \(n\pi_0\) and \(n(1-\pi_0)\) are at least 10, where \(\pi_0\) is the null value.

Do payday loan borrowers support a regulation that would require lenders to pull their credit report and evaluate their debt payments? From a random sample of 826 borrowers, 51% said they would support such a regulation. Is it reasonable use a normal distribution to model \(\hat{p}\) for a hypothesis test here?118

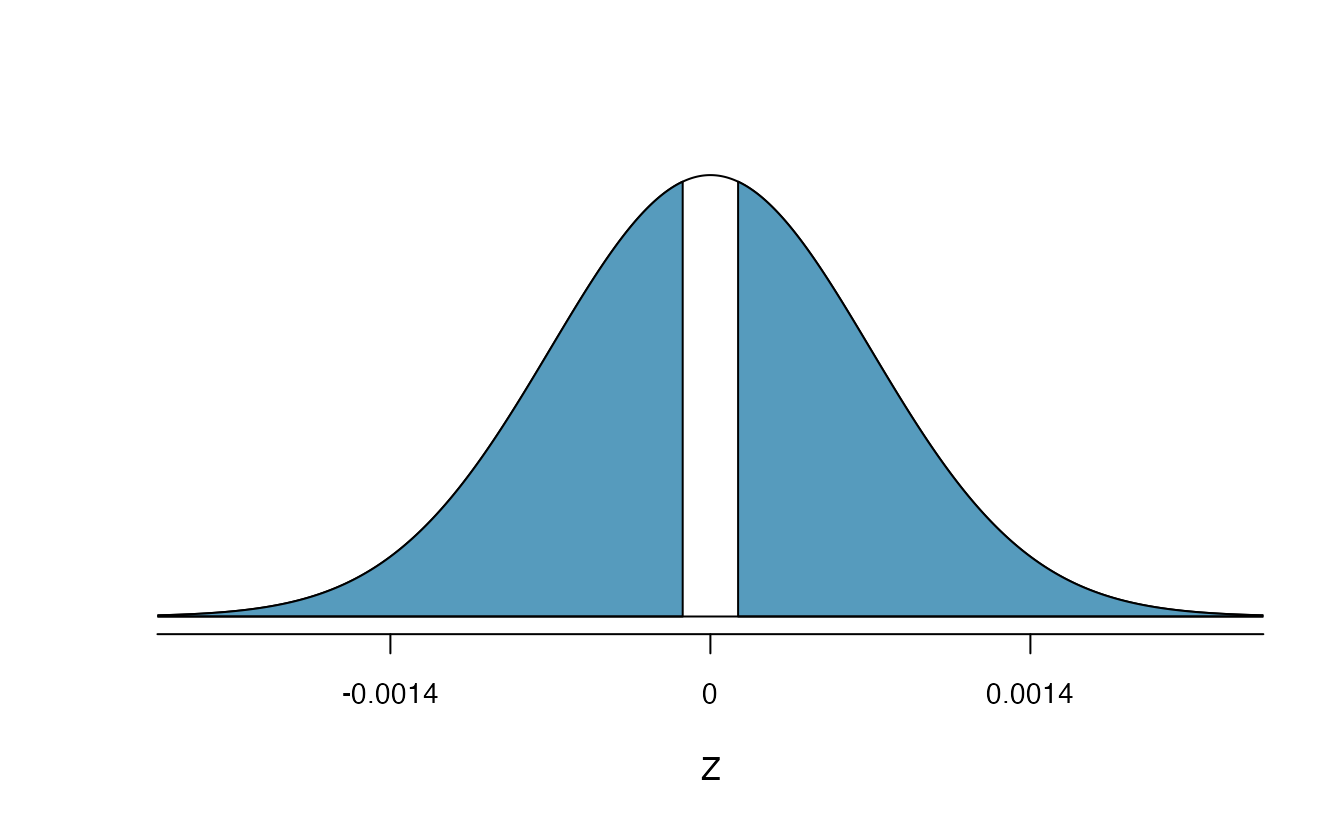

Continuing the previous Example, evaluate whether the poll on lending regulations provides convincing evidence that a majority of payday loan borrowers support a new regulation that would require lenders to pull credit reports and evaluate debt payments.

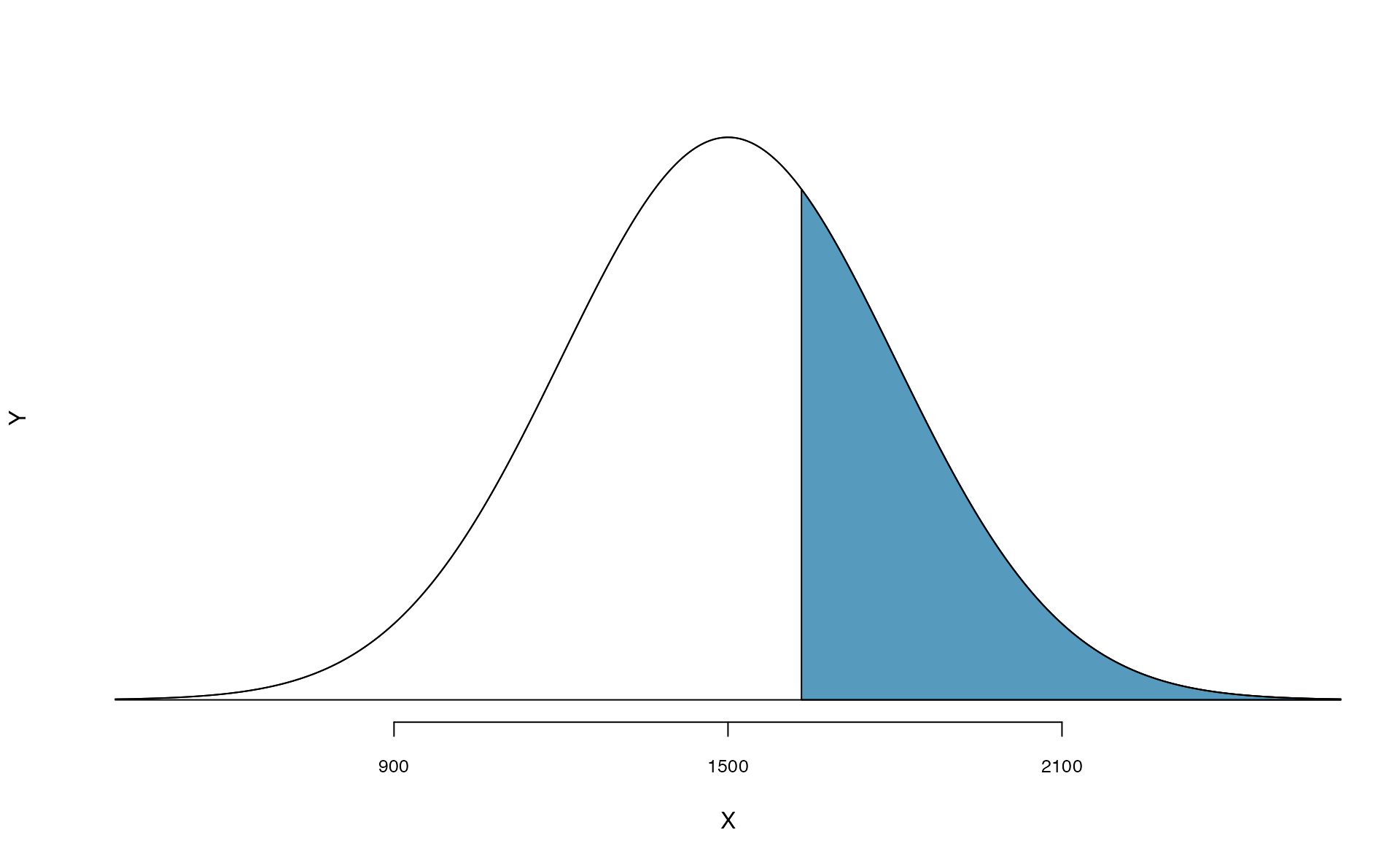

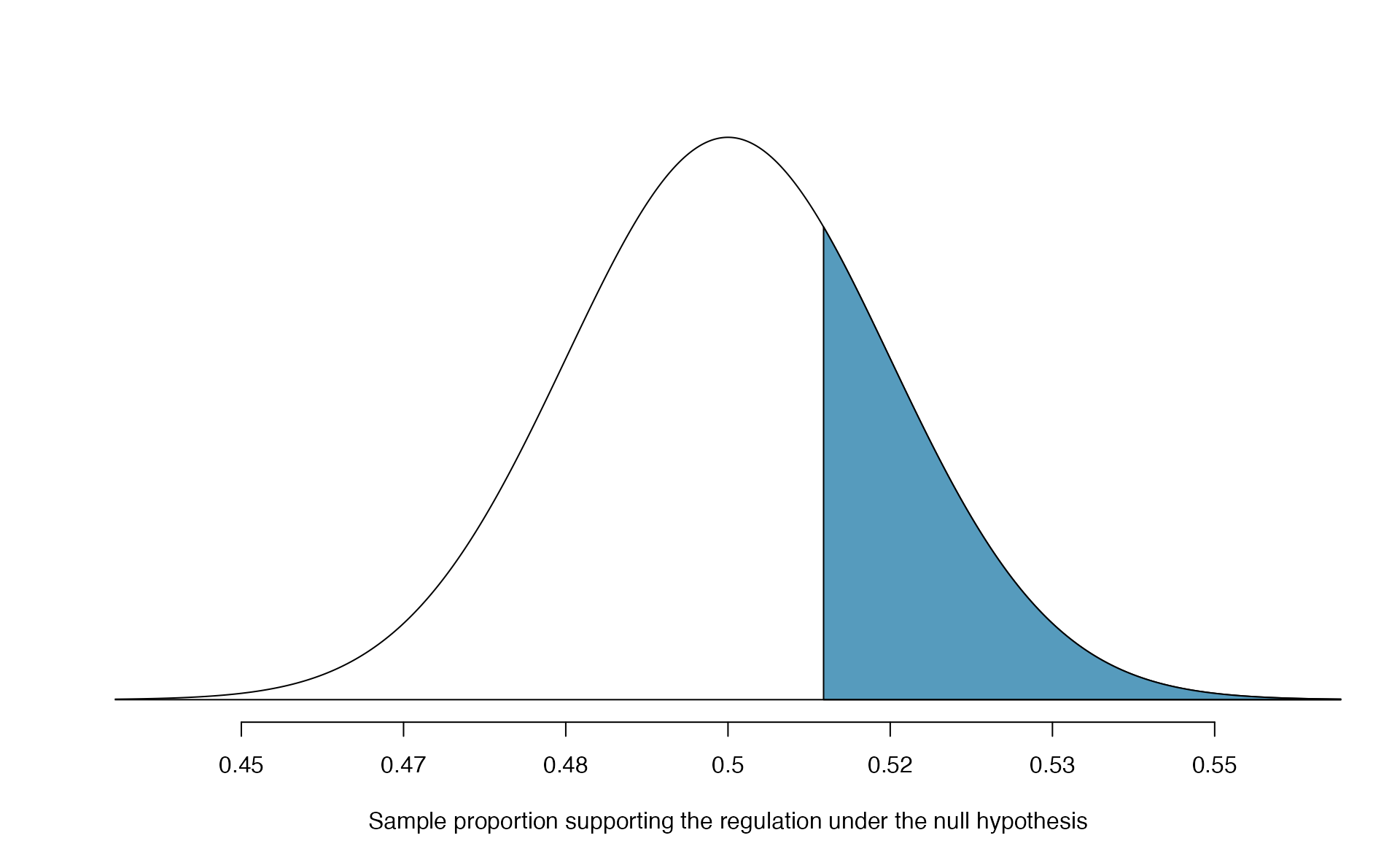

With hypotheses already set up and conditions checked, we can move onto calculations. The null standard error in the context of a one proportion hypothesis test is computed using the null value, \(\pi_0\): \[\begin{align*} SE_0(\hat{p}) = \sqrt{\frac{\pi_0 (1 - \pi_0)}{n}} = \sqrt{\frac{0.5 (1 - 0.5)}{826}} = 0.017 \end{align*}\] A picture of the normal model for the null distribution of sample proportions in this scenario is shown below in Figure 5.17, with the p-value represented by the shaded region. Note that this null distribution is centered at 0.50, the null value, and has standard deviation 0.017.

Under \(H_0\), the probability of observing \(\hat{p} = 0.51\) or higher is 0.278, the area above 0.51 on the null distribution.

With a p-value of 0.278, the poll does not provide convincing evidence that a majority of payday loan borrowers support regulations around credit checks and evaluation of debt payments.

You’ll note that this conclusion is somewhat unsatisfactory because there is no conclusion, as is the case with larger p-values. That is, there is no resolution one way or the other about public opinion. We cannot claim that exactly 50% of people support the regulation, but we cannot claim a majority support it either.

Figure 5.17: Approximate sampling distribution of \(\hat{p}\) across all possible samples assuming \(\pi = 0.50\). The shaded area represents the p-value corresponding to an observed sample proportion of 0.51.

Often, with theory-based methods, we use a standardized statistic rather than the original statistic as our test statistic. A standardized statistic is computed by subtracting the mean of the null distribution from the original statistic, then dividing by the standard error: \[ \mbox{standardized statistic} = \frac{\mbox{observed statistic} - \mbox{null value}}{\mbox{null standard error}} \] The null standard error (\(SE_0(\text{statistic})\)) of the observed statistic is its estimated standard deviation assuming the null hypothesis is true. We can interpret the standardized statistic as the number of standard errors our observed statistic is above (if positive) or below (if negative) the null value. When we are modeling the null distribution with a normal distribution, this standardized statistic is called \(Z\), since it is the Z-score of the sample proportion.

Standardized sample proportion.

The standardized statistic for theory-based methods for one proportion is \[ Z = \frac{\hat{p} - \pi_0}{\sqrt{\frac{\pi_0(1-\pi_0)}{n}}} = \frac{\hat{p} - \pi_0}{SE_0(\hat{p})} \] where \(\pi_0\) is the null value. The denominator, \(SE_0(\hat{p}) = \sqrt{\frac{\pi_0(1-\pi_0)}{n}}\), is called the null standard error of the sample proportion.

With the standardized statistic as our test statistic, we can find the p-value as the area under a standard normal distribution at or more extreme than our observed \(Z\) value.

Do payday loan borrowers support a regulation that would require lenders to pull their credit report and evaluate their debt payments? From a random sample of 826 borrowers, 51% said they would support such a regulation. We set up hypotheses and checked conditions previously. Now calculate and interpret the standardized statistic, then use the standard normal distribution to calculate the approximate p-value.

Our sample proportion is \(\hat{p} = 0.51\). Since our null value is \(\pi_0 = 0.50\),

the null standard error is \[\begin{align*}

SE_0(\hat{p}) = \sqrt{\frac{\pi_0 (1 - \pi_0)}{n}}

= \sqrt{\frac{0.5 (1 - 0.5)}{826}}

= 0.017

\end{align*}\]

The standardized statistic is \[\begin{align*} Z = \frac{0.51 - 0.50}{0.017} = 0.59 \end{align*}\]

Interpreting this value, we can say that our sample proportion of 0.51 was only 0.59 standard errors above the null value of 0.50.

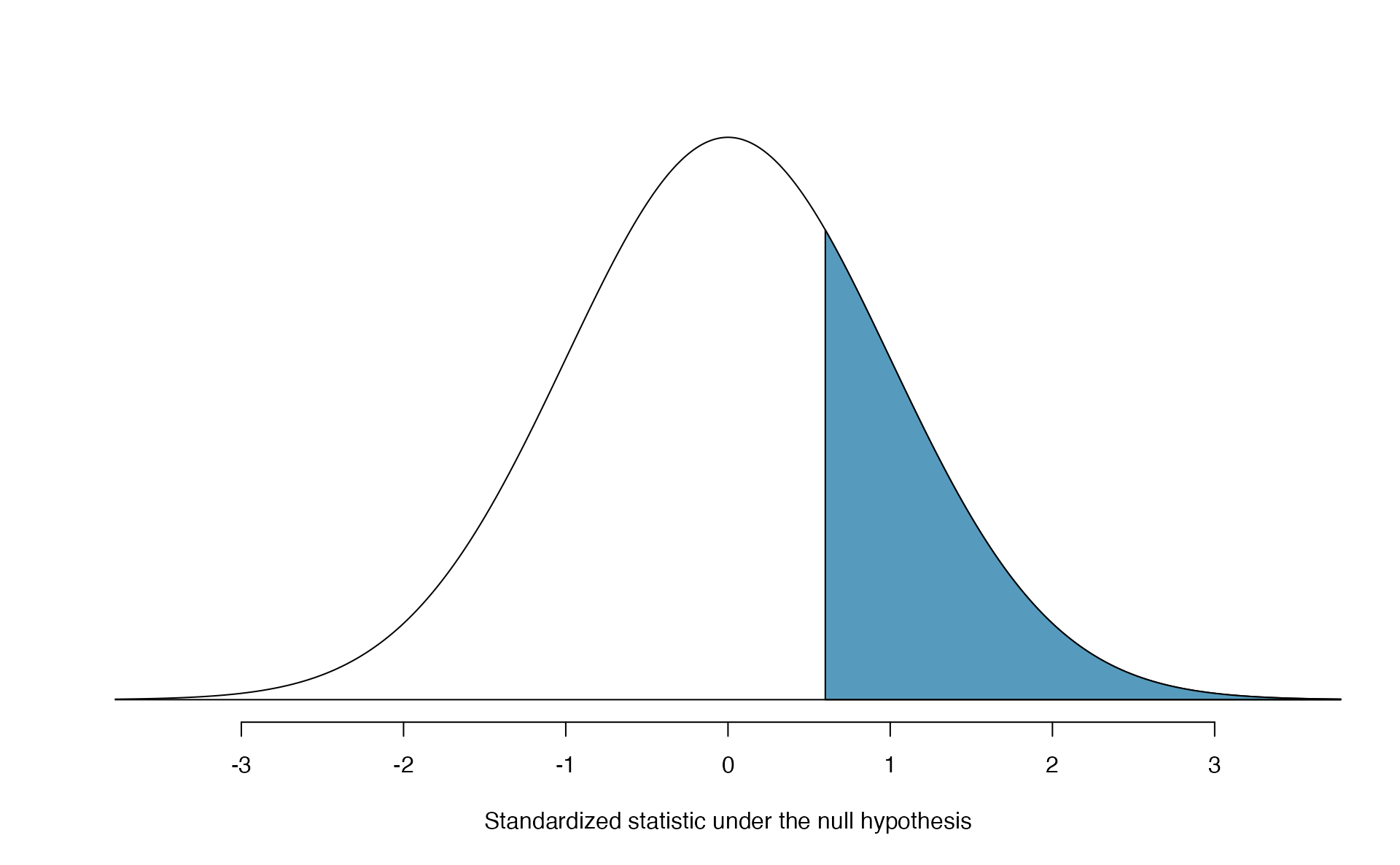

Shown in Figure 5.18, the p-value is the area above \(Z = 0.59\) on a standard normal distribution—0.278—the same p-value we would obtain by finding the area above \(\hat{p} = 0.51\) on a normal distribution with mean 0.50 and standard deviation 0.017, as in Figure 5.17.

Figure 5.18: Approximate sampling distribution of \(Z\) across all possible samples assuming \(\pi = 0.50\). The shaded area represents the p-value corresponding to an observed standardized statistic of 0.59. Compare to Figure 5.17.

Theory-based hypothesis test for a proportion: one-sample \(Z\)-test.

- Frame the research question in terms of hypotheses.

- Using the null value, \(\pi_0\), verify the conditions for using the normal distribution to approximate the null distribution.

- Calculate the test statistic: \[ Z = \frac{\hat{p} - \pi_0}{\sqrt{\frac{\pi_0(1-\pi_0)}{n}}} = \frac{\hat{p} - \pi_0}{SE_0(\hat{p})} \]

- Use the test statistic and the standard normal distribution to calculate the p-value.

- Make a conclusion based on the p-value, and write a conclusion in context, in plain language, and in terms of the alternative hypothesis.

Regardless of the statistical method chosen, the p-value is always derived by analyzing the null distribution of the test statistic. The normal model poorly approximates the null distribution for \(\hat{p}\) when the success-failure condition is not satisfied. As a substitute, we can generate the null distribution using simulated sample proportions and use this distribution to compute the tail area, i.e., the p-value. Neither the p-value approximated by the normal distribution nor the simulated p-value are exact, because the normal distribution and simulated null distribution themselves are not exact, only a close approximation. An exact p-value can be generated using the binomial distribution, but that method will not be covered in this text.

Confidence interval for \(\pi\)

A confidence interval provides a range of plausible values for the parameter \(\pi\). A point estimate is our best guess for the value of the parameter, so it makes sense to build the confidence interval around that value. The standard error, which is a measure of the uncertainty associated with the point estimate, provides a guide for how large we should make the confidence interval. When \(\hat{p}\) can be modeled using a normal distribution, the 68-95-99.7 rule tells us that, in general, 95% of observations are within 2 standard errors of the mean. Here, we use the value 1.96 to be slightly more precise. The confidence interval for \(\pi\) then takes the form \[\begin{align*} \hat{p} \pm z^{\star} \times SE(\hat{p}). \end{align*}\]

We have seen \(\hat{p}\) to be the sample proportion. The value \(z^{\star}\) comes from a standard normal distribution and is determined by the chosen confidence level. The value of the standard error of \(\hat{p}\), \(SE(\hat{p})\), approximates how far we would expect the sample proportion to fall from \(\pi\), and depends heavily on the sample size.

Standard error of one proportion, \(\hat{p}\).

When the conditions are met so that the distribution for \(\hat{p}\) is nearly normal, the variability of a single proportion, \(\hat{p}\) is well described by its standard deviation:

\[SD(\hat{p}) = \sqrt{\frac{\pi(1-\pi)}{n}}\]

Note that we almost never know the true value of \(\pi\), but we can substitute our best guess of \(\pi\) to obtain an approximate standard deviation, called the standard error of \(\hat{p}\):

\[SD(\hat{p}) \approx \hspace{3mm} SE(\hat{p}) = \sqrt{\frac{(\mbox{best guess of }\pi)(1 - \mbox{best guess of }\pi)}{n}}\]

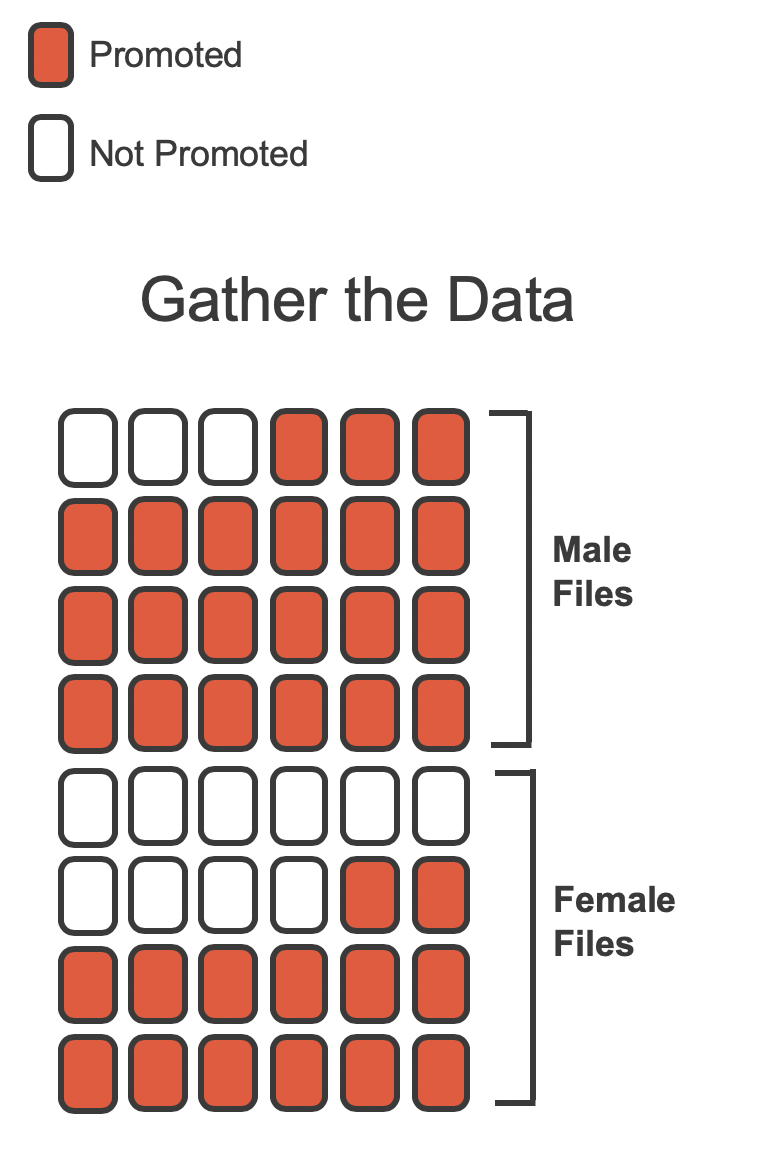

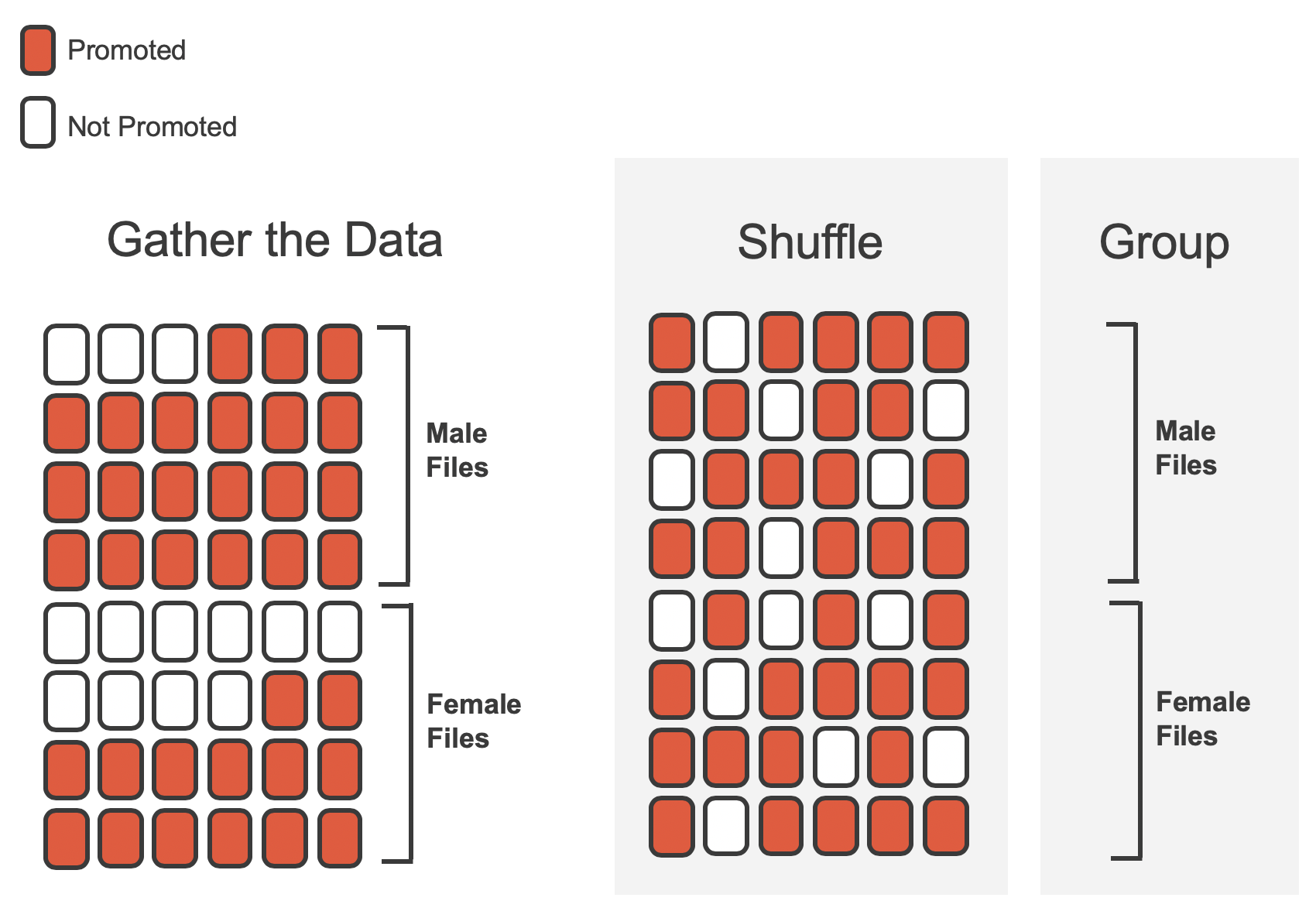

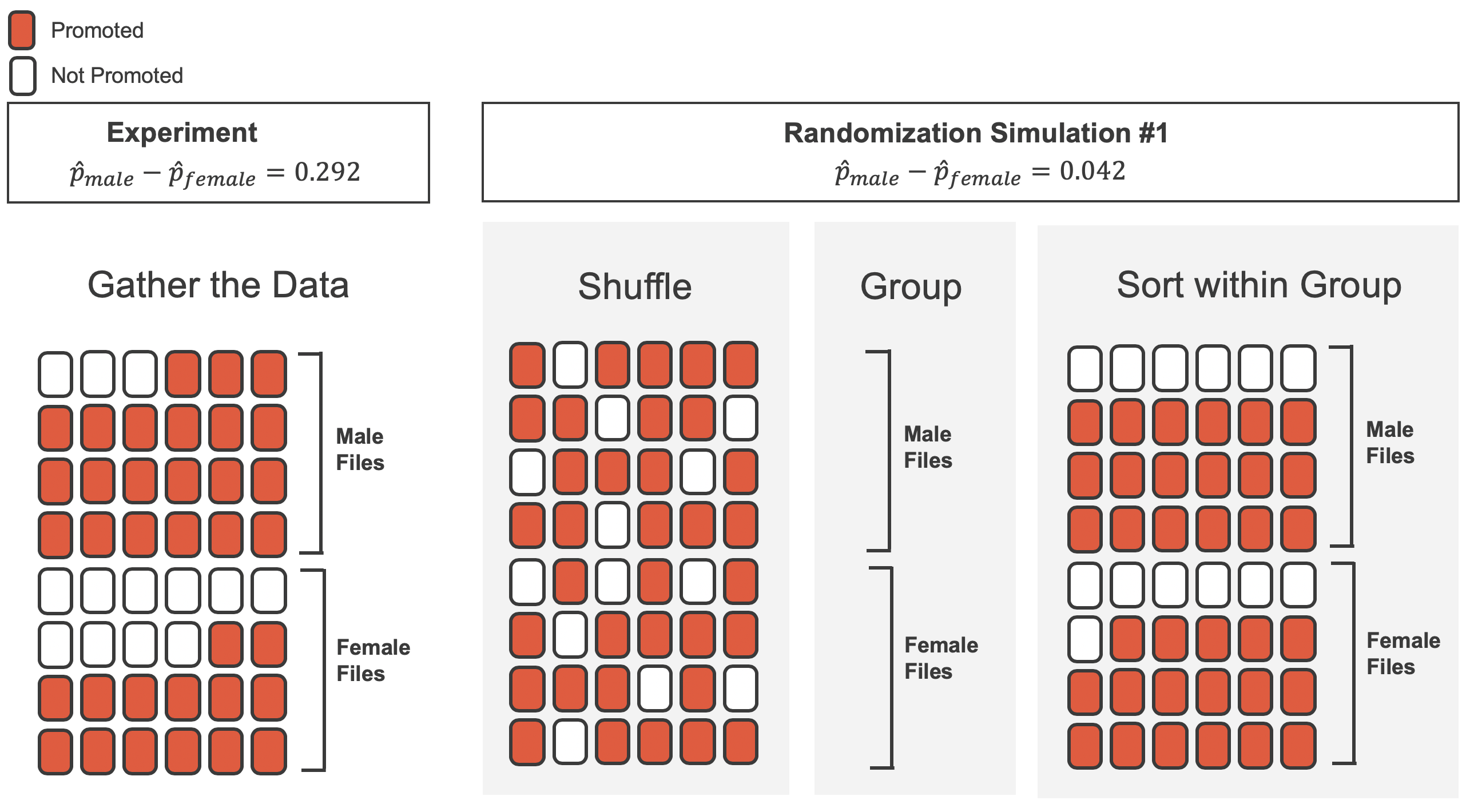

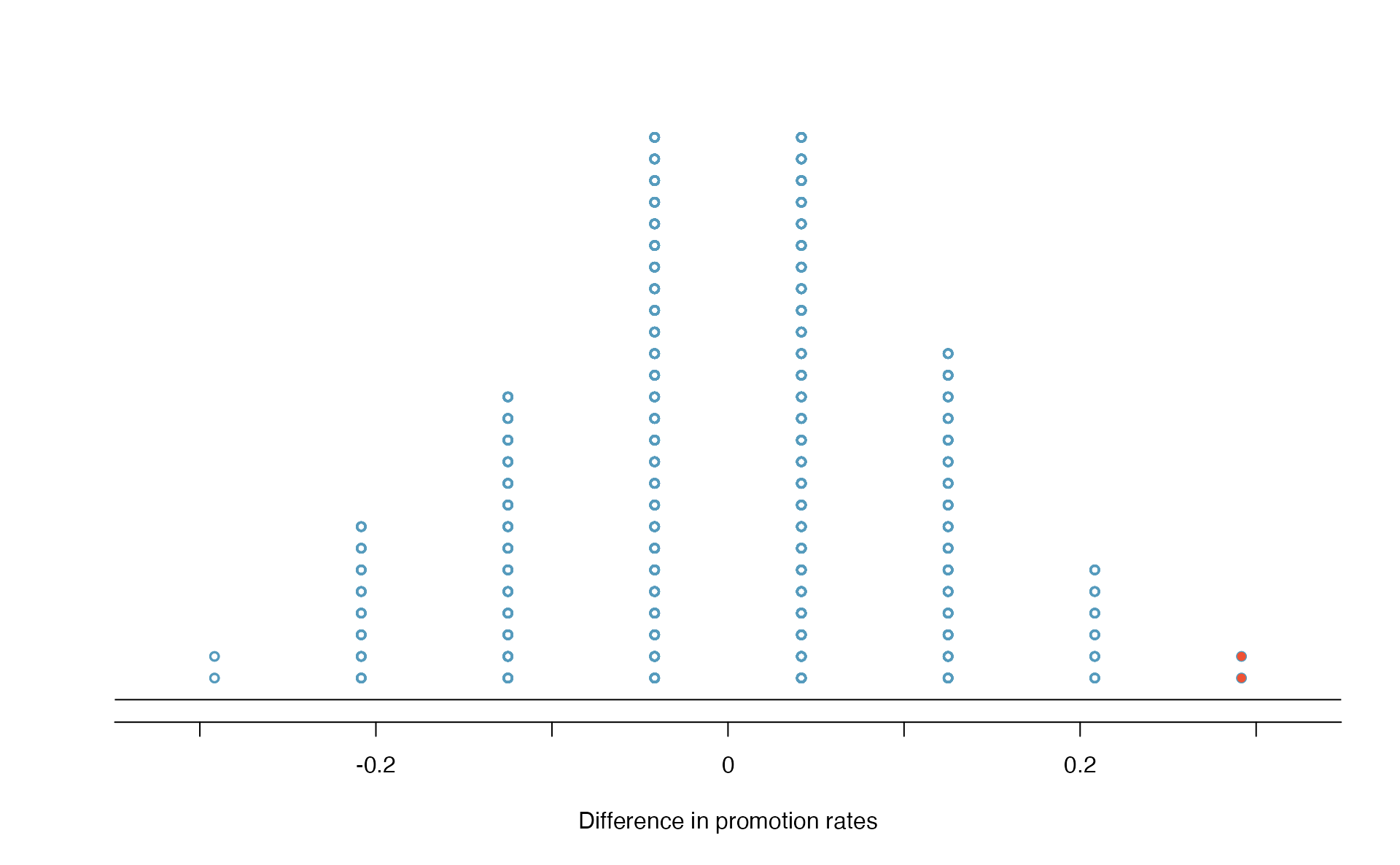

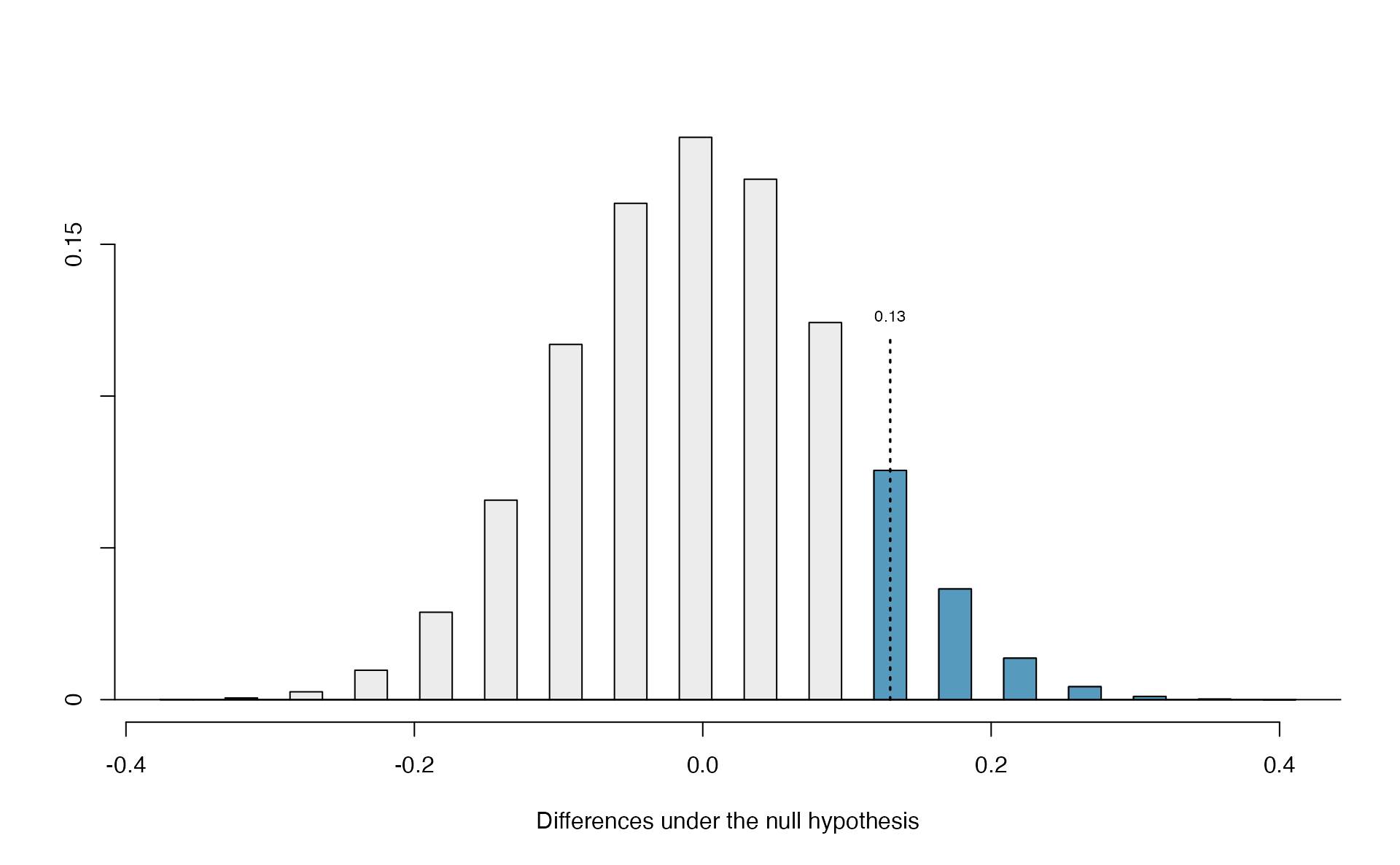

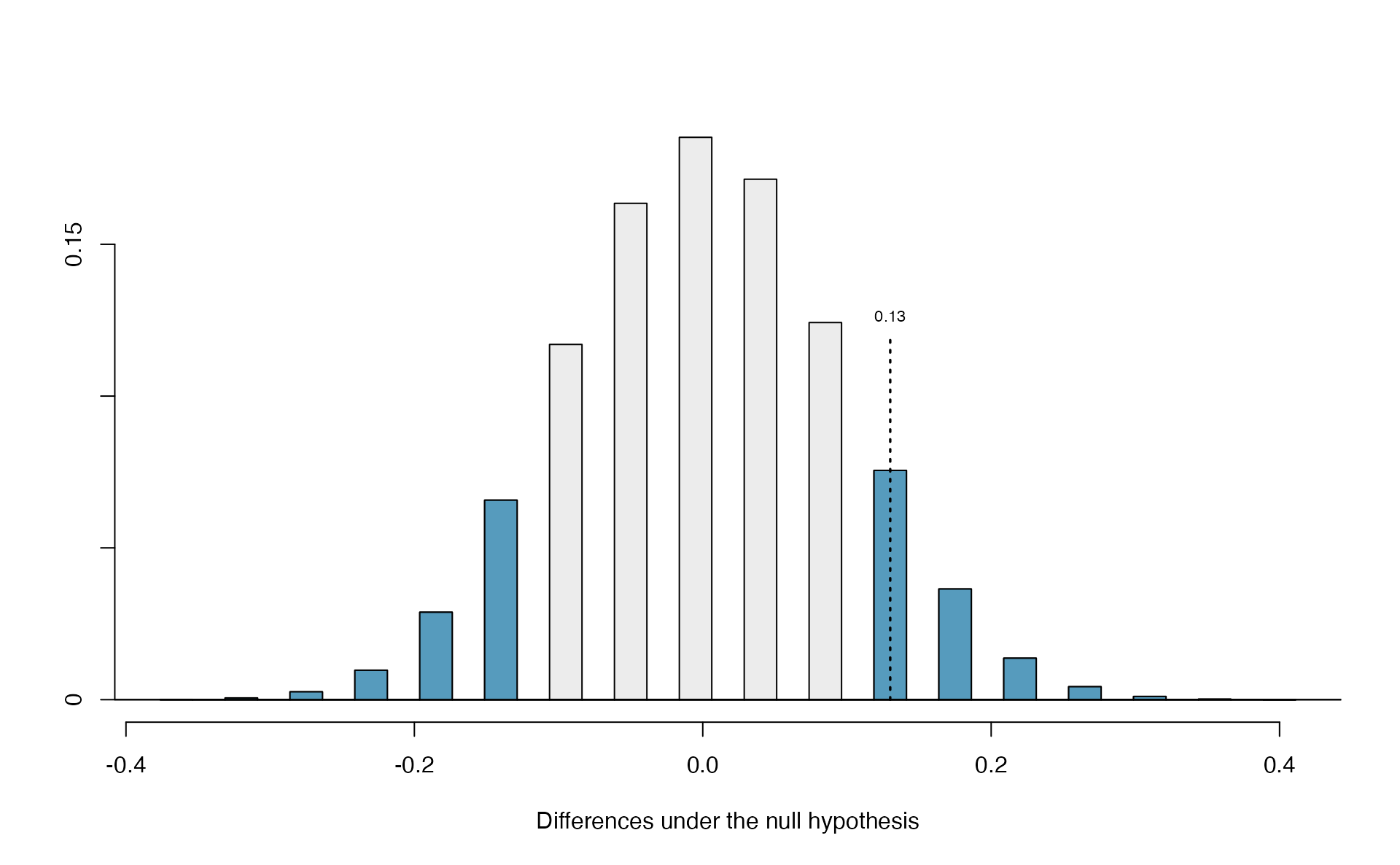

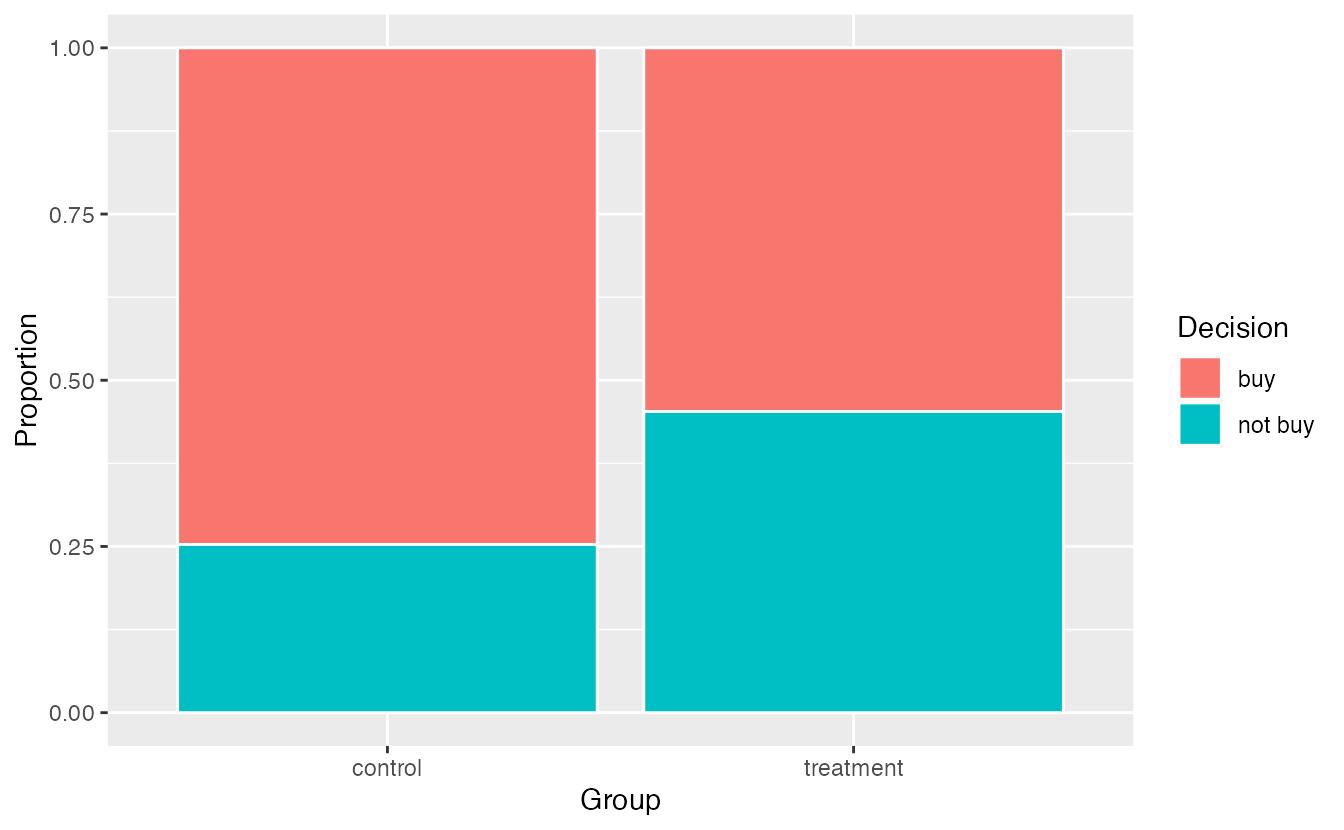

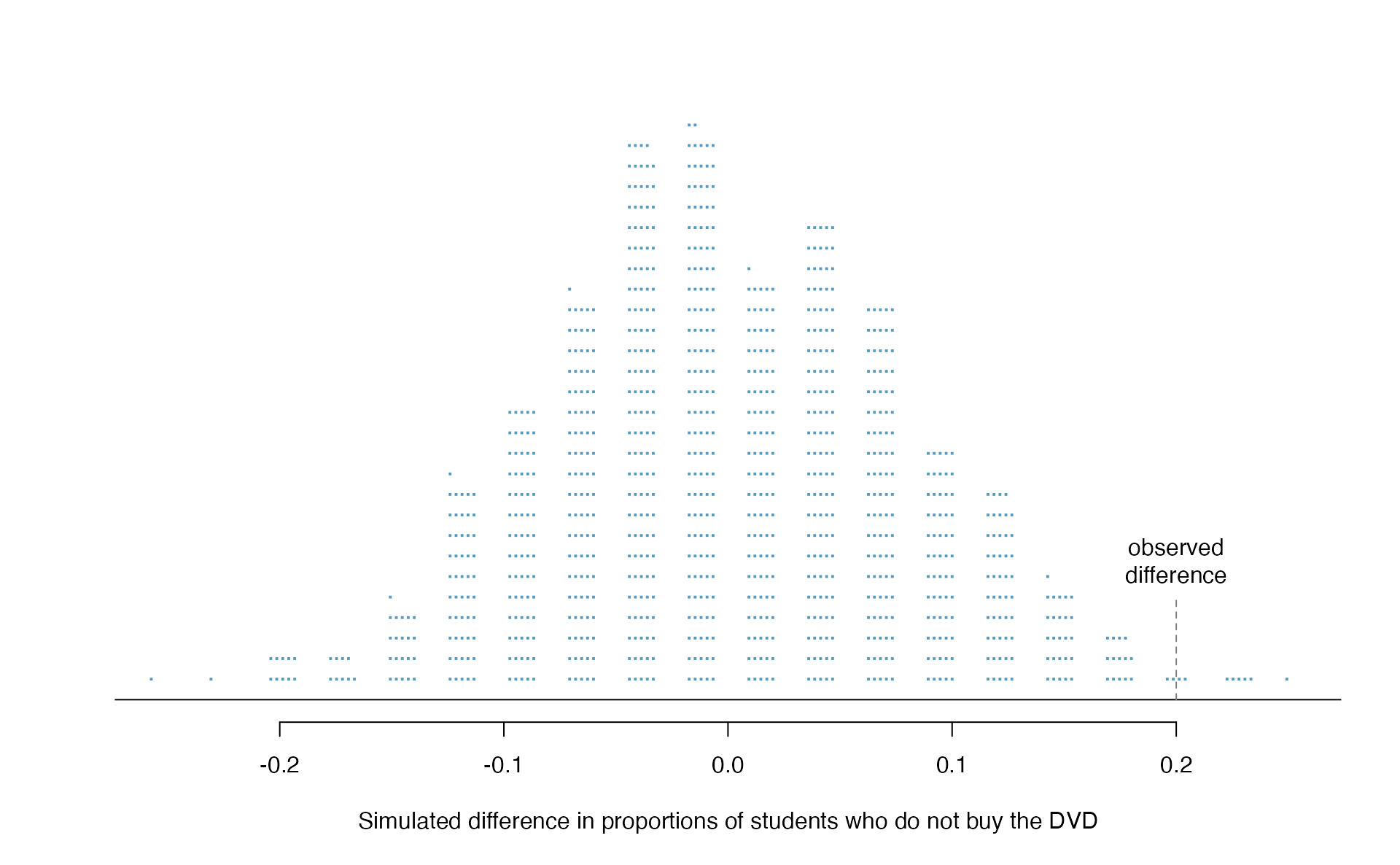

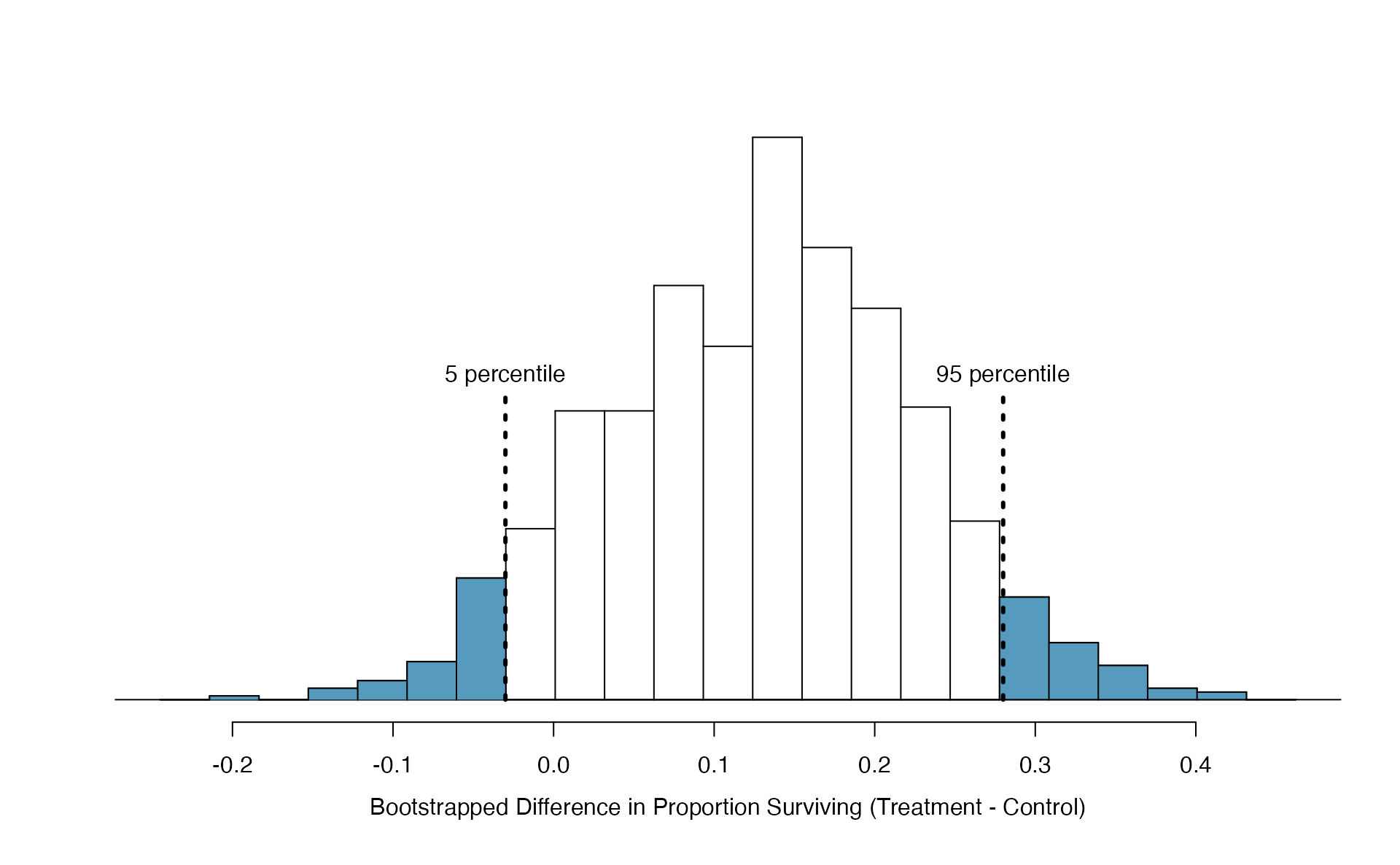

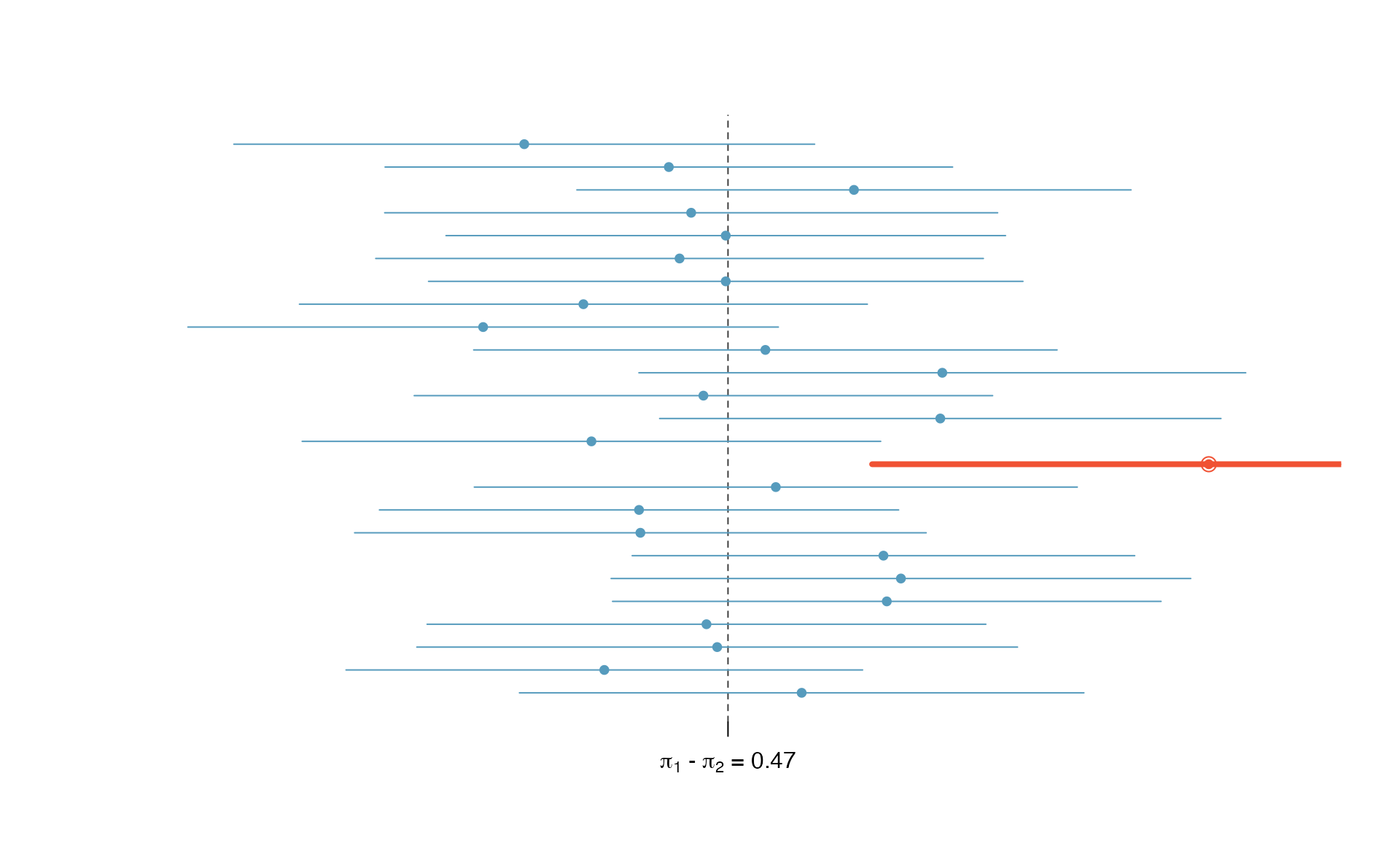

For hypothesis testing, we often use \(\pi_0\) as the best guess of \(\pi\), as seen in Section 5.3.4. For confidence intervals, we typically use \(\hat{p}\) as the best guess of \(\pi\).